Blogg

Här finns tekniska artiklar, presentationer och nyheter om arkitektur och systemutveckling. Håll dig uppdaterad, följ oss på LinkedIn

Här finns tekniska artiklar, presentationer och nyheter om arkitektur och systemutveckling. Håll dig uppdaterad, följ oss på LinkedIn

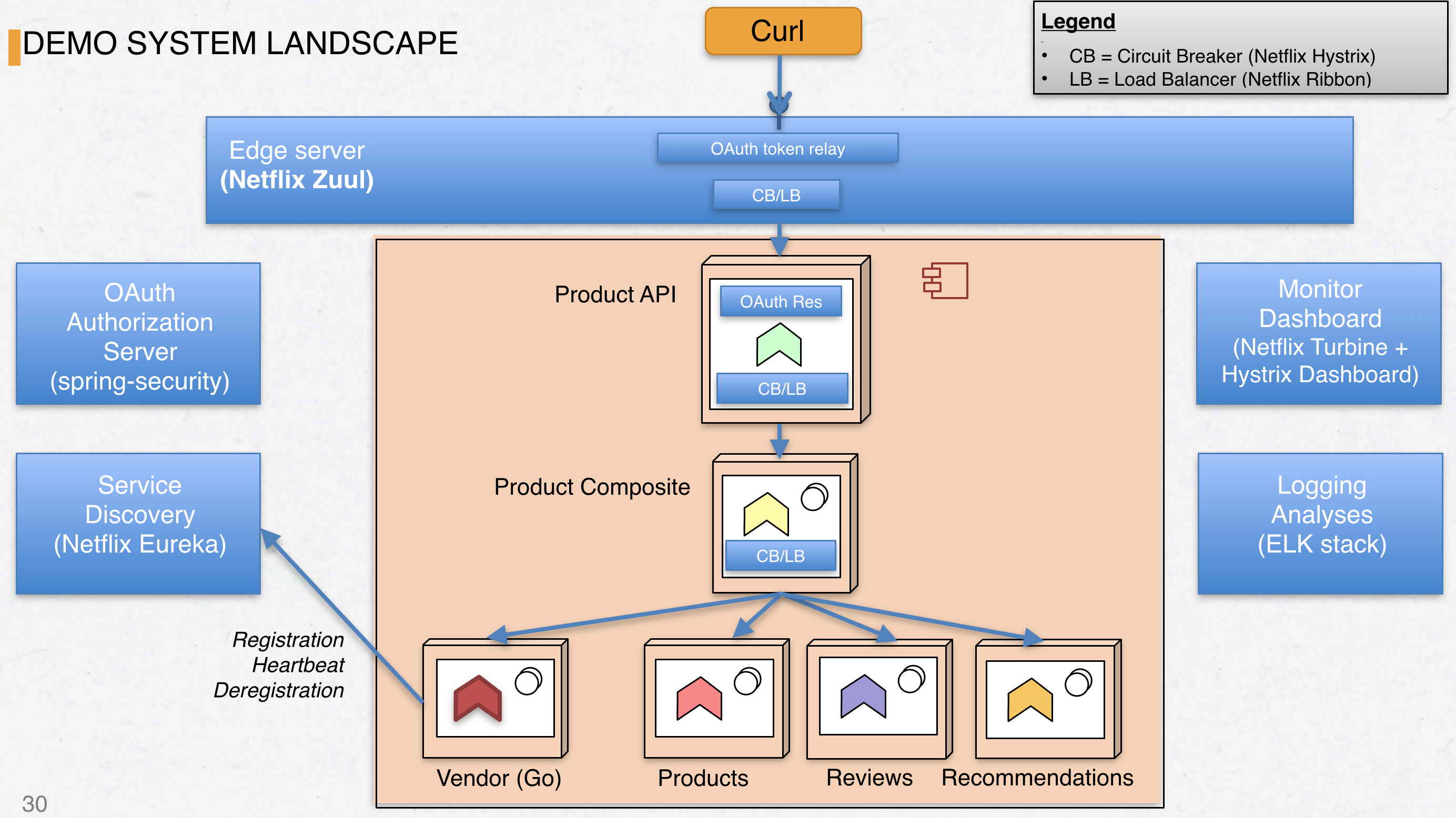

In this blog post, we’ll build a simple microservice using Golang and then add it to a Spring Cloud microservice landscape.

