Blogg

Här finns tekniska artiklar, presentationer och nyheter om arkitektur och systemutveckling. Håll dig uppdaterad, följ oss på LinkedIn

Här finns tekniska artiklar, presentationer och nyheter om arkitektur och systemutveckling. Håll dig uppdaterad, följ oss på LinkedIn

Sometimes, you just need to leave all that microservice and enterprise stuff behind and do some old-fashioned coding just for fun. This blog post describes how I - just for the fun of it - wrote a Golang program that can control IKEA Trådfri home automation using CoAP over DTLS.

Important note: I am in no way whatsoever affiliated with IKEA or take any responsibility if this stuff breaks your IKEA stuff… ;)

The objective of this blog-post is to write a native Go application that can talk to the IKEA Trådfri gateway in order to query/control lights and other devices. There already exists quite a few 3rd party applications that performs exactly this feat such as coap-client, pytradfri and other more general-purpose CoAP-clients with DTLS support such as Eclipse Californium. I’ve drawn inspiration from several of these libraries, but wanted to see if I could do something similar using a pure Go implementation.

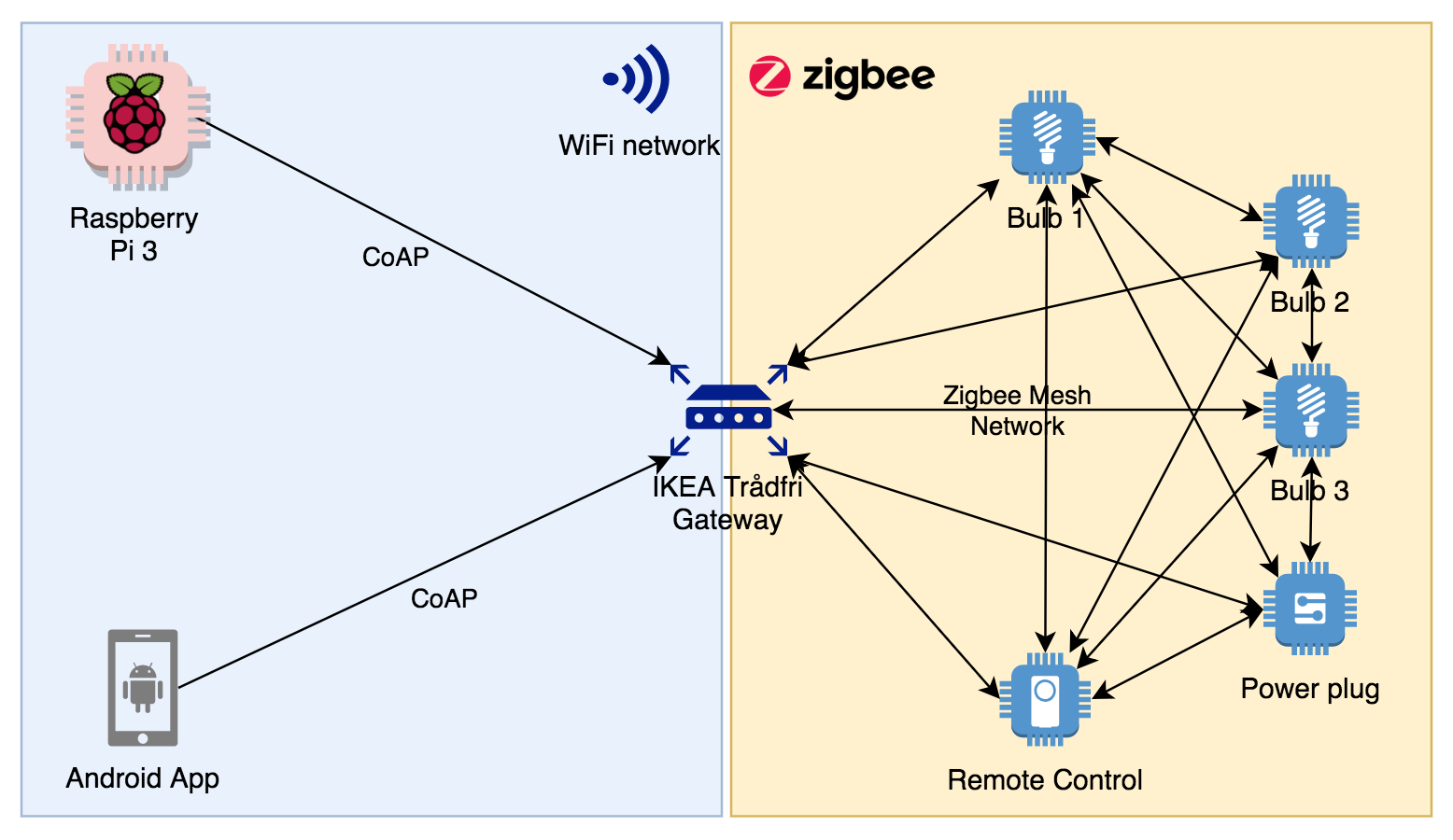

This blog post does not aim to be an advertising campaign for IKEA produts, but in order to put this venture into leisure-coding into some kind of context, I’ll describe the home-automation setup briefly:

The trådfri series provides a number of products for home automation including the following:

My personal setup currently consists of three light bulbs, one power plug, a remote and (most importantly for this blog post) their Gateway.

The Raspberry Pi 3 is the unit running the Go program this blog post is about. It works just as well on my dev Mac so it should be possible to run it on any OS/arch Golang supports.

