Blogg

Här finns tekniska artiklar, presentationer och nyheter om arkitektur och systemutveckling. Håll dig uppdaterad, följ oss på LinkedIn

Här finns tekniska artiklar, presentationer och nyheter om arkitektur och systemutveckling. Håll dig uppdaterad, följ oss på LinkedIn

In part 1 of this two part blog I introduced a pattern for integration testing a Spring Boot application that publishes events via Kafka.

In part 2 I will discuss what happens when the test suite grows, look in depth at the Kafka Consumer, and offer one solution for how to reduce long execution times.

The source code for the example application can be found by following the link.

Part 1 left us with a single working test that verified that a call to a RESTful endpoint resulted in 5 events being published to a Kafka topic. Running this test on my machine takes between 15 and 20 seconds.

Monitoring the JVM of the Gradle worker that executes the integration test with help from VisualVM shows minimal CPU usage and a single thread that spends most of its time sleeping. Using docker stats to monitor the container running the Spring Boot application shows a similar picture of inactivity. What’s going on?

The test uses a Kafka Consumer to consume events. The producer is working asynchronously and the test needs to poll for events for a reasonable amount of time to be certain that it has fetched all relevant events. In this example the Consumer will poll the Kafka broker for 10 seconds:

Consumer<String, String> consumer;

var records = consumer.poll(Duration.of(10, ChronoUnit.SECONDS));

Reasonable is a judgement call - choose too short a time period and the tests will fail or be flakey, choose too long a time and the test suite will run for what feels like an eternity. For this case 10 seconds of polling is judged to be reasonable. Note though that the test cannot execute for less than 10 seconds.

A single “happy path” test is unlikely to be sufficient for a comprehensive test. Adding error scenarios, new endpoints or complex behavioural tests will quickly grow the test suite. Even a relatively small application may have hundreds of tests and execution time will increase linearly.

To simulate this let’s run this test 100 times using the @RepeatedTest annotation on the test method. What happens? On my machine the entire suite always completes successfully but takes about 15 minutes to do so. This is probably reaching a pain point for developer - they will need to start the tests, get a cup of coffee, and hope things are done when they get back (and probably curse a little if the tests fail).

How can we make things run a little faster?

As the JUnit 5 user guide describes…

“By default, JUnit Jupiter tests are run sequentially in a single thread. Running tests in parallel — for example, to speed up execution — is available as an opt-in feature since version 5.3.”

This sounds like a way forward for faster testing! Let’s extend our Gradle task to enable parallel testing…

task<Test>("integrationTest") {

...

// Enable parallel testing in JUnit5 with a fixed thread pool

systemProperty("junit.jupiter.execution.parallel.enabled", "true")

systemProperty("junit.jupiter.execution.parallel.mode.default", "concurrent")

systemProperty("junit.jupiter.execution.parallel.config.strategy", "fixed")

systemProperty("junit.jupiter.execution.parallel.config.fixed.parallelism", "4")

}

This configuration will execute all test classes and all test methods in parallel. The fixed strategy has been chosen with a parallelism of 4 implying that up to 4 tests will be executed in parallel.

The next step is to enable our test class to be run in parallel:

@ExtendWith({CheckAvailabilityExtension.class})

@Execution(CONCURRENT)

public class DoSomethingEndpointTest {

}

Starting the test suite will cause 4 tests to start in parallel but each test fails. Why?

A quick check of the test output shows the problem:

KafkaConsumer is not safe for multi-threaded access

java.util.ConcurrentModificationException: KafkaConsumer is not safe for multi-threaded access

at org.apache.kafka.clients.consumer.KafkaConsumer.acquire(KafkaConsumer.java:2422)

at org.apache.kafka.clients.consumer.KafkaConsumer.acquireAndEnsureOpen(KafkaConsumer.java:2406)

at org.apache.kafka.clients.consumer.KafkaConsumer.poll(KafkaConsumer.java:1223)

at org.apache.kafka.clients.consumer.KafkaConsumer.poll(KafkaConsumer.java:1216)

...

Up until now all tests have been running sequentially and in the same thread. The test uses a Kafka Consumer to consume events. Configuring the Consumer is quite verbose and to avoid soiling the test code the Consumer is encapsulated in an EventsourceConsumer class. Setting up a Consumer is relatively expensive so the encapsulating class is implemented as a singleton to ensure that the Consumer is only instantiated once per test suite execution:

public class EventsourceConsumer {

private static EventsourceConsumer eventsourceConsumer;

public static EventsourceConsumer getInstance() {

if (eventsourceConsumer == null) {

eventsourceConsumer = new EventsourceConsumer();

}

return eventsourceConsumer;

}

private final Consumer<String, String> consumer;

private EventsourceConsumer() {

var props = new Properties();

...

props.put(ConsumerConfig.GROUP_ID_CONFIG, CONSUMER_GROUP_ID);

props.put(ConsumerConfig.AUTO_OFFSET_RESET_CONFIG, "earliest");

...