Building microservices using Golang may not be the first choice when you are targeting a Spring Cloud environment where most if not all participating applications are Java or JVM-based. However, Go have a number of things going for it - low memory footprint, fast startup/shutdown and being statically compiled for a specific OS / CPU architecture it puts very few requirements on the host OS - no Java Runtime Environment for example.

In this blog post, we won’t use any existing Go microservice frameworks such as go-kit. Instead we’ll just write a simple http server that will serve a list of “vendors” that neatly fits into the product/review/recommendation landscape environment established in the blog series from my colleague Magnus.

We can see the new ‘Vendor’ service in the bottom left corner with its interactions with the Eureka discovery service added for clarity.

The source code for the Go microservice can be found on github.

The updated final source code for the Spring Cloud landscape can be found here.

The creation of a Go-based microservice with Eureka registration and adding it to the Spring Cloud landscape can be divided into these five relatively distinct steps:

As previously stated, we’ll build most things from scratch this time. The main() method is of course a good starting point for looking at the Go code that starts our little service and registers with Eureka:

func main() {

handleSigterm() // Handle graceful shutdown on Ctrl+C or kill

go startWebServer() // Starts HTTP service (async)

eureka.Register() // Performs Eureka registration

go eureka.StartHeartbeat() // Performs Eureka heartbeating (async)

// Block...

wg := sync.WaitGroup{} // Use a WaitGroup to block main() exit

wg.Add(1)

wg.Wait()

}

The “vendor” microservice written in Go will return a JSON array of vendors for a given productId, e.g:

GET /vendor/{productId}

[{"id":0, "name":"Vendor no 1"},{"id":1,"name":"Some other vendor"}]

The HTTP server with routing is loosely based on this article from thenewstack.io, using the gorilla/mux library and the built-in http.ListenAndServe() function from the core http library.

func startWebServer(port string) {

router := service.NewRouter()

log.Println("Starting HTTP service at " + port)

err := http.ListenAndServe(":" + port, router)

if err != nil {

log.Println("An error occured starting HTTP listener at port " + port + ": " + err.Error())

}

}

The NewRouter() function returns a pointer to a mux.Router where the routes are fed into the router:

type Route struct {

Name string

Method string

Pattern string

HandlerFunc http.HandlerFunc

}

type Routes []Route // An array / slice of routes

var routes = Routes{

// Other routes omitted for clarity

Route{

"VendorShow",

"GET",

"/vendors/{productId}",

VendorShow, // Func reference.

},

}

Finally, the VendorShow method builds and returns a hard-coded list of vendors:

func VendorShow(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

vars := mux.Vars(r)

var productId int

var err error

if productId, err = strconv.Atoi(vars["productId"]); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

fmt.Println("Loading vendors for product " + strconv.Itoa(productId))

vendors := make([]model.Vendor, 0, 2)

v1 := model.Vendor{ Id: 1, Name : "Internetstore.biz",}

v2 := model.Vendor{ Id: 2, Name : "Junkyard.nu",}

vendors = append(vendors, v1, v2)

if len(vendors) > 0 {

w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "application/json; charset=UTF-8")

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK)

if err := json.NewEncoder(w).Encode(vendors); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

return

}

// If we didn't find it, 404

w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "application/json; charset=UTF-8")

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusNotFound)

if err := json.NewEncoder(w).Encode(model.JsonErr{Code: http.StatusNotFound, Text: "Not Found"}); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

}

Eureka is the discovery server from Netflix used in Spring Cloud. Non-java services can register with Eureka using the REST API of Eureka. Please note that Spring Cloud does not provide the /v2/ endpoints from the linked document. Registration, heartbeat and deregistration works fine as long as the /v2/ path segment is omitted.

A Eureka client library for golang called hudl/fargo actually exists. However, I’ve chosen to do some plain REST calls myself this time in order to understand the registration and heartbeat process better.

Given this code, a HTTP POST will be sent to the Eureka REST endpoint for registrations. Please note that the code above uses a hard-coded URI to Eureka. This should of course be externalized in some manner. For the registration POST body, one can choose between XML and JSON format, I’ve picked JSON:

var instanceId string

func Register() {

instanceId = util.GetUUID(); // Create a unique ID for this instance

dir, _ := os.Getwd()

data, _ := ioutil.ReadFile(dir + "/templates/regtpl.json") // Read registration JSON template file

tpl := string(data)

tpl = strings.Replace(tpl, "${ipAddress}", util.GetLocalIP(), -1) // Replace some placeholders

tpl = strings.Replace(tpl, "${port}", "8080", -1)

tpl = strings.Replace(tpl, "${instanceId}", instanceId, -1)

// Register.

registerAction := HttpAction { // Build a HttpAction struct

Url : "http://192.168.99.100:8761/eureka/apps/vendor", // Note hard-coded path to Eureka...