Most (if not all?) mobile phones lacks the necessary radio (IEEE 802.15.4) to speak directly to bulbs etc over Zigbee. The gateway is thus a key component as it provides the interface from your WiFi network to the bulbs etc on the zigbee mesh network. Using a phone with Trådfri isn’t strictly necessary as the remote control can be used without WiFi, but I guess most users will use either the iOS or Android app to set things up.

Trådfri also supports integration with Apple HomeKit and Amazon Alexa, but that integration is not in scope for this blog post.

The objective of this blog post is to develop a standalone program using Go that can talk to the Gateway and both query the state of bulbs etc as well as controlling groups or individual devices. Communication from our Go program to the Gateway is based on the CoAP protocol running over DTLS 1.2, with CoAP payloads and identifiers based on LWM2M. I’ll get back to CoAP and DTLS a few sections down.

When starting this little venture, I set up the following objectives for the program:

The source code for the program can be found here:

https://github.com/eriklupander/tradfri-go

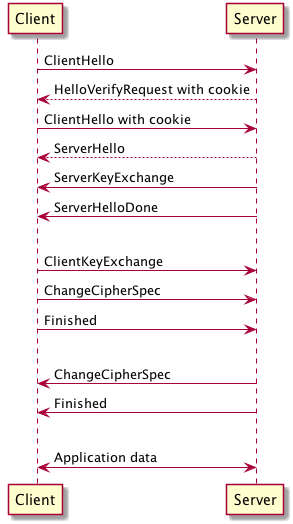

DTLS is short for “Datagram Transport Layer Security”, i.e. TLS over UDP. 1.0 and 1.2 of DTLS respectively maps closely to normal TLS 1.0 and 1.2, with a few differences to accomondate the differences between TCP and UDP transports.

I’ve based my tradfri-go application on the DTLS library from Jim W which has support for PSK authentication. However, due to an issue in the DTLS handshake code of Jim’s library when authenticating with the Trådfri Gateway, I’ve forked it with a little fix here for now.

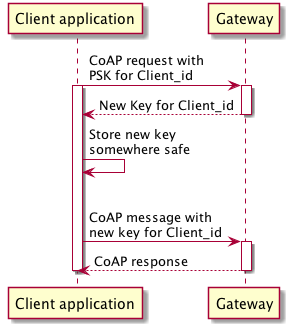

DTLS supports a number of authentication schemes including certificate-based solutions as well as “Pre-shared keys” (PSK), which is what the Trådfri series uses. The PSK of your Gateway is printed on the sticker on the underside of the gateway.

