Blogg

Här finns tekniska artiklar, presentationer och nyheter om arkitektur och systemutveckling. Håll dig uppdaterad, följ oss på LinkedIn

Här finns tekniska artiklar, presentationer och nyheter om arkitektur och systemutveckling. Håll dig uppdaterad, följ oss på LinkedIn

There is no denying the growing popularity of Kafka as a platform. It is probably safe to say that Kafka is now the de facto solution for asynchronous integration using a pub/sub pattern. Given the profusion of Kafka providers and solutions it has never been easier to get started.

If you are starting out on your journey to integrate applications with Kafka there are some important aspects that you will want to consider to in order to guarantee smooth operation at scale. In this two part blog I will look at some of these aspects and give some advice for potential Producers and Consumers.

This blog series will focus on the Apache Kafka Java client. Part one focuses on the Producer.

All of the scenarios below are simulated using a Kafka cluster based on the Confluent Kafka platform. The cluster consists of a single Zookeeper instance and three Kafka brokers. The cluster manages a single topic which is replicated across all three brokers to simulate the reliability guarantee that the cluster can offer. The topic has been configured with nine partitions which will likely be divided equally across the brokers in the cluster. All messages produced by the application will be of a consistent size 100kb and will not be compressed.

Messages are produced and consumed by a Micronaut microservice. Metrics from the Micronaut application are published to a Prometheus time series database using Micrometer and are visualised using Grafana. Docker Compose is used to start the application with access to a fully initialised Kafka cluster where one empty topic has been created.

The simulations performed should be considered as illustrative, not benchmarks - my laptop has limited memory, and network latency is negligible meaning almost instant replication between brokers.

When designing an application it is a good idea to have an idea of the throughput and reliability guarantees offered by your target cluster. Be aware that these may be significantly different between clusters, especially between test and production. A discussion of this is out of scope for this blog but a quick search for configure kafka cluster best practices will give you some ideas.

Code for the simulations can be found here.

The application will use the Micronaut Scheduler to publish a number of messages every second to the cluster.

The EventScheduler class will publish a defined number of messages using a thread pool of fixed size to simulate parallel activity in the application. The application will initially schedule one message per second and, after a three minute period of warm up, will increase the rate by one extra message every twenty seconds. After twenty minutes no further messages will be scheduled.

The EventPublisher class will use a Kafka Producer to publish the message to the topic. In this simulation we will use the blocking send() api to wait for a maximum of 15 seconds for a reply from the broker.

The application has been configured to enable Micronaut Metrics which are published to Prometheus and contain Kafka Producer metrics out of the box (for more information on these metrics see the section on producer metrics in this excellent post from DataDog). In addition some more metrics have been added to aid the simulation:

kafka.scheduler.event.count # Counter - number of events that have been scheduled

kafka.producer.send.timer # Timer - time taken in the Producer send() method

kafka.producer.confirmed # Counter - number of events with a response from send()

kafka.producer.unconfirmed # Counter - number of events with no response from send()

There is a good chance that your application will be sharing a Kafka cluster with other applications which are likely to have a wide array of use cases and needs. It is highly unlikely that all clients will always be producing and consuming at a steady rate and there is a risk that one “misbehaving” client could adversely affect the others. Fortunately the cluster can protect itself by using Quotas to try to slow the over eager client.

In this first simulation we will throttle the application using the (deprecated) producer quota configuration (quota.producer.default) on all brokers to restrict the client to 1Mb per second. Back pressure will be applied once the scheduler starts to pass a rate of 10 messages per second.

The number of configuration parameters available for the Producer may seem daunting but fortunately there is plenty of good documentation around. I can highly recommend O’Reilly’s Kafka: The Definitive Guide especially for understanding the many timing configurations.

For this simulation the following configuration has been used:

acks: "1" # await acknowledgment from partition leader only

buffer.memory: 10485760 # buffer memory size to 10 Mb

delivery.timeout.ms: 30000 # max 30 seconds for delivery

request.timeout.ms: 8000 # max 8 seconds for in flight time

max.block.ms: 5000 # max 5 seconds for buffer

in.flight.requests.per.connection: 1 # one inflight message (removes batching)

retries: 0 # Producer will not retry

Correct configuration or the Kafka Producer is essential for success. In this example the acknowlegement configuration (acks) is set to only acknowledge a write from the broker that is the leader for the partition, and there is a risk that a single broker fails prior to replication leading to a dropped message - a risk that is acceptable for a simulation but maybe not for a production application.

