Blogg

Här finns tekniska artiklar, presentationer och nyheter om arkitektur och systemutveckling. Håll dig uppdaterad, följ oss på Twitter

Här finns tekniska artiklar, presentationer och nyheter om arkitektur och systemutveckling. Håll dig uppdaterad, följ oss på Twitter

This blog is based on two questions (problems) and an example of how they can be solved using Mule ESB and the upcoming nio-http-transport.

Why does it have to be so hard to stream or push updates from a server to HTML based applications (mobile or not)?

Why does my ESB server go on its knees by having a large number of outstanding HTTP requests that it routed to backend systems, waiting for responses from slow backend system (to be sent back to the callers)?

The problem in question #1 comes from the communication protocol used between HTML clients and servers, HTTP. The HTTP protocol is only half-duplex so there is no natural way for a server to initiate the communication to push data to a client. Therefore all sorts of workarounds have been applied over the years including polling, long polling, piggybacking, Comet and Reverse AJAX (AJAX Push). They all introduce unnecessary complex and resource demanding solutions. Pushing, for example, data in real time (millisecond range, constrained by the network latency of course) to say 10 000 mobile HTML clients with meaning Used NNN just clicked on key ‘A’ on his keyboard is with this type of solutions challenging to say the least. This is however about to change…

The problem in question #2 comes from the historical way of handling synchronous communication, e.g. HTTP, in servers where each request is handled by a separate thread. Given an ESB server that mediates synchronous requests (e.g. authenticate, authorize, transform, route and log) to backend systems this is in the normal case not a major issue. But if the load goes up, e.g. to hundreds and thousands of concurrent requests and some of the backend systems start to respond slowly the one thread per request model can quickly drain the resources of the ESB server and make it behave slow and eventually crash, not so good at all. This is known as the concurrent ten thousand connections problem or for short the C10k problem. This is also about to change…

The solution to problem #1 is called WebSockets, described as Web Sockets are “TCP for the Web,” a next-generation bidirectional communication technology for web applications in the initial publication of WebSockets, done by Google back in December 2009. Nowadays WebSockets is a part of the HTML5 initiative and specifications are available at W3C (API) and IETF (protocol). As always, when it comes to new technologies, the platforms have to be adopted before large-scale use can be applied, in this case meaning the web browsers. Nowadays the support is widespread in the latest versions of the web browsers, see http://caniuse.com/websockets. But, of course, more time is needed before these new versions of the web browsers are installed in desktops and mobiles all over the world. On the server side a large number of implementations exists so that is not an issue any longer. Tons of blogs, articles and books have been written on this subject so I will not go into further details in this blog, instead I encourage the interested reader to google on the subject, recommending http://www.websocket.org/ and the DZone Refcard on WebSockets as good introductory material.

The solution to problem #2 is called non-blocking I/O, removing the legacy model of allocating one thread per synchronous request in a server, leading to orders of magnitude improved scalability. When it comes to Java this has been supported by the Java platform since Java SE v1.4 (released in February 2002) based on a set of API’s called New I/O (NIO). Over the years popular Java based web servers and frameworks for HTTP such as Jetty and Netty has evolved support for non-blocking I/O using the NIO-API in Java SE. So far, however, full-blown ESB’s (handling all types of protocols and mediation) has been lacking support for non-blocking I/O for HTTP traffic. This is again about to change…

On the QCon conference in San Francisco 2012 Ross Mason, founder and CTO of MuleSoft, did a presentation on the subject Going real-time: How to build a streaming API. Ross also made a demo on the subject available at GitHub, revealing a new, not yet released, transport in Mule ESB called nio-http-transport. The purpose of this transport is rather obvious, adding support for non-blocking I/O based on the Java SE NIO API. Looking into the details reveals that the new transport is based on Netty and also have support for WebSockets!

Based on a modified version of the code base in Ross demo I have setup a test case where a single Mule ESB server streams (or push if you prefer) in real time updates to >10 000 WebSocket-clients. To simulate the 10 000 clients I used a load-test program that performs 10 000 WebSocket connections and for each connection perform an initial send (subscribing to a topic of interest), receives messages and collects statistics of the received messages to verify that the test actually works.

I also wrote a HTML-WebSocket-client that makes the same as the load-test program but for only one connection at the time to verify that the test also works with HTML based applications.