Method: "POST",

ContentType: "application/json",

Body: tpl,

}

var result bool

for {

result = DoHttpRequest(registerAction) // Execute the HTTP request. result == true if req went OK

if result {

break // Success, end registration loop

} else {

time.Sleep(time.Second * 5) // Registration failed (usually, Eureka isn't up yet),

} // retry in 5 seconds.

}

}

For details about how we send the HTTP POST, see DoHttpRequest source. I’ve reused that from another of my little Golang projects.

What’s more interesting is the JSON body we’ve posted:

{

"instance": {

"hostName":"${ipAddress}", // We're dynamically setting non-loopback IP adress here

"app":"vendor", // Name seen in Eureka

"ipAddr":"${ipAddress}",

"vipAddress":"vendor" // Important, used by Ribbon to look up endpoint adress

"status":"UP",

"port":"${port}",

"securePort" : "8443",

"homePageUrl" : "http://${ipAddress}:${port}/",

"statusPageUrl": "http://${ipAddress}:${port}/info",

"healthCheckUrl": "http://${ipAddress}:${port}/health",

"dataCenterInfo" : {

"name": "MyOwn"

},

"metadata": {

"instanceId" : "vendor:${instanceId}" // Metadata entry to differentiate instances when scaling.

}

}

}

The corresponding XSD (for the XML variant) can be found about halfway down here, it maps 1:1 to the JSON structure used above. The page urls are actually implemented by the routes.go and handlers.go files but are of course mainly placeholder implementations just there give some semi-proper response. For example, dataCenterInfo must have either ‘MyOwn’ or ‘Amazon’ as values. There is a complex ‘amazonMetadataType’ with many Amazon-specifics we ignore in this blog post since we’re gonna run this on-premise using docker-compose.

In a microservice landscape, a container running a given service may be started or shut down at any time. We want our discovery service to be as up-to-date as possible with available service instances. What good is a large number of instances of a given microservice if the consumers cannot find them? The opposite is just as important - how do we make sure that our go microservice deregisters itself with Eureka when a supervising container framework decides to decrease the number of running instances? How a particular container handles shutdowns may vary. For this particular example with a Go-based microservice running in a docker container managed by docker-compose, it is sufficient to capture whenever the OS sends an interrupt signal or when a SIGTERM signal is received, e.g. Ctrl+C.

This piece of code listens for such signals and passes them onto a channel supervised by an anonymous function running in a goroutine:

func handleSigterm() {

c := make(chan os.Signal, 1) // Create a channel accepting os.Signal

// Bind a given os.Signal to the channel we just created

signal.Notify(c, os.Interrupt) // Register os.Interrupt

signal.Notify(c, syscall.SIGTERM) // Register syscall.SIGTERM

go func() { // Start an anonymous func running in a goroutine

<-c // that will block until a message is recieved on

eureka.Deregister() // the channel. When that happens, perform Eureka

os.Exit(1) // deregistration and exit program.

}()

}

The code above makes sure Eureka gets a deregistration HTTP DELETE before the container is shut down.

To speed things up, I created a little bash shell script to help with the build process. It’s actually quite informative:

buildall.sh

#!/usr/bin/env bash

export GOARCH=amd64

export GOOS=linux

go build -o bin/goeureka src/github.com/eriklupander/goeureka/*.go

docker build -t vendor .

export GOARCH=amd64

export GOOS=darwin

The GOARCH and GOOS environment variables tells go build what CPU architecture and OS to build the binary for. Since our docker base image is a linux/amd64 one, we start by setting this before running go build. Next, we build the docker container giving it the name ‘vendor’ with the current directory as base path. Finally, we change GOOS och GOARCH back to my developer laptop settings (OS X 10.11).

Next stop is obviously the Dockerfile that specifies what base image to use, which files to add and what to execute when the container starts:

Dockerfile

FROM ofayau/ejre:8-jre

MAINTAINER Micro Service <micro.service@gmail.com>

EXPOSE 8080

ADD bin/goeureka goeureka

ADD templates/*.json templates/

ENTRYPOINT ["./goeureka"]

ofayau/ejre:8-jre is a bit of an overkill since the image bundles a 32-bit JRE we have absolutely no use for when running a Golang microservice, but it keeps things consistent with the blog series. Next, we tell the container to expose port 8080 (which happens to be the port our little http listener binds to) and add the goeureka binary and any JSON files in the templates/ directory to the image. Finally, we specify that the container shall execute ./goeureka on startup. Doesn’t get much simpler, right?