// Create the consumer using props.

consumer = new KafkaConsumer<>(props);

// Subscribe to the topic.

consumer.subscribe(Collections.singletonList(TOPIC));

}

/**

* Polls the topic until the max expiry time. Long blocking operation.

*/

public List<ConsumerRecord<String, String>> pollUntilExpires() {

...

var records = consumer.poll(MAX_POLLING_TIMEOUT);

consumer.commitAsync();

...

}

}

How can we then deal with the restriction that the Consumer can only be accessed by a single thread?

It is tempting to solve this by ensuring that each test instantiates its own Consumer. This will remove the concurrency problem but the tests will still fail. Why?

Above we have configured our Kafka Consumer to join a single consumer group. A consumer group is defined as such:

A consumer group is a set of consumers which cooperate to consume data from some topics. The partitions of all the topics are divided among the consumers in the group. As new group members arrive and old members leave, the partitions are re-assigned so that each member receives a proportional share of the partitions.

The intention here is to split up the workload but also to ensure no two Consumers are working on the same partition at the same time.

In our single threaded scenario there is a single Consumer consuming from all partitions. Adding more Consumers to the group will result in each Consumer working on a subset of the available partitions, or, if no unassigned partitions are available, no partition at all. As shown in part 1 our events are now distributed to a random partition on the topic. This means that a test with it’s own consumer may or may not be consuming from the partition where the event has been published - it is effectively up to chance whether our test will consume related events or not.

A consumer group maintains a register of the offset of the next record to consume allowing the group to maintain a position on the topic partitions - i.e. what has been consumed and what has not. When a read is committed (consumer.commitAsync) the broker moves on the offset so that the next Consumer to read from that partition will read the next record.

When a consumer group is created it needs to know where on the topic to start to consume and this can be configured with the auto.offset.reset parameter. In the example application the earliest value is chosen to instruct the group to start reading from the earliest offset (i.e. the beginning) of the topic. This was a deliberate choice to avoid timing issues and ensures the consumer group will consume events published prior to the group creation (which would have been skipped with the latest setting).

The example application deliberately creates a new consumer group with a unique name to avoid collisions between test suite executions which could result in events from previous executions being available to the current execution:

class ConsumerRecordStore implements Runnable {

private final static String CONSUMER_GROUP_ID = "eventsource_integrationtest_" + System.currentTimeMillis();

In theory it would be possible for each test to instantiate it’s own Consumer which is the sole member of a unique consumer group - this has not been investigated here. Using the earliest offset strategy above would require each test to filter all events ever published to the topic which may (or may not) place a significant overhead on the test.

Let’s try to seperate the delivery of events to the test from the consumption of events from the Kafka topic.

Let’s assume that a single Kafka Consumer is sufficient for a single test suite execution and that the Consumer is the sole member of a unique consumer group. That Consumer could happily consume from all partitions from the earliest offset and store all records in memory during the execution of the test suite. This is what the ConsumerRecordStore is intended to do:

class ConsumerRecordStore implements Runnable {

private final Consumer<String, String> consumer;

private Map<String, String> store;

private final ReadWriteLock lock = new ReentrantReadWriteLock();

ConsumerRecordStore() {

...

store = new HashMap<>();

consumer.subscribe(Collections.singletonList(TOPIC));

...

}

@Override

public void run() {

while (true) {

var records = consumer.poll(MAX_POLLING_TIMEOUT);

consumer.commitAsync();

lock.writeLock().lock();

records.forEach(r -> store.put(r.key(), r.value()));

lock.writeLock().unlock();

}

}

List<String> getRecords() {

lock.readLock().lock();

var records = store.values().stream()

.map(e -> e.value)

.collect(Collectors.toList());

lock.readLock().unlock();

return records;

}

Note that this class is package private and has been intentionally added to a different package to the test class. This class is not intended for direct use by any test.

The ConsumerRecordStore implements the Runnable interface. Thus the ConsumerRecordStore can be executed in its own thread and ensure the Consumer is not accessed by multiple threads.

As the Consumer has no direct relation to the test anymore it is free to poll the broker more frequently - polling has been set to 1 second (a blocking operation). Any events retrieved during the polling phase will be added to the store field.