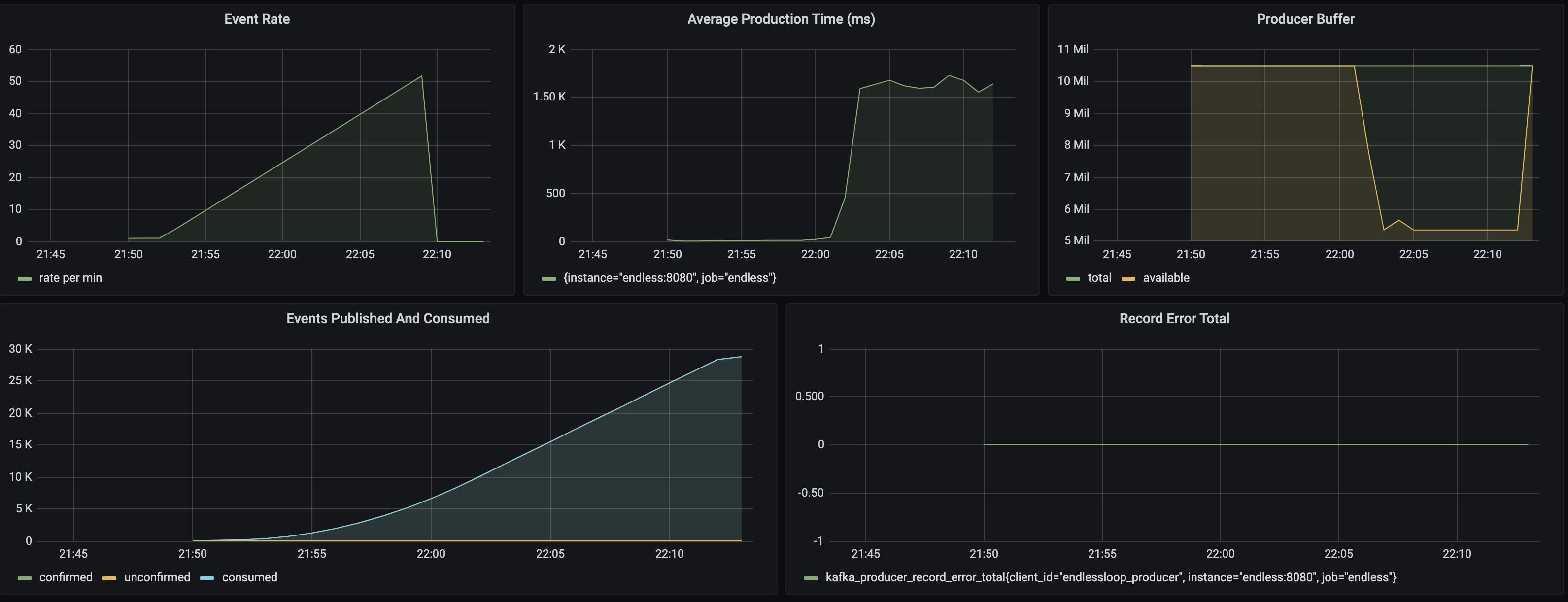

The following graph shows some interesting metrics from the simulation:

The application starts off running fine with response times in the millisecond level but after about 10 minutes the response times suddenly jump to about 1.5 seconds - a classic example of backpressure! This is good news for the broker cluster but can have implications for your application.

Consider an application that exposes a REST endpoint to the internet - every request does some work then publishes an event via Kafka to downstream systems. Traffic to the endpoint is difficult to predict - on a normal day there is a steady volume of traffic, but on a non-normal day, where traffic levels are high, backpressure from the broker may start to affect the responsiveness of the application. If the endpoint has an SLA in hundreds of milliseconds waiting seconds for a response from a broker is not an option (note: the default delivery timeout is 120 seconds - could you wait that long?).