As previously stated, we’ll integrate the Go microservice into a Spring Cloud landscape.

Now, we’re done with the Go code and can move over to the Spring Cloud environment from the blog series. If coding along - check out, switch to the M6-GO branch and build everything:

git clone git@github.com:callistaenterprise/blog-microservices.git

cd blog-microservices

git checkout M6-GO

./buildAll.sh

(This part requires you to have a working docker environment set up in accordance to blog series part 4)

In the branch checked out above all the changes below have already been applied. However, let’s walk through a number of the changes performed beginning with the easiest part, adding the vendor service to the end of docker-compose.yml

vendor:

image: vendor

links:

- discovery

This little snippet tells docker-compose to use the vendor image for the same named logical name vendor. Finally, the links attribute tells docker-compose that this service is allowed to access the discovery service, e.g. Eureka.

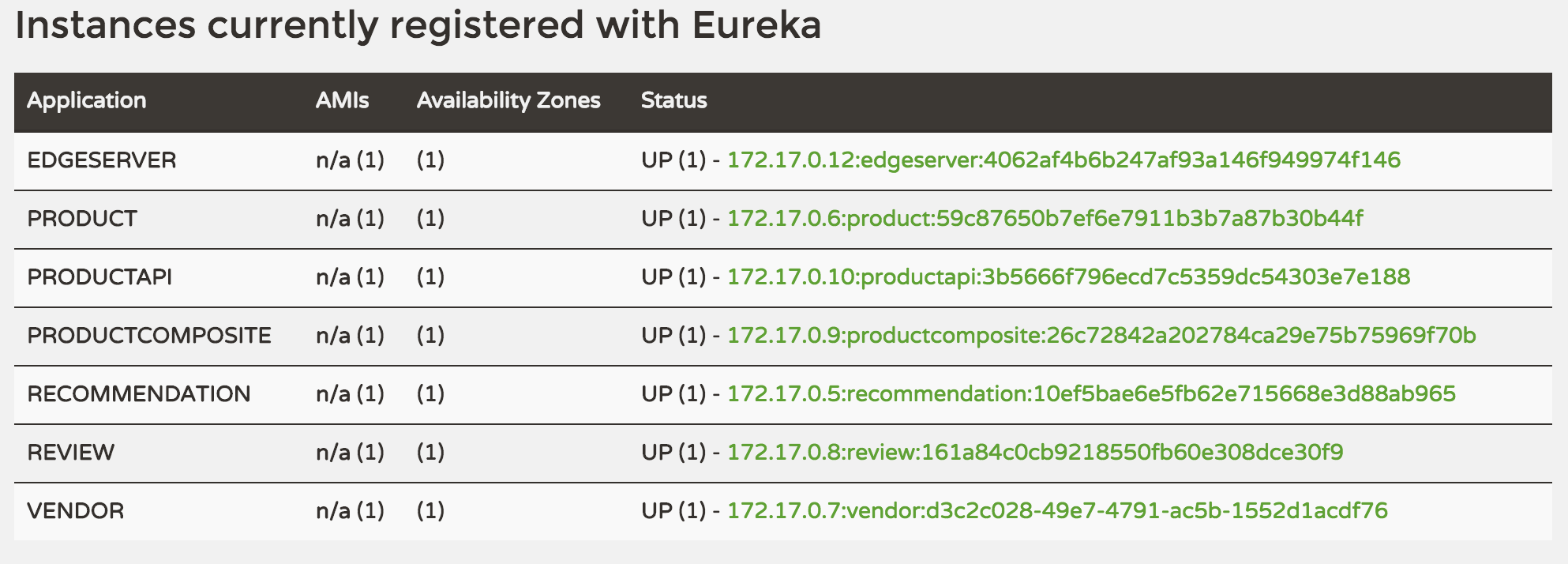

Try to start things up. The vendor microservice won’t be accessible from outside, but it might be a good idea to first make sure its registration with Eureka works properly:

docker-compose up -d

It will probably take a minute or two until everything has started. Since the discovery service is declared with “ports” in docker-compose.yml, it is accessible from outside of the internal docker landscape on port 8761. E.g:

discovery:

image: callista/discovery-server

ports:

- "8761:8761"

Unless you’ve entered a hostname record in your /etc/hosts file (or eq.) for the ‘docker’ host, you may need to look up the IP address of the docker network. One way to do this is by using docker-machine ls:

> docker-machine ls

NAME ACTIVE DRIVER STATE URL SWARM DOCKER ERRORS

default * virtualbox Running tcp://192.168.99.100:2376 v1.11.0

Open a web browser and enter your equivalent of http://192.168.99.100:8761 and you should end up at the Eureka start page.