The PSK on the gateway is however only used for obtaining another key, an important piece of information I found here. The printed PSK is used to do an initial authentication with the gateway, which returns the key used for all subsequently interactions with the Gateway:

The handshake in DTLS (and TLS) has the purpose of exchanging keys, specifying cipher to be used etc between client and server in order to establish a securely encrypted connection. The details of this is typically handled by your DTLS library of choice, but I guess a simple overview of a DTLS handshake with PSK authentication can be fun to include for educational purposes:

For more details, I suggest reading RFC6347. The most significant difference between TLS and DTLS is that DTLS introduces a few measures to handle the inherently unreliable UDP transport, e.g. message loss, reordering, fragmentation and retransmissions. DTLS also introduces the Cookie exchange to prevent DoS attacks.

Anyway - the dtls library handles all of this for us as long as we can supply the correct Client_id, PSK and IP to the gateway.

Here’s the tradfri-go code where the handshake is performed behind the scenes. I’ve defined a struct DtlsClient that encapsulates the dtls.Peer and the message counter:

// DtlsClient provides an domain-agnostic CoAP-client with DTLS transport.

type DtlsClient struct {

peer *dtls.Peer

msgID uint16

gatewayAddress string

clientID string

psk string

}

// NewDtlsClient acts as factory function, returns a pointer to a connected (or will panic) DtlsClient.

func NewDtlsClient(gatewayAddress, clientID, psk string) *DtlsClient {

client := &DtlsClient{

gatewayAddress: gatewayAddress,

clientID: clientID,

psk: psk,

}

client.connect()

return client

}

Here’s the handshake/connect code:

func (dc *DtlsClient) connect() {

dc.setupKeystore()

listener, err := dtls.NewUdpListener(":0", time.Second*900)

if err != nil {

panic(err.Error())

}

peerParams := &dtls.PeerParams{

Addr: dc.gatewayAddress,

Identity: dc.clientID,

HandshakeTimeout: time.Second * 15}

fmt.Printf("Connecting to peer at %v\n", dc.gatewayAddress)

dc.peer, err = listener.AddPeerWithParams(peerParams)

if err != nil {

fmt.Printf("Unable to connect to Gateway at %v: %v\n", dc.gatewayAddress, err.Error())

os.Exit(1)

}

dc.peer.UseQueue(true)

fmt.Printf("DTLS connection established to %v\n", dc.gatewayAddress)

}

As one can see, the complexities of the DTLS handshake is fully handled behind the scenes. The returned dtls.Peer can then be used to write and read arbitrary []byte just like any socket, i.e:

// Write data over the socket

err = dc.peer.Write(data)

if err != nil {

return coap.Message{}, err

}

// Wait for response

respData, err := dc.peer.Read(time.Second * 3)

if err != nil {

return coap.Message{}, err

}

// do something with the response...

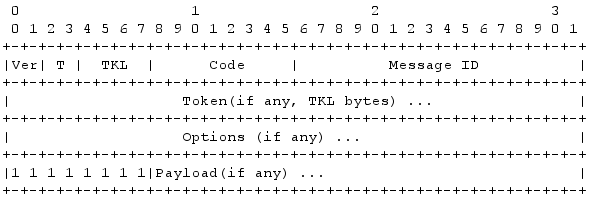

Defined in RFC7252, CoAP is a (quote from the RFC):

"specialized web transfer protocol for use with constrained

nodes and constrained (e.g., low-power, lossy) networks."

It re-uses much of the well-known RESTful paradigm with verb-based methods (GET, POST, PUT, DELETE) and servers providing resources under a URL.

Message payloads can be anything you want, e.g. JSON, XML or some arbitrary binary format, and the content-type of payloads can be specified with headers just like in HTTP. It also borrows response codes very similar to HTTP, such as “4.00 Bad Request” and “4.04 Not Found”. The 2.XX response codes indicating a successful request has slightly different semantics compared to HTTP. For example, no “2.00 OK” exists.

The actual messages are encoded into a compact format to conserve resources such as bandwidth and CPU-cycles. Again - the gritty details of which info that goes into which bit is out-of-scope for this blog post, but as reference the format looks like this:

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Writing a CoAP message serializer/deserializer may sound like fun, but perhaps not fun enough for me to do it given that there already exists a nice CoAP library for Go: go-coap by Dustin Sallings.

