Blogg

Här finns tekniska artiklar, presentationer och nyheter om arkitektur och systemutveckling. Håll dig uppdaterad, följ oss på LinkedIn

Här finns tekniska artiklar, presentationer och nyheter om arkitektur och systemutveckling. Håll dig uppdaterad, följ oss på LinkedIn

In this blog we’ll do something quite different compared to the usual heavyweight stuff here on the blog. This blog post is 100 % guaranteed free from Microservices, Integration Patterns and ESB’s. We’ll build a “Golf Distance” smartwatch app for Garmin Connect IQ compatible devices.

First of all, what is a “Golf Distance” application and why do I want one on my watch? Basically, as a golfer, you always want to know the distance to the green (and bunkers, water etc.) from any given point on the hole you’re currently playing. Either you buy a laser rangefinder, use some smartphone app, buy an expensive purpose-built device or you hire a kick-ass caddie. Or you decide your brand new Garmin Fenix 3 multisport watch should be able to do the job too. Only that it doesn’t. Quite natural as Garmin has a separate product line for those club-swinging wanna-be Tigers/Jordans/Stensons. However - to my great enjoyment many new Garmin devices supports custom app development and deployment through their Garmin Connect IQ SDK. So instead of spending $300 or so for a another device, I decided to go down the DIY route and brew my very own distance measurement application.

Conceptually, it’s extremely simple. At 1-second intervals let the Positioning service give us the current geoposition of the device. Golf course data, e.g. hole information such as hole index, hcp, par and geoposition of the centre of the green, can either be loaded over the built-in HTTP client from an external service (requires BlueTooth connection to phone), stored in an app-specific http://developer.garmin.com/downloads/connect-iq/monkey-c/doc/Toybox/Application/AppBase.html#loadProperties-instance_method property or plain hardcoded. For the selected course and current hole, just perform a distance calculation between current watch geoposition and centre green geoposition and render this as text to the screen together with some hole info.

Example hard-coded course data, e.g. array of objects. Quite similar to javascript except the => instead of :

var testCourseHoles = [

{"hcp" => 7, "par" => 4, "lat" => 58.433293, "lon" => 11.376316},

{"hcp" => 13, "par" => 3, "lat" => 58.432704, "lon" => 11.374762},

...

...

]

This is the programming language you use when writing code for Connect IQ applications. It’s a nice little language having a lot more in common with Java, PHP or Python than C in my humble opinion. It’s object-oriented, uses reference count based memory management and is Duck Typed. I love this little quote from the official Monkey C docs about duck typing:

“Duck typing is the concept that if it walks like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it must be a duck”

The code is very readable and easy to follow if you’re used to some of the languages mentioned above. Here’s a little snippet from the GolfDistance application where we declare a onHold function that the underlying framework will execute when a given button has been pressed for more than N seconds:

class KeyDelegate extends Ui.InputDelegate {

function onHold(key) {

Sys.println("onHold");

Ui.pushView(

new Rez.Menus.MainMenu(),

new GolfDistanceMenuDelegate(),

Ui.SLIDE_UP

);

return true;

}

}

Here’s another snippet with “import”-statements from our main “view” class:

using Toybox.WatchUi as Ui;

using Toybox.Graphics as Gfx;

using Toybox.System as Sys;

using Toybox.Lang as Lang;

using Toybox.Position as Position;

using Toybox.Math as Math;

Very similar to imports in java, with each imported module given an alias. Yes, module. Those aliased imports aren’t classes, they’re modules now available to use in the namespace of the given .mc file we’re working in. Scoping is somewhat loose in Monkey C. A .mc file can contain any number of classes, functions and variable declarations. Variables and methods declared outside of the class scope becomes global and can be accessed throughout the application. Imported modules are made available to all classes and functions declared in the file.

Finally, let’s have a quick look at a function to calculate the equirectangular distance between two geopositions. It shows use of Math functions and built in number formatting on the duck-typed distance variable (probably a Double). No primitives in Monkey C btw.

function distance(lat1, lon1, lat2, lon2) {

var x = deg2rad((lon2 - lon1)) * Math.cos(deg2rad( (lat1 + lat2) / 2));

var y = deg2rad(lat2 - lat1);

var distance = Math.sqrt(x * x + y * y) * R;

return distance.format("%d");

}

Connect IQ applications runs in a virtual machine called Monkey Brains which exposes various APIs for accessing functionality from the underlying OS such a graphics, location services, storage and communication. The APIs are well documented and the limited scope for Connect IQ applications makes the APIs easy to comprehend and find one’s way around.