It’s alive! Indeed, we see ‘VENDOR’ neatly in the list. Note that the 172.17.0.x links are unclickable - your browser has no access to the private network of the docker environment.

Now, shut it down again:

> docker-compose down

Time for some Java coding! Well - not much coding actually, mainly copy+paste and renaming stuff from blog series source. In ProductCompositeService.java, we’ve added some code to the getProduct method that will fetch vendors for us:

// 4. Get optional vendors

ResponseEntity<List<Vendor>> vendorsResult = integration.getVendors(productId);

List<Vendor> vendors = null;

if (!vendorsResult.getStatusCode().is2xxSuccessful()) {

// Something went wrong with getVendors, simply skip the vendors-information in the response

LOG.debug("Call to getVendors failed: {}", vendorsResult.getStatusCode());

} else {

vendors = vendorsResult.getBody();

}

return util.createOkResponse(new ProductAggregated(productResult.getBody(), recommendations, reviews, vendors));

Nothing fancy, the cool stuff happens inside integration.getVendors(productId):

@HystrixCommand(fallbackMethod = "defaultVendors")

public ResponseEntity<List<Vendor>> getVendors(int productId) {

LOG.info("GetVendors...");

URI uri = util.getServiceUrl("vendor"); // This is the cool part!!

String url = uri.toString() + "/vendors/" + productId;

LOG.debug("GetVendors from URL: {}", url);

ResponseEntity<String> resultStr = restTemplate.getForEntity(url, String.class);

LOG.debug("GetVendors http-status: {}", resultStr.getStatusCode());

LOG.debug("GetVendors body: {}", resultStr.getBody());

List<Vendor> vendors = response2Vendors(resultStr);

LOG.debug("GetVendors.cnt {}", vendors.size());

return util.createOkResponse(vendors);

}

Except some code that converts stuff etc. the nice thing here is that our new Vendor-fetching Java code works 100% the same way accessing our Golang-based service as fetching those Spring Boot-based review and recommendation services does. We look up the URL to the vendor service by asking Ribbon (the load balancer) for the address for ‘vendor’. This ‘vendor’ is the same string we entered in the registration JSON for ‘vipAddress’, i.e. Virtual IP Address. After that it’s just a matter of asking the RestTemplate to call the service for us att the returned URL, process the response and pass it up the call stack.

We also had to add a single line to ProductCompositeIntegration.java in order to enable load-balancing using Ribbon:

@Autowired

@Qualifier("loadBalancedRestTemplate") // ADDED THIS LINE!

private RestTemplate restTemplate;

Example console output after having fetched an OAuth token:

> export TOKEN=f7e6bec9-124d-4bf0-83d0-dfe27e5b3a20

> curl -H "Authorization: Bearer $TOKEN" -k 'https://192.168.99.100/api/product/1046'

{

"productId":1046,"name":"name","weight":123,

"recommendations":[{"recommendationId":1,"author":"Author 1","rate":1},{"recommendationId":2,"author":"Author 2","rate":2},{"recommendationId":3,"author":"Author 3","rate":3}],

"reviews":[{"reviewId":1,"author":"Author 1","subject":"Subject 1"},{"reviewId":2,"author":"Author 2","subject":"Subject 2"},{"reviewId":3,"author":"Author 3","subject":"Subject 3"}],

"vendors":[{"id":1,"name":"Internetstore.biz"},{"id":2,"name":"Junkyard.nu"}]

}

Awesome - we have the Go-based ‘vendors’ microservice fully functional!