Despite the load the application has remained reliable - the number of errors stays at zero and the number of consumed and published messages are the same. I have also added the Producer buffer metric which shows a dip to about 5Mb of free memory. The next scenario we will stress the buffer…

The Java Producer client contains an in-memory buffer for messages that are about to be sent to the Kafka broker cluster with a generous default size of 32Mb. This buffer presents a robust solution for separating the synchronous and asynchronous parts of an application whilst maintaining throughput. There are however a few aspects that you may need to consider especially where reliability is a factor.

In this example we are going to stress the system to provoke a transient failure. The configuration is as before but this time the buffer memory is reduced from 10Mb to 2Mb:

acks: "1" # await acknowledgment from partition leader only

buffer.memory: 2097152 # buffer memory size to 2 Mb

delivery.timeout.ms: 30000 # max 30 seconds for delivery

request.timeout.ms: 8000 # max 8 seconds for in flight time

max.block.ms: 5000 # max 5 seconds for buffer

in.flight.requests.per.connection: 1 # one inflight message (removes batching)

retries: 0 # Producer will not retry

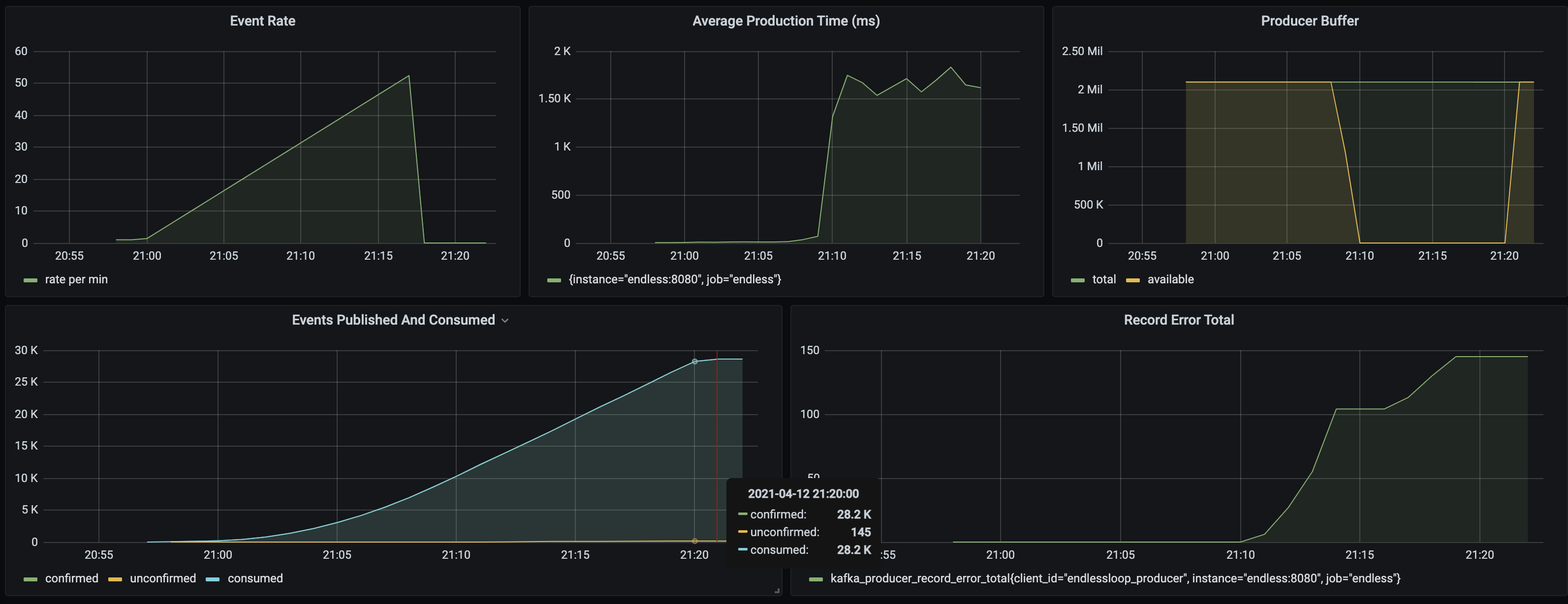

The broker enforces a quota of 1Mb per second so as the load increases the the in-memory buffer will start to fill up faster than it empties. Let’s have a look at the metrics:

As before we see can see that after a certain load response times rise and the size of the available buffer drops quickly to zero. In this simulation the error rate is no longer zero - the Producer has not been able to accept messages from the application and these have not been written to the topic. The application thinks it has produced 28765 messages during the simulation but if the offsets of the topic are summed only 28620 messages have been written - 145 messages are missing.