Mule create one message per second and the payload pushed to the WebSocket clients is based on JSON and typically looks like:

{

"request" : 20,

"timestamp" : "23:10:33.010",

"connections" : 10001,

"identifier" : "1",

"elements" : "gjrlumqcuj"

}

Where:

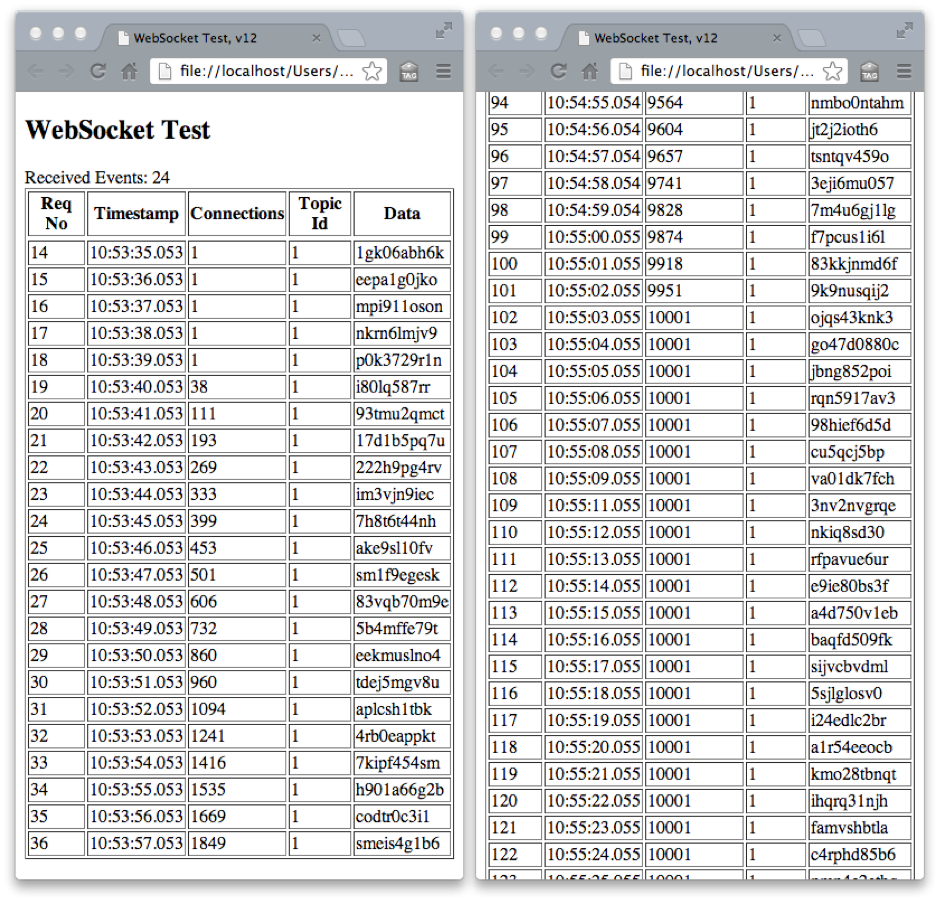

request the id of the payload-messagetimestamp when the message was created in the serverconnections the number of connected WebSockets clients in Mule at the time the message was createdidentifier the id on the topic for this message.elements some varying dataThe output from the HTML-client looks like:

From the screenshot above you can see an initial phase (first 100 messages, i.e. 100 secs) where all WebSocket clients perform their connections to Mule and after that a steady phase where Mule stream 10 000 messages per second to the WebSocket clients.

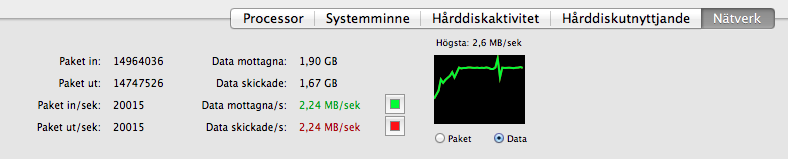

Even though each message is very small and the overhead in the WebSocket protocol is minimal 10 000 msg/sec still creates a substantial network traffic, a bit over 2 MB/s in my case: (sorry for the Swedish labels, I hope you still can recognize the network metrics )

