Blogg

Här finns tekniska artiklar, presentationer och nyheter om arkitektur och systemutveckling. Håll dig uppdaterad, följ oss på LinkedIn

Här finns tekniska artiklar, presentationer och nyheter om arkitektur och systemutveckling. Håll dig uppdaterad, följ oss på LinkedIn

This blog post provides an overview of the different concepts behind reactive programming and its history.

Reactive programming has been around for some time but gained much higher interest during the last couple of years. The reason for this relates to the fact that traditional imperative programming has some limitations when it comes to coping with the demands of today, where applications need to have high availability and provide low response times also during high load.

To understand what reactive programming is and what benefits it brings, let’s first consider the traditional way of developing a web application with Spring - using Spring MVC and deploying it on a servlet container such as Tomcat. The servlet container has a dedicated thread pool to handle the http requests where each incoming request will have a thread assigned and that thread will handle the entire lifecycle of the request (“thread per request model”). This means that the application will only be able to handle a number of concurrent requests that equals the size of the thread pool. It is possible to configure the size of the thread pool, but since each thread reserves some memory (typically 1MB), the higher thread pool size we configure, the higher the memory consumption.

If the application is designed according to a microservice based architecture, we have better possibilities to scale based on load, but a high memory utilization still comes with a cost. So, the thread per request model could become quite costly for applications with a high number of concurrent requests.

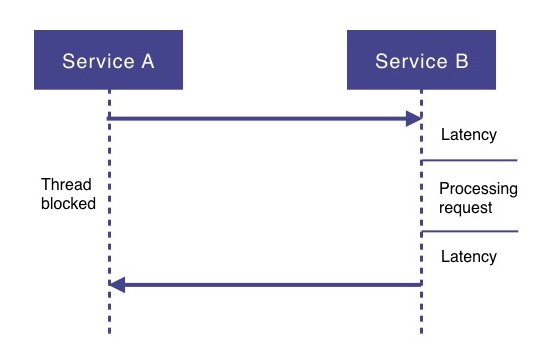

An important characteristic of microservice based architectures is that the application is distributed, running as a high number of separate processes, usually across multiple servers. Using traditional imperative programming with synchronous request/response calls for inter-service communication means that threads frequently get blocked waiting for a response from another service - which results in a huge waste of resources.

Same type of waste also occurs while waiting for other types of I/O operations to complete such as a database call or reading from a file. In all these situations the thread making the I/O request will be blocked and waiting idle until the I/O operation has completed, this is called blocking I/O. Such situations where the executing thread gets blocked, just waiting for a response, means a waste of threads and therefore a waste of memory.

Figure 1 - Thread blocked waiting for response

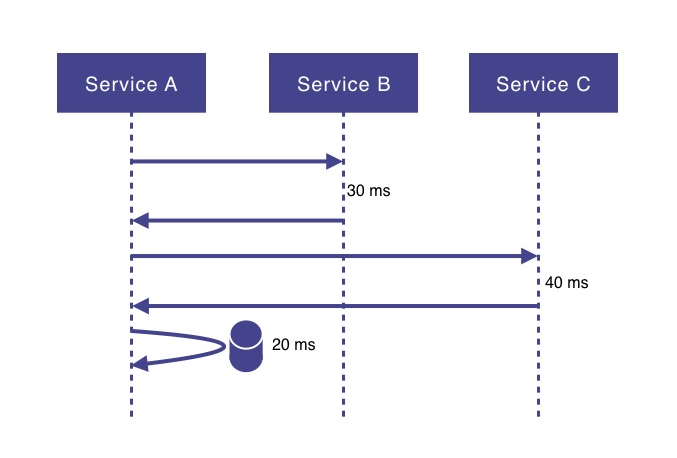

Another issue with traditional imperative programming is the resulting response times when a service needs to do more than one I/O request. For example, service A might need to call service B and C as well as do a database lookup and then return some aggregated data as a result. This would mean that service A’s response time would besides its own processing time be a sum of:

Figure 2 - Calls executed in sequence

If there is no actual logical reason to do these calls in sequence, it would certainly have a very positive effect on service A’s response time if these calls would be executed in parallel. Even though there is support fo doing asynchronous calls in Java using CompletableFutures and registering callbacks, using such an approach extensively in an application would make the code more complex and harder to read and maintain.

Another type of problem that might occur in a microservice landscape is when service A is requesting some information from service B, let’s say for example all the orders placed during last month. If the amount of orders turns out to be huge, it might become a problem for service A to retrieve all this information at once. Service A might be overwhelmed with the high amount of data and it might result in for example an out of memory-error.

The different issues described above are the issues that reactive programming is intended to solve. In short, the advantages that comes with reactive programming is that we:

A short definition of reactive programming used in the Spring documentation is the following:

“In plain terms reactive programming is about non-blocking applications that are asynchronous and event-driven and require a small number of threads to scale. A key aspect of that definition is the concept of backpressure which is a mechanism to ensure producers don’t overwhelm consumers.”

So how is all of this achieved?