Dustin’s library makes creating/parsing CoAP-messages a breeze. Here’s an example where I build a GET message:

func (dc *DtlsClient) BuildGETMessage(path string) coap.Message {

dc.msgID++

req := coap.Message{

Type: coap.Confirmable,

Code: coap.GET,

MessageID: dc.msgID,

}

req.SetPathString(path)

return req

}

The coap.Message can then be serialized into a byte-array and written to the dtls.Peer and the response is as easily read and deserialized into a coap.Message.

I’ve wrapped the CoAP / Trådfri stuff into a struct TradfriClient that encapsulates the DtlsClient:

type TradfriClient struct {

dtlsclient *dtlscoap.DtlsClient

}

func NewTradfriClient(gatewayAddress, clientID, psk string) *TradfriClient {

client := &TradfriClient{}

client.dtlsclient = dtlscoap.NewDtlsClient(gatewayAddress, clientID, psk)

return client

}

Here’s the code that performs a GET for a given resource, for example the state of a bulb:

func (tc *TradfriClient) GetDevice(id string) (model.Device, error) {

device := &model.Device{}

resp, err := tc.Call(tc.dtlsclient.BuildGETMessage("/15001/" + id))

if err != nil {

return *device, err

}

err = json.Unmarshal(resp.Payload, &device)

if err != nil {

return *device, err

}

return *device, nil

}

The tc.Call proxies to the Call method of the DtlsClient which writes and reads plain bytes to/from the peer:

func (dc *DtlsClient) Call(req coap.Message) (coap.Message, error) {

// Serialize msg struct into raw CoAP payload

data, err := req.MarshalBinary()

if err != nil {

return coap.Message{}, err

}

// Write the payload into the peer (e.g. socket)

err = dc.peer.Write(data)

if err != nil {

return coap.Message{}, err

}

// Wait for the response

respData, err := dc.peer.Read(time.Second * 3)

if err != nil {

return coap.Message{}, err

}

// Deserialize the CoAP response into a coap.Message struct and return

msg, err := coap.ParseMessage(respData)

if err != nil {

return coap.Message{}, err

}

return msg, nil

}

Now that we can write and read CoAP messages over DTLS to the IKEA Gateway, it’s time to explore the capabilties of the CoAP API of the IKEA trådfri gateway.

The CoAP endpoints on the Trådfri Gateway are not an official API, though IKEA has stated an intent to someday make an API available for official use.

There are a number of unofficial resources describing the various CoAP endpoints and data structures that I’ve used to create this client:

The kind people in the links above have deducted a few basic guidelines that the Trådfri API seems to be built upon:

/15004 returns an array of identifiers for groups configured in your setup.

[131073]

/15004/131073 returns that group

{“9001”:”TRADFRI group”,”9002”:1550335495,”9003”:131073,”5850”:0,”5851”:0,”9039”:196608,”9108”:0,”9018”:{“15002”:{“9003”:[65536,65537,65538,65539,65540]}}}

/15001/65538 is the first light bulb in my setup, here’s a sample response:

{“9019”:1,”9001”:”Färgglad”,”9002”:1550336061,”9020”:1551635481,”9003”:65538,”9054”:0,”5750”:2,”3”:{“0”:”IKEA of Sweden”,”1”:”TRADFRI bulb E27 CWS opal 600lm”,”2”:””,”3”:”1.3.009”,”6”:1},”3311”:[{“5708”:42596,”5850”:1,”5851”:110,”5707”:5427,”5709”:30015,”5710”:26870,”5706”:”f1e0b5”,”9003”:0}]}

Let’s try to make some sense of the payload examples above. The CoAP messages largely follows OMA LWM2M, i.e. the “Open Mobile Alliance Lightweight Machine 2 Machine” standard. Their registry provides some descriptions on various codes. For example, we can see that 5850 is “an on/off actuator, which can be controlled, the setting of which is a Boolean value where True is On and False is Off.”.

However, a lot of those codes - especially those in the 9xxx range - doesn’t seem to be in a public registry, so some guessing, reading resources such as the links above and reverse-engineering the messages is required. Let’s break the device message down:

{

"9019": 1, // No idea

"9001": "Färgglad", // The name I gave this bulb in the Tradfri app

"9002": 1550336061, // Some unix timestamp

"9020": 1551635481, // Some unix timestamp

"9003": 65538, // Object id

"9054": 0, // No idea

"5750": 2, // Application Type

"3": { // Device type metadata?