A quick look at the logs will show some exceptions:

java.util.concurrent.ExecutionException: org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.BufferExhaustedException: Failed to allocate memory within the configured max blocking time 5000 ms.

at org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.KafkaProducer$FutureFailure.<init>(KafkaProducer.java:1317)

at org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.KafkaProducer.doSend(KafkaProducer.java:986)

at org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.KafkaProducer.send(KafkaProducer.java:886)

In this simulation the success rate for publishing is 99.5% which may be considered good, especially for a system under stress, but is not 100%. The Kafka Producer is a remarkably reliable client and with careful configuration you can guarantee a very very high rate of success (although this is often a trade-off with throughput). As with all IT solutions attempting to guarantee 100% success all the time is unfeasible where cost increases exponentially for every “9” added.

Kafka offers a number of semantic guarantees for message delivery. In this case the application is using the Producer with an at most once guarantee - each message will be published once or not at all. But what are the consequences of a dropped message? For the producing application the consequences are often low. The consequences for your customers however may be higher and these consequences may take time to manifest or may turn up several steps further downstream.

It pays to engage your stakeholders when determining the correct guarantee for your application (and I strongly recommend reinforcing this choice time and time again so that it is well understood). If not, expect a panicked visit from your stakeholders and have a text editor, some credentials and access to kafkacat ready so that you can nervously try to find and manually republish dropped messages - a slow, and costly process where there is an ever present risk that you do more damage than good. The chances are you are running at scale and the panic from the first dropped message will lead you to find many more cases that your stakeholders will shortly ask you to fix.

Once your stakeholders have accepted that messages can be dropped you can consider strategies for measuring and handling this. These strategies often fall into two categories; reconciliation and republishing.

A reconciliation process would consider what the Producer thinks has been produced to what has been Consumed on the other side and will try to identify the delta. The ambition level of this process will vary depending on the use case - for example if Kafka is being used to transport logs a few missing messages may be tolerated whereas if the use case involves money a more rigorous process may be required (many banks still rely on skilled individuals to perform reconcilitation when moving large sums of money between accounts, often asynchronously using file transfers, for example).

The same is true for republishing; manually republishing each message using a tool such as kafkacat may be sufficient but may not scale and is risky. Other strategies can include publishing aggregated correctionaly posts (for example correcting balances). On the other extreme automated solutions may build feedback loops to identify dropped messages and to republish them automatically.

One word of caution - after a large incident it may be tempting to bundle up all unpublished messages and to run a script to republish them - make sure to throttle this script or you may overload the broker causing even more dropped messages and a second wave of republishing.

The cases above can be considered examples of transient failures where the system has a chance to recover if the load is reduced. A more difficult case is what happens if the failure is non-transient - when the system will not recover without intervention.