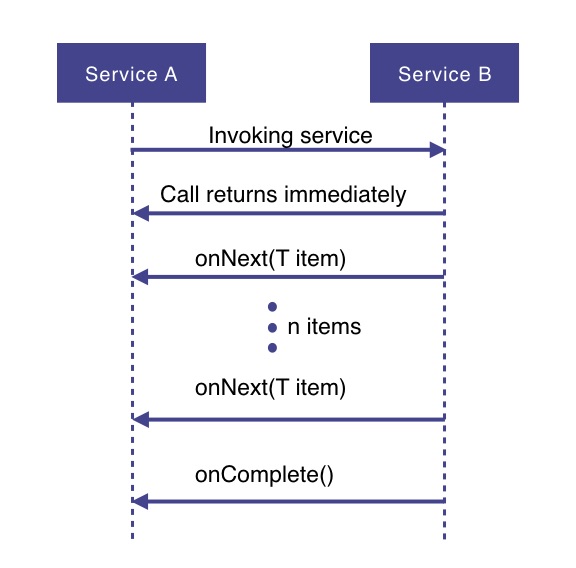

In short: by programming with asynchronous data streams. Let’s say service A wants to retrieve some data from service B. With the reactive programming style approach, service A will make a request to service B which returns immediately (being non-blocking and asynchronous). Then the data requested will be made available to service A as a data stream, where service B will publish an onNext-event for each data item one by one. When all the data has been published, this is signalled with an onComplete event. In case of an error, an onError event would be published and no more items would be emitted.

Figure 3 - Reactive event stream

Reactive programming uses a functional style approach (similar to the Streams API), which gives the possibility to perform different kinds of transformations on the streams. A stream can be used as an input to another one. Streams can be merged, mapped and filtered.

Reactive programming is an important implementation technique when developing “reactive systems”, which is a concept described in the “Reactive Manifesto”, highlighting the need for modern applications to be designed to be:

Building a reactive system means to deal with questions such as separation of concerns, data consistency, failure management, choice of messaging implementation etc. Reactive programming can be used as an implementation technique to ensure that the individual services use an asynchronous, non-blocking model, but to design the system as a whole to be a reactive system requires a design that takes care of all these other aspects as well.

In 2011, Microsoft released the Reactive Extensions (ReactiveX or Rx) library for .NET, to provide an easy way to create asynchronous, event-driven programs. In a few years time, Reactive Extensions was ported to several languages and platforms including Java, JavaScript, C++, Python and Swift. ReactiveX quickly became a cross-language standard. The development of the Java implementation - RxJava - was driven by Netflix and version 1.0 was released in 2014.

ReactiveX uses a mix of the Iterator pattern and the Observer pattern from Gang of Four. The difference is that a push model is used compared to Iterators normal pull-based behaviour. Along with observing changes, also completion and errors are signalled to the subscriber.

As time went on, a standardisation for Java was developed through the Reactive Streams effort. Reactive Streams is a small specification intended to be implemented by the reactive libraries built for the JVM. It specifies the types to implement to achieve interoperability between different implementations. The specification defines the interaction between asynchronous components with back pressure. Reactive Streams was adopted in Java 9, by the Flow API. The purpose of the Flow API is to act as an interoperation specification and not an end-user API like RxJava.

The specification covers the following interfaces:

Publisher:

This represents the data producer/data source and has one method which lets the subscriber register to the publisher.

public interface Publisher<T> {

public void subscribe(Subscriber<? super T> s);

}

Subscriber:

This represents the consumer and has the following methods:

public interface Subscriber<T> {

public void onSubscribe(Subscription s);

public void onNext(T t);

public void onError(Throwable t);

public void onComplete();

}

onSubscribe is to be called by the Publisher before the processing starts and is used to pass a Subscription object from the Publisher to the Subscriber

onNext is used to signal that a new item has been emitted

onError is used to signal that the Publisher has encountered a failure and no more items will be emitted

onComplete is used to signal that all items were emitted sucessfully

Subscription:

The subscriptions holds methods that enables the client to control the Publisher’s emission of items (i.e. providing backpressure support).

public interface Subscription {

public void request(long n);

public void cancel();

}

request allows the Subscriber to inform the Publisher on how many additional elements to be published

cancel allows a subscriber to cancel further emission of items by the Publisher

Processor:

If an entity shall transform incoming items and then pass it further to another Subscriber, an implementation of the Processor interface is needed. This acts both as a Subscriber and as a Publisher.

public interface Processor<T, R> extends Subscriber<T>, Publisher<R> {

}

Spring Framework supports reactive programming since version 5. That support is built on top of Project Reactor.

Project Reactor (or just Reactor) is a Reactive library for building non-blocking applications on the JVM and is based on the Reactive Streams Specification. It’s the foundation of the reactive stack in the Spring ecosystem. This will be the topic for the second blog post in this series!

A brief history of ReactiveX and RxJava

Build Reactive RESTFUL APIs using Spring Boot/WebFlux

Reactive Streams Specification