One of the quirkier things to consider is probably familiar to mobile developers - how does the underlying framework help me differ different devices from another? Some Garmin units have round screens, other rectangular. Some might have color displays, other b&w. Some units have certain sensors or features not available on others. Some uses touch screens, others buttons. Here is a list of current compatible devices directly from the manufacturer.

The Connect IQ SDK lets developers sort this out using a number of mechanisms. First of all, manifest XML files declaring app permissions, features required and similar stuff let’s the Garmin Connect Store show/hide your application from being installable on devices that’s never going to be able to run your app. Sounds rather similar to what Android does, right?

Furthermore, application resources such as layouts, images and fonts can be either defined in a device-specific manner or be overridden for certain types of devices. User input (be it from a touchscreen or a button) is handled through an Input Delegate that provides an abstraction letting you be key or touchscreen agnostic to a certain degree. Another mechanism is the ‘has’ keyword that during runtime can query the current device for support for a given API. This device doesn’t support barometric pressure? Ok, let’s hide that data field.

There’s a lot more to the Connect IQ SDK, but it’s time we got started with some actual coding.

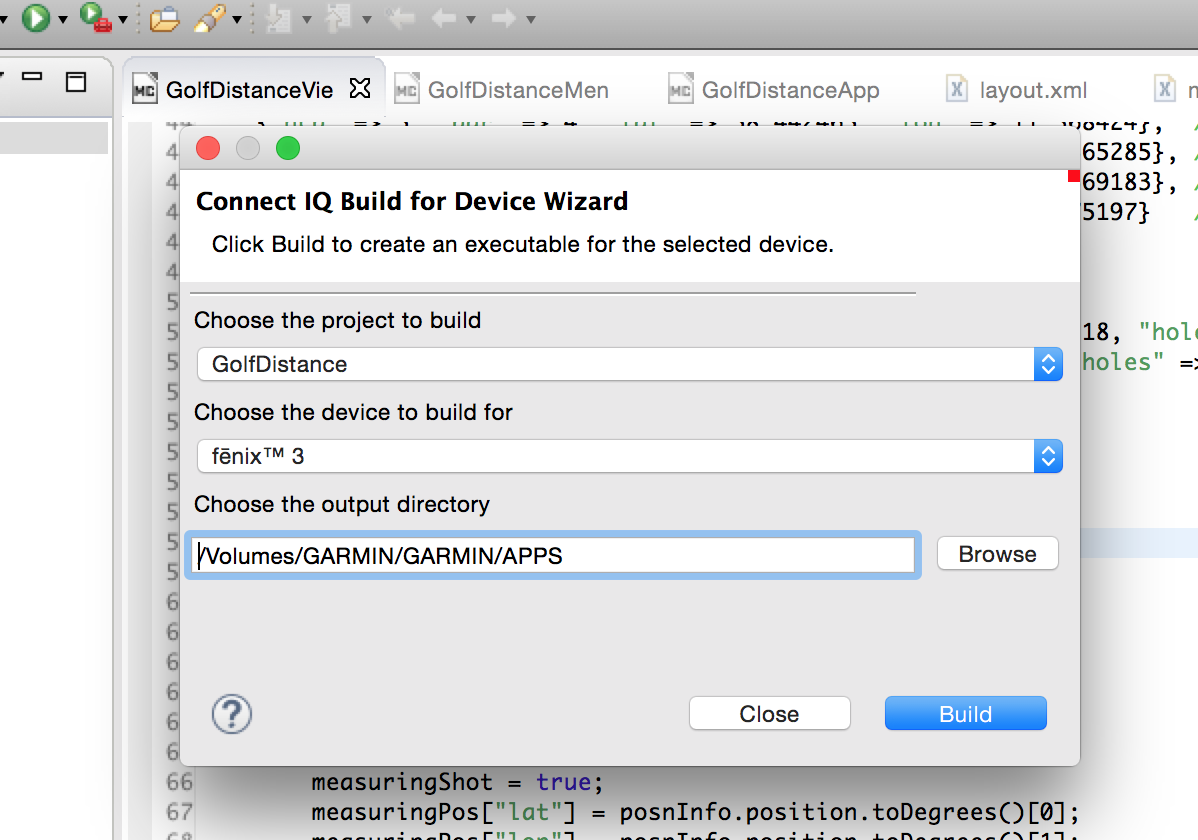

Stop right there. Coding? Where do I code this stuff? Emacs? Notepad? Vi? Is there an IDE? Yes, there is an IDE - or at least a nicely working Eclipse Plug-in for Eclipse Luna. After installing the plug-in and SDK, building applications and running them in the simulator or on your device is straightforward and trouble-free. Get started here.