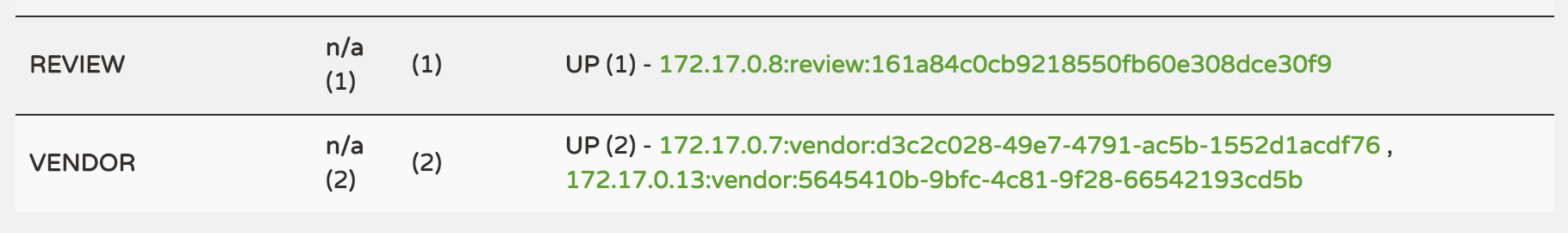

Of course, we can scale our vendor service just like any other service. Let’s add second instance of the vendor service.

> docker-compose scale vendor=2

Creating and starting blogmicroservices_vendor_3 ... done

Behind the scenes, docker-compose works its magic, spins up a new container with the ‘vendor’ image, launches the Go application which immediately registers itself with the Eureka server, making it visible to the Ribbon load-balancer.

Call the /api/product/{productApi} a few times, four in our case, and then check the log:

> docker-compose logs | grep vendors

vendor_1 | Loading vendors for product 1044

vendor_2 | Loading vendors for product 1042

vendor_1 | Loading vendors for product 1041

vendor_2 | Loading vendors for product 1046

Indeed, we see that the two ‘vendor’ instances are taking turns serving the product requests.

Running standalone on my OS X laptop, the ‘vendor’ microservice uses about 2 mb of RAM after starting up and running a dozen requests or so.

Moving on to docker, we can check memory use of our microservice landscape (edited for readability):

> docker stats

CONTAINER CPU % MEM USAGE / LIMIT

31d0c6ab9012 0.06% 126.2 MB / 2.1 GB <-- Monitor dashboard

e3c8c35def3b 0.27% 185 MB / 2.1 GB <-- Edge server

d5582272fe18 0.47% 220 MB / 2.1 GB <-- Product composite service

cb1d234fba5d 0.49% 218 MB / 2.1 GB <-- Product API service

9a9442abd475 0.33% 168.1 MB / 2.1 GB <-- Product service

21c0743bb845 0.27% 170.1 MB / 2.1 GB <-- Review service

6a300b04ce36 0.30% 163.1 MB / 2.1 GB <-- Recommendation service

6fd8d08cbf1c 0.00% 8.139 MB / 2.1 GB <-- Vendor service

602ff6640a7b 0.06% 146.5 MB / 2.1 GB <-- Auth server

3606d1ab8a55 0.72% 202.3 MB / 2.1 GB <-- Eureka

83e677dbc515 0.34% 97.89 MB / 2.1 GB <-- RabbbitMQ

Indeed, our running ‘vendor’ container uses ~8 MB of RAM while the similar review and recommendation services uses 160-170 MB each. If RAM is a limiting factor when scaling up a microservice environment, using Go may definitely be an option. However, the figures above is after just a dozen requests or so - memory use under load may be very different and the Spring Boot-based microservices may very well scale better without increasing their memory footprint significantly.

Both binaries I’ve built (darwin/amd64 and linux/amd64) produces an executable about 8 mb in size. Not very compact, but as previously stated these Go programs can be run on very “bare” containers.

Execution speed for returning the ‘vendor’ list from localhost is in the < 1ms range, though measuring latencies for a “dummy” service running on localhost is next to meaningless. I’ve done a bit of benchmarking of gorilla/mux in the past and it performs quite well, almost on par with Spring Boot. The case was a simple HTTP service fetching some data from a local MongoDB instance, both Spring Boot and Go could handle about 4K concurrent requests with 2-3 ms latency.

First and foremost, the vendor microservice itself has no security whatsoever, it fully depends on Docker mechanics (e.g. port exposal) and the Edge service for protecting its data. This particular instance, where the Go microservice is strictly internal and utilized by another (publicly exposed) microservice may be fine, but if we would expose it directly we would need to consider security in more detail. The Edge server handles a lot of those issues for us, but I would strongly recommend performing a security audit of any Go (micro)service exposed directly on the internet as net/http with Gorilla should be viewed more as a HTTP framework than a full-fledged production-hardened web server.

Furthermore, using a Go-based microservice as a replacement for the more complex “productcomposite service” would require implementing your own Discovery service lookups for other participating services, load-balancing those, circuit breakers and composing responses from aggregated data. Hopefully I can return to that topic later.