"0": "IKEA of Sweden", // Vendor name

"1": "TRADFRI bulb E27 CWS opal 600lm", // Device type name

"2": "", // No idea

"3": "1.3.009", // Device type id?

"6": 1 // No idea

},

"3311": [ // Device values

{

"5708": 42596, // Something with color... ?

"5850": 1, // Device power on/off

"5851": 110, // Dimmer (0-255)

"5707": 5427, // Something with color... ?

"5709": 30015, // X color (CIE 1931)

"5710": 26870, // Y color (CIE 1931)

"5706": "f1e0b5", // Hex color

"9003": 0

}

]

}

If one were to build a user interface (a Web GUI for example) for viewing your IKEA Trådfri setup, I wouldn’t want the payload above exposed as-is for the client to use. I’d map the relevant stuff into a new JSON struct and pass that. In Go terms, a few structs like these could represent bulbs and power plugs:

type DeviceMetadata struct {

Id int `json:"id"`

Name string `json:"name"`

Vendor string `json:"vendor"`

Type string `json:"type"`

}

type PowerPlugResponse struct {

DeviceMetadata DeviceMetadata `json:"deviceMetadata"`

Powered bool `json:"powered"`

}

type BulbResponse struct {

DeviceMetadata DeviceMetadata `json:"deviceMetadata"`

Dimmer int `json:"dimmer"`

CIE_1931_X int `json:"xcolor"`

CIE_1931_Y int `json:"ycolor"`

RGB string `json:"rgbcolor"`

Powered bool `json:"powered"`

}

For other device types such as the Power plug or the remote, other fields may be relevant so I’m doing a bit of composition so common stuff can go into the DeviceMetadata struct.

Let’s get practical. The source code for this little program is on my github page.

Clone the source code and build using:

> go build -o tradfri-go

or produce binaries for different platforms:

> make release

mkdir -p dist

GO111MODULE=on go build -o dist/tradfri-go-darwin-amd64

GO111MODULE=on;GOOS=linux;go build -o dist/tradfri-go-linux-amd64

GO111MODULE=on;GOOS=windows;go build -o dist/tradfri-go-windows-amd64

GO111MODULE=on;GOOS=linux GOARCH=arm GOARM=5;go build -o dist/tradfri-go-linux-arm5

Start by finding out the IP-address to your Gateway. It’s probably possible to do a quick port-scan or multicast to find it, but I chose to simply go into the admin GUI of my NetGear router and find the gateway there.

The deviceId looks like this: GW-A1D4A0D1FF45

Then, I recommend setting an environment variable with this IP, for example:

export GATEWAY_IP=192.168.1.19

It’s also possible to pass the IP to the gateway to the “tradfri-go” executable using the –gateway_ip flag.

This is a 1-time step required before you can run in server mode or play around in the client mode. It will exchange the pre-shared key printed underside your Gateway for a new one bound to the client_id you specify. All subsequent calls to the Gateway from tradfri-go will then use these credentials for the DTLS handshake.

Running the command below will perform the token exchange and store your settings to a config.json file.

./tradfri-go --authenticate --client_id=MyCoolID --psk=TheKeyAtTheBottomOfYourGateway --gateway_ip=<ip to your gateway>

The new token is stored in the current directory in the file “config.json”, which contains your clientId, the new PSK and the Gateway IP you specified, e.g:

> cat config.json

{

"client_id": "MyCoolID",

"gateway_address": "192.168.1.19:5684",

"gateway_ip": "192.168.1.19",

"pre_shared_key": "the generated psk goes here",

"psk": "the generated psk goes here"

}

The program will try to read your gateway_ip, clientId and PSK from the config.json file for both client and server modes.