The store field is a HashMap stored in memory. The store is private and cannot be accessed or manipulated by other classes. To ensure thread safety a ReadWriteLock is used; multiple reader threads can acquire a read lock except when a thread has acquired an exclusive write lock in which case they will be blocked until the write lock is released. Both read and write locks are acquired and released for the shortest period possible - i.e. when accessing or manipulating the store.

The next step is to make the stored events available to the tests.

The EventStore class is intended to expose filtered events to the tests and to hide the implementation details of the Kafka Consumer. This class is public and provides a single public method:

public class EventStore {

private final ConsumerRecordStore store;

public EventStore() {

this.store = new ConsumerRecordStore();

Executors.newSingleThreadExecutor().submit(store);

}

public List<String> getEvents(String traceId) {

try {

Thread.sleep(MAX_WAIT_TIME);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

// do nothing

}

return store.getRecords().stream()

.filter(s -> traceId.equals(JsonPath.parse(s).read("$['metadata']['traceId']", String.class)))

.collect(Collectors.toList());

}

}

In our previous single-threaded example the test waited 10 seconds for consumption of all events during the poll operation. In the EventStore this behaviour is replicated by forcing the thread to sleep for 10 seconds on a call to getEvents. Once the operation is resumed records can be fetched from the ConsumerRecordStore and filtered by trace id.

It is important to note that the ConsumerRecordStore will return all events that it has consumed since the start of the test suite.

The last step is to make the EventStore available to the test. This can easily be done using a JUnit5 ParameterResolver extension to pass the EventStore instance to the constructor.

public class EventStoreResolver implements ParameterResolver {

private static final EventStore EVENT_STORE = new EventStore();

@Override

public boolean supportsParameter(ParameterContext parameterContext, ExtensionContext extensionContext) throws ParameterResolutionException {

return true;

}

@Override

public Object resolveParameter(ParameterContext parameterContext, ExtensionContext extensionContext) throws ParameterResolutionException {

return EVENT_STORE;

}

}

Note that the intention here is to ensure instantiation of the EventSource once and only once. If the EventStore is instantiated multiple times then there will be multiple ConsumerRecordStore instances. This could be a problem if there is collision on consumer group id (a real possibility when the group name uses the system timestamp as in this example) or lead to multiple in-memory copies of events.

The EventStore instance can then be passed to the test in the constructor by activating the EventStoreResolver extension:

@ExtendWith({CheckAvailabilityExtension.class, EventStoreResolver.class})

@Execution(CONCURRENT)

public class DoSomethingEndpointTest {

private final EventStore eventStore;

public DoSomethingEndpointTest(EventStore eventStore) {

this.eventStore = eventStore;

}

...

}

…and the events are now available to the tests.

Now we are able to consume events in parallel tests yet the tests will still fail. Why? It turns out to be a timing issue…

As noted before the test suite can start before the Spring Boot application is fully initialised. The CheckAvailability extension is used to hold the tests in the BeforeAll lifecycle phase until the application is ready. In this case we are passing the EventStore in the constructor - before the BeforeAll lifecycle phase and possibly prior to the application being ready. As the application itself creates the topic the Consumer may be too eager and may not be assigned any partitions. No partitions mean no consumption and all tests fail.

To solve this we will use lazy initialisation in the EventStore:

public class EventStore {

private ConsumerRecordStore store;

public List<String> getEvents(String traceId) {

if (store == null) {

synchronized (this) {

if (store == null) {

store = new ConsumerRecordStore();

Executors.newSingleThreadExecutor().submit(store);

}

}

}

try {

Thread.sleep(MAX_WAIT_TIME);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

// do nothing

}

return store.getRecords().stream()

.filter(s -> traceId.equals(JsonPath.parse(s).read("$['metadata']['traceId']", String.class)))

.collect(Collectors.toList());

}

}

Note the use of synchronized to guarantee that eager threads do not unintentionally instantiate multiple ConsumerRecordStore instances.

Once this change is in place the tests suite starts to consistently return a successful result! By altering the number of threads in the thread pool we can start to see the promised performance improvements. The following numbers are a snapshot taken from my machine when running 100 tests:

Single threaded: 15 mins 28s

Fixed pool size 4 threads = 6m 7s

Fixed pool size 10 threads = 3m 1s

Fixed pool size 100 threads = 1m 5s

Fixed pool size 1000 threads = 1m 8s

From over 15 minute to close to 1 minute is a pretty good improvement and now the test suite is executing at a pace that a developer would find reasonable.