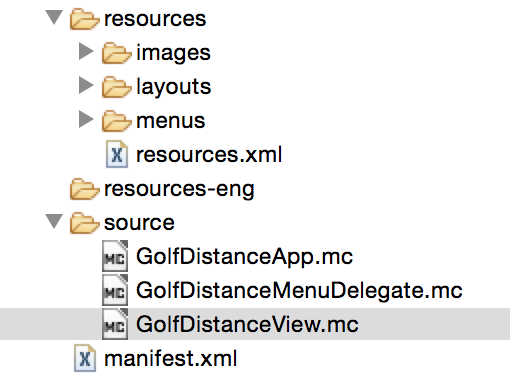

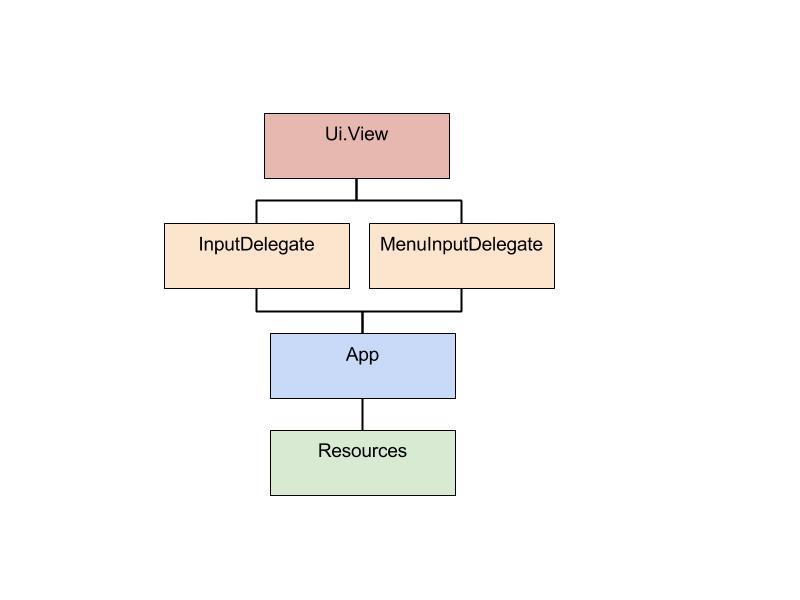

The heading sounds more heavyweight than it really is. The “architecture” of our application is more or less forced by Connect IQ and Monkey C conventions, but can be summarized in the sketch below:

“Resources” are the images, layouts, fonts, translatable texts and similar resources your application uses.

The “App” is the entry point, let’s say the “main()”-method lives there even though there is no main method. But so you Javaheads get it. The App class also has some lifecycle methods in it. Most importantly, it declares the initial view of the system and what InputDelegate subclass to use for handling user input.

class GolfDistanceApp extends App.AppBase {

//! onStart() is called on application start up

function onStart() { }

//! onStop() is called when your application is exiting

function onStop() { }

//! Return the initial view of your application here

function getInitialView() {

return [ new GolfDistanceView(), new KeyDelegate() ];

}

}

The two input delegates takes care of key presses (InputDelegate) and Menu options (MenuInputDelegate), an example of such code was displayed earlier in this blog post.

The Ui.View takes care of actual rendering and also a bit of application logic.

class GolfDistanceView extends Ui.View {

// Load your resources here

function onLayout(dc) {

setLayout(Rez.Layouts.MainLayout(dc));

}

// Called when this View is brought to the foreground. Restore

// the state of this View and prepare it to be shown. This includes

// loading resources into memory.

function onShow() {

Position.enableLocationEvents(Position.LOCATION_CONTINUOUS, method(:onPosition));

}

...... // We'll return to this!

It has a few lifecycle methods that let’s us specify the (XML-based) layout and an onShow() callback invoked when the View beomes visible.