If you don’t feel like using config.json, you can either specify the configuration as command-line flags or using environment variables:

./tradfri-go --server --client_id MyCoolID122 --psk mynewkey --gateway_ip=192.168.1.19

or

> export CLIENT_ID=MyCoolID1122

> export PRE_SHARED_KEY=mynewkey

> export GATEWAY_IP=192.168.1.19

> ./tradfri-go --server

Configuration is resolved in the following order of precedence:

config.json -> command-line arguments -> environment variables

While my primary intent for tradfri-go is to run in its “server” mode, it also supports basic GET and PUT ops directly from the command-line that returns the raw JSON payload from the CoAP messages.

A few examples:

GET my bulb at /15001/65538:

./tradfri-go --get /15001/65538

{"9019":1,"9001":"Färgglad","9002":1550336061,"9020":1551721891,"9003":65538,"9054":0,"5750":2,"3":{"0":"IKEA of Sweden","1":"TRADFRI bulb E27 CWS opal 600lm","2":"","3":"1.3.009","6":1},"3311":[{"5708":65279,"5850":1,"5851":100,"5707":53953,"5709":20316,"5710":8520,"5706":"8f2686","9003":0}]}

PUT that turns off the bulb at /15001/65538:

./tradfri-go --put /15001/65538 --payload '{ "3311": [{ "5850": 0 }] }'

PUT that turns on the bulb at /15001/65538 and sets dimmer to 200:

./tradfri-go --put /15001/65538 --payload '{ "3311": [{ "5850": 1, "5851": 200 }] }'

PUT that sets color of the bulb at /15001/65538 to purple and the dimmer to 100:

./tradfri-go --put /15001/65538 --payload '{ "3311": [{ "5706": "8f2686", "5851": 100 }] }'

The colors possible to set on the bulbs varies. The colors are in the CIE 1931 color space whose x/y values in theory can be set using the 5709 and 5710 codes to values between 0 and 65535. You can’t set arbitrary values due to how the CIE 1931 (yes, it’s a standard from 1931!) works. Play around with the values, I havn’t broken my full-color “TRADFRI bulb E27 CWS opal 600lm” yet…

To start in the server mode, which provides the chi-based HTTP REST API, just add the –server flag:

./tradfri-go --server

Running in server mode on :8080

Connecting to peer at 192.168.1.19:5684

DTLS connection established to 192.168.1.19:5684

Now, you can use the simple RESTful API instead which returns more human-readable responses. Get a device:

> curl http://localhost:8080/api/device/65538 | jq .

{

"deviceMetadata": {

"id": 65538,

"name": "Färgglad",

"vendor": "IKEA of Sweden",

"type": "TRADFRI bulb E27 CWS opal 600lm"

},

"dimmer": 100,

"xcolor": 30015,

"ycolor": 26870,

"rgbcolor": "f1e0b5",

"powered": true

}

Get a group:

> curl http://localhost:8080/api/groups/131073 | jq .

{

"id": 131073,

"power": 0,

"created": "2019-02-16T17:44:55+01:00",

"deviceList": [

65536,

65537,

65538,

65539,

65540

]

}

We can PUT to the /api/device/{deviceId} endpoint to mutate the state of the bulb using three pre-defined settings:

> curl -X PUT --data '{"rgbcolor":"f1e0b5","power":1,"dimmer":254}' http://localhost:8080/api/device/65538

Just like the client mode, the application will try to use clientId/PSK from config.json or using env vars.

I havn’t built a “complete” API, just a few ones as a proof of concept. See router.go.

In its current state, the tradfri-go program isn’t that usable, it’s mainly been an exercise up until now trying to get my head around CoAP, DTLS and how to interact with the Gateway.

I’d say that it could be a good foundation for building something more advanced such as custom GUI or that idea of continuously collecting the powered/dimmming/colors state of your bulbs and eventually combining that data with time-of-day, weekday, weather data and whatnot with the intent of training a neural network that could automate your lights, blinders etc. given historical data and various environmental circumstances.

It should also be possible to use the github.com/eriklupander/tradfri-go/dtlscoap package as an external dependency to build something different around it.

Anyway - my primary intent was to have a good time writing some “non-enterprisy” code while learning something new, so I’m quite happy with this excerise! And not to forget - making lights blink is always fun!

Please help spread the word! Feel free to share this blog post using your favorite social media platform, there’s some icons below to get you started.

Until next time!

// Erik