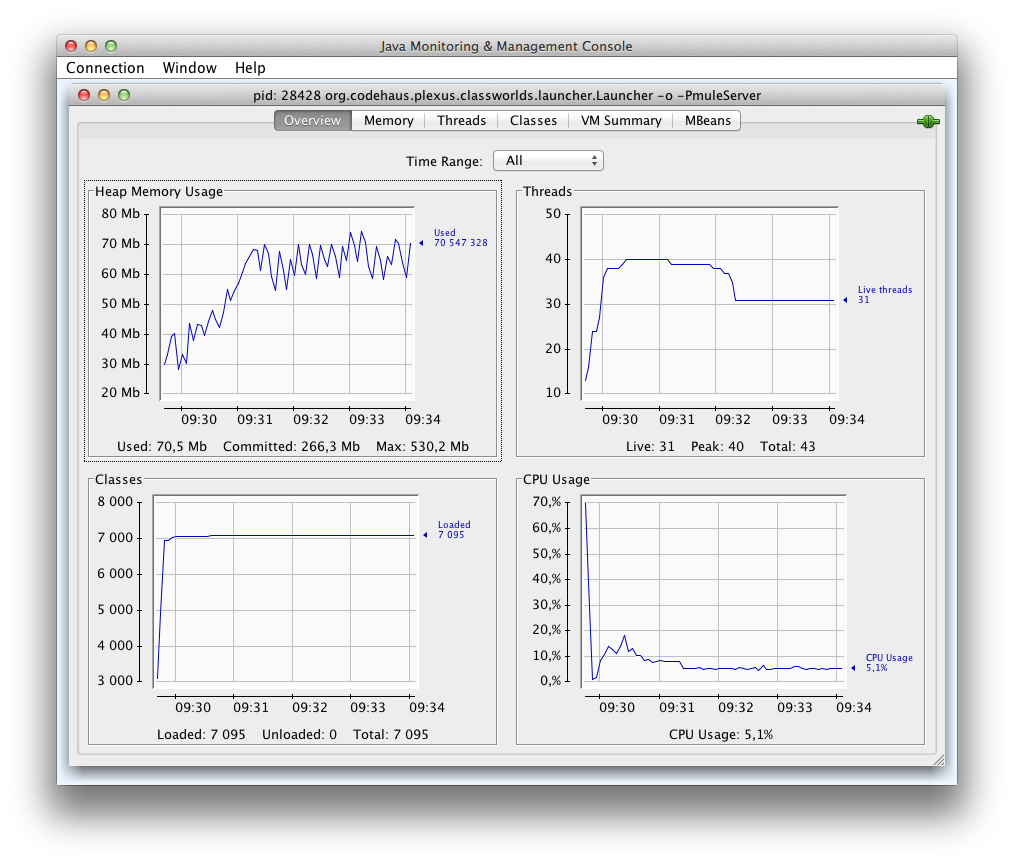

Resource usage by Mule ESB (memory, cpu and most important threads) was monitored using JConsole and the result from running this test looks like:

As can be seen in the screenshot the initial connect phase caused a bit higher usage of the cpu but after that initial phase both cpu usage and memory consumption is stabilized on a very moderate level.

But of most importance in this screenshot is the thread usage. After an initial peek of 40 threads the usage goes down to 31 threads in the steady state phase!

31 threads serving (among other work) 10 000 concurrent real time WebSocket clients!!!

C10k problem SOLVED!

Note #1: The cpu usage is of course to a large extent depending on the number of connected clients and the frequency of the messages pushed to the clients.

Note #2: To be able to handle 10 000 WebSocket clients in a single Mule instance the maximal number of open files had to be increased significantly in the operating system (OS X in my case).

I plan to publish the source code for these tests in the near future so that you can repeat them your self, but the code is currently a bit too messy in some parts to be published. But let’s take a look at some of the most important code constructs:

<flow name="websocket-flow">

<http:inbound-endpoint

address="niohttp://localhost:8080/websocket/events"

exchange-pattern="one-way">

<http:websocket path="events" />

</http:inbound-endpoint>

<custom-processor

class="com.mulesoft.demo.mule.websocket.ConnectionTracker"/>

</flow>

It looks very similar to a regular blocking HTTP endpoint to me!

But if you look into the XSD namespace declaration of the namespace “http:” you will see the difference:

xmlns:http="http://www.mulesoft.org/schema/mule/nio-http"

It is for sure the http-nio-transport that is used and not the old-school http-transport!

Adding WebSocket semantics is done in the source code above by the declaration:

<http:websocket path="events"/>

That is what I call a powerful abstraction!!! Read the WebSocket specs and you will see what you get by this one-line declaration

From an architectural point of view I would prefer to use a BAM/CEP engine, such as Esper or Drools, with the responsibility to produce the messages to be pushed to the WebSocket clients. The BAM/CEP engine would typically use wire tapping of the messages mediated by Mule ESB to detect both events and non-events of interest as a base for the messages pushed to the WebSocket clients.

For the scope of this test a simpler solution is used with a timer based creation of the messages:

<flow name="websocket-event-generator">

<poll frequency="1000">

<custom-processor

class="com.mulesoft.demo.mule.websocket.CreateEvent"/>

</poll>

<http:websocket-writer path="events" />

</flow>

Streaming messages to WebSocket clients is done with the one-liner:

<http:websocket-writer path="events" />

Isn’t that, as well, a very nice level of abstraction?

Look out for a follow up blog on this blog where I’ll make the source code available for you to try it out on your own!