That onShow() method invokes Position.enableLocationEvents that in our case tells the OS to give us continuous positional updates and to hand them as they become available to the onPosition method. Note the method reference using :[methodName]. Pretty nice!

function onPosition(geoPositionInfo) {

posnInfo = info;

Ui.requestUpdate();

}

Above, we see us assigning the geoPositionInfo to the globally declared variable posnInfo and then requesting a Ui re-render which kicks off the onUpdate() method.

The onUpdate() method contains the code that tells the UI rendering API what to render. To reduce memory and cpu cycles, the onUpdate() method needs to be explicitly invoked through Ui.requestUpdate() whenever the state has changed in such a way so the developer thinks the UI needs to be redrawn. In the GolfDistance application, each time a GPS position update is executed in the onPosition() method, we request an UI update. I also believe UI updates are performed when we let an Input event propagate from the event handler after our own stuff is done.

In the function onUpdate(dc) { method, we get a deviceContext as argument. Using the deviceContext, we can draw stuff to the screen. For a full set of what one can do, check the docs. In short, it’s quite standard canvas-drawing stuff such as drawText, drawBitmap, fillPolygon as well as useful helpers for getting screen dimensions and measuring text size given a certain font and string.

In the GolfDistance app, we just draw text in various sizes, though it would be cool to do some graphical representation of distance left to hole. The current drawing code looks like this:

dc.setColor( Gfx.COLOR_TRANSPARENT, Gfx.COLOR_BLACK );

dc.clear();

dc.setColor( Gfx.COLOR_WHITE, Gfx.COLOR_TRANSPARENT );

if( posnInfo != null ) {

var lat = posnInfo.position.toDegrees()[0];

var lon = posnInfo.position.toDegrees()[1];

var distanceStr = "" + distance(lat.toFloat(), lon.toFloat(),

courses[currentCourseIdx]["holes"][currentHoleIdx]["lat"],

courses[currentCourseIdx]["holes"][currentHoleIdx]["lon"]);

dc.drawText( (dc.getWidth() / 2), ((dc.getHeight() / 5) ), Gfx.FONT_NUMBER_THAI_HOT, distanceStr, Gfx.TEXT_JUSTIFY_CENTER );

} else {

dc.drawText( (dc.getWidth() / 2), (dc.getHeight() / 2), Gfx.FONT_SMALL, "Waiting for GPS position...", Gfx.TEXT_JUSTIFY_CENTER );

}

Simple enough - set current rendering color and clear screen using that color. Then switch to our preferred text rendering color and check whether we have any positionInfo available. If so, extract the latitude and longitude, pass those to the distance(..) method together with the coords from the current hole. Finally, call the drawText method where we specify x, y coords, font style (THAI_HOT?), the string to render and finally the justification. If there’s no positionData available yet (maybe the GPS hasn’t fixed the geoposition yet) we render an alternate text. That’s it!

The full rendering code also renders a bit more text, it looks like this while waiting for position in the Simulator:

This was another one of those “should this really be so simple” moments working with the Connect IQ SDK and its companion Eclipse plug-in.

Yes, the file system of the watch is mounted on the local computer and when the “.prg” file is placed in the APPS directory, the GolfDistance app will automatically appear in the list of applications. (See screenshot on top of this blog post)

Garmin has an “app store” for Connect IQ apps, watch faces etc. which developers can submit their apps to. It involves an approval process, so make sure developer guidelines are adhered to. I assume Garmin will not approve apps that doesn’t function on devices declared as compatible in the manifest or crashes if a given feature doesn’t exist and isn’t gracefully handled etc.

Garmin allows monetization on apps published through the app store, though it seems that involves having companion smartphone applications for money, ANT+ hardware or some kind of paid subscription service through Garmin Connect.

Well, there’s not actually that much more to this application. There’s a nice-to-have function that starts recording distance traveled on a keypress and shows it until one presses the same button again. Useful when you want to measure the actual length of a given shot or when you just want to practice your distance measuring skills. Also, by long-pressing the up button the app goes into its context menu where one can pick which of the (currently hard-coded) golf courses you’re currently playing.

Does it work? Absolutely! Used it quite a bit during the summer. Not that it helped my remedy my horrendous on-course performance, but that can’t be blamed on the watch.

The full source code can be found on my personal github page.