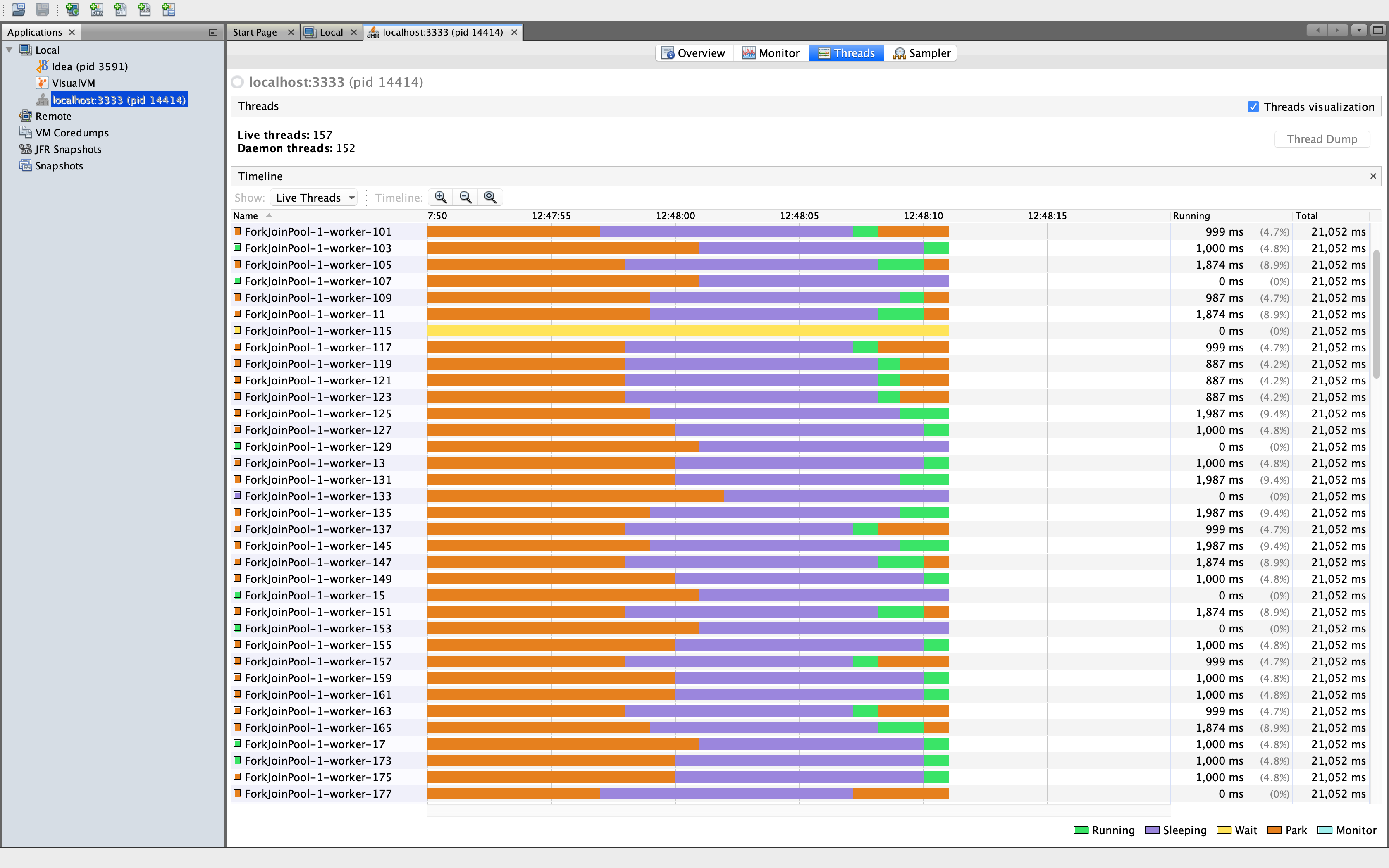

Below is a snapshot of activity with 100 threads case with help from VisualVM. It is possible to see the worker threads sleeping for 10 seconds followed by a short intensive burst of activity.

However there is one problem that lurks - the dreaded java.lang.OutOfMemoryError.

These example use an event that is not particularly large - as close to the default Kafka message limit of 1Mb as possible. Holding all events created by the test suite in memory is not a problem for a JVM with a max heap size of 512Mb.

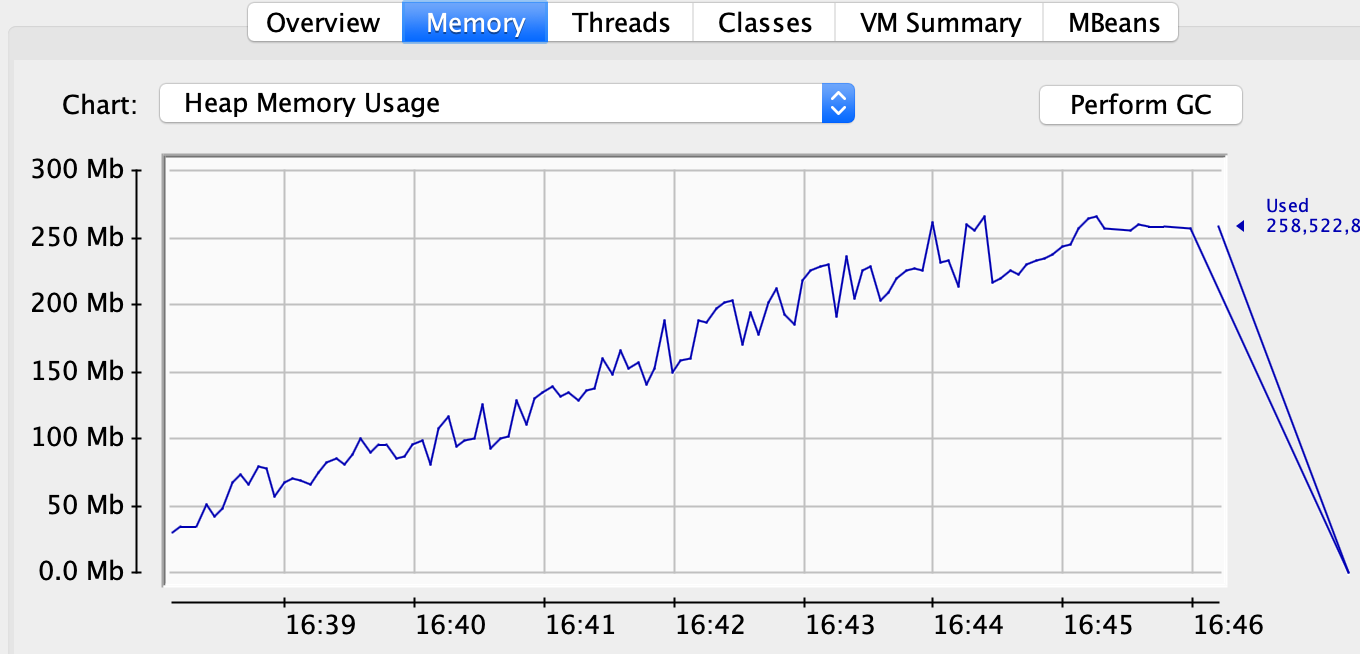

Our Kafka Consumer will be consuming events for the lifespan of the test suite and will start consuming from the beginning of the topic. To simulate this growing mass of in-memory events I restricted the JVM to max 256Mb in the Gradle task:

task<Test>("integrationTest") {

minHeapSize = "128m"

maxHeapSize = "256m"

The illustration below shows how the available memory slowly drops off during test execution until there is a final catastrophic failure in the form of a java.lang.OutOfMemoryError.

Storing all events in memory seems unreasonable when a test only need access to events for little over the 10 seconds that the test is executing. Why not dispose of events after a reasonable time period? To do this I extended the ConsumerRecordStore to perform a cleanup of messages more than 30 seconds old.

The first step is to define an ExpirableString class that contains both the value of the Kafka record and a time after which the record is no longer of interest. After every poll the ConsumerRecordStore will check to see if a cleanup is needed:

private void cleanUp() {

final long now = System.currentTimeMillis();

if (now <= nextCleanup) {

return;

}

lock.writeLock().lock();

nextCleanup = now + 30000l;

var newStore = store.entrySet().stream()

.filter(e -> e.getValue().expireTime > now)

.collect(Collectors.toMap(e -> e.getKey(), e -> e.getValue()));

store = newStore;

lock.writeLock().unlock();

}

Once again a write lock will be acquired to ensure that readers will not have access to the store during the clean up. After this no more memory problems occurred, even with 256Mb of available memory.

As I stated at the start of this blog it is essential that tests are reliable and reliability trumps speed. Long running tests will cause frustration, but unreliable tests can bring the most hardened developer to tears.

How can we check reliability in our new improved test suite? In this case I have spun up a Jenkins container and asked it to run the integration test task every 3 minutes. After several hours of continuous running things look stable!

In part 1 I introduced a pattern for integration testing a Spring Boot application that publishes events using Kafka. As demonstrated above testing using a single threaded model results in linear scaling of test suite execution time which can quickly become an irritant or worse. By seperating the consumption of events from the test itself using a JUnit5 extension it is possible to move to a parallel execution model which will provide a significant performance improvement without jeopardising reliability.

The source code for the example application can be found by following the link.

I hope this blog post has been of interest. Good luck with your testing!