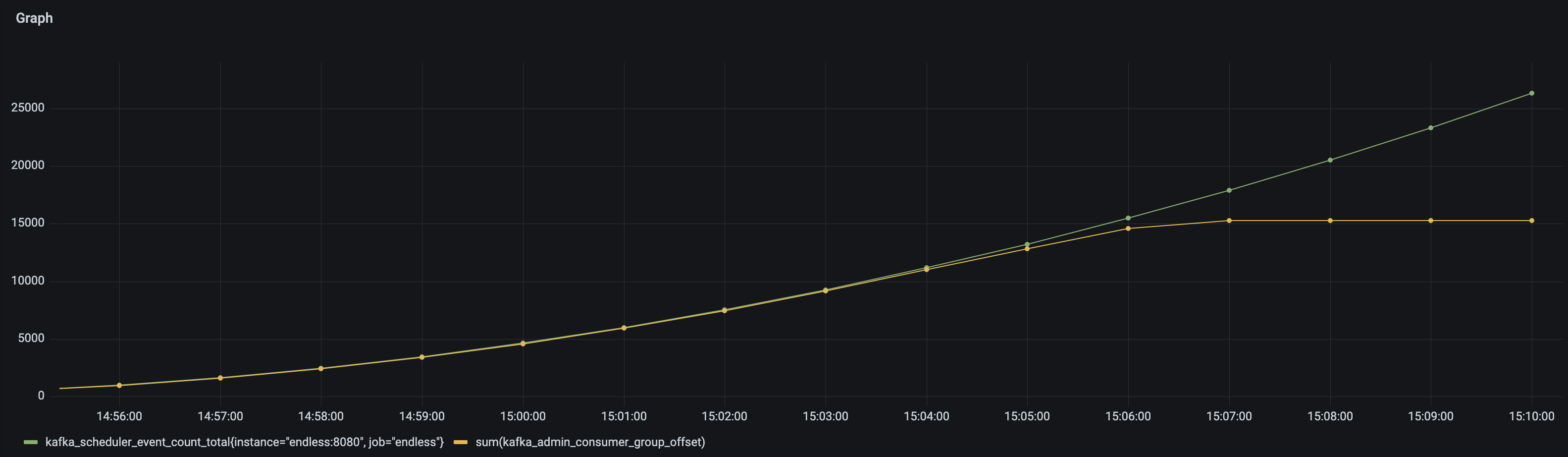

To simulate this we are going to rerun case 2 and take down the cluster whilst under stress. The following metrics show the number of messages the application thinks it has published (metric kafka.scheduler.event.count) and compare it to the sum of the offsets of all topic partitions - as we can see these diverge with the application thinking it is more successful than it is:

Another quick look at the logs will show more exceptions:

java.util.concurrent.TimeoutException: Timeout after waiting for 15000 ms.

at org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.internals.FutureRecordMetadata.get(FutureRecordMetadata.java:78)

at org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.internals.FutureRecordMetadata.get(FutureRecordMetadata.java:30)

at se.martin.endlessloop.producer.EventProducer.lambda$publish$0(EventProducer.java:65)

The application has waited 15 seconds for confirmation of publication from the Producer and then timed out. The application is unable to determine whether the message has been written to the topic and carries on regardless - the at least once guarantee holds. However, as in the case above, your stakeholders might not be so happy and you may be facing a major case of the republishing blues.

It may be that after some consideration an at most once guarantee is not enough and an at least once guarantee - where all messages are published but there may be duplicates - is more suitable. Kafka also provides an exactly once guarantee but a discussion of this area is considered out of scope for this blog post and may be the subject of a later post.

Can we achieve an at least once guarantee in the case of catastrophic failure? The Kafka Producer is a very robust client and can be configured to retry but all the retries in the world will not help if the broker cluster is down for a longer period of time. In order to ensure at least once for your application you will need to consider adding some form of data store - for example a distributed in-memory store such as Redis or even in a database (be careful though, these can also fail). This blog post by Andy Bryant on Processing guarantees in Kafka gives some useful ideas how this could be implemented.

On a side offloading to a data store is useful in bridging synchronous and asynchronous processes. Synchronous processes need to be responsive and with the Kafka Producer working in terms of seconds it makes sense to offload this work to a separate thread pool that can chew through the stored messages at its own pace leaving a more responsive synchronous process. In addition this allows the synchronous process to carry on working in the case of a non-transient failure.

If this is the strategy you choose then be aware of lag - the work that has been offloaded to a data store that is still to be done. It is a good idea to monitor this lag - ensure work is being done at an acceptable rate and set alarms when things get start to get full (especially if you are using a Redis cache). Note that even these scenarios are not totally watertight and a fallback solution may be to not publish the message at all. Hopefully this will be a very rare occasion but even here you can prepare for the horrors of manual republishing by dumping the message into a log or file (and monitor this with metrics to prove to yourself that it really is a rare situation).

This case has quickly evolved into a complex solution by adding a data store. Complexity increases further as you try to cover every failure scenario. It may be that the cost and complexity are simply not worth it and that synchronous calls should just fail if the broker is unavailable. It is however better if this is an active choice - design for failure in advance to save yourself dealing with complexity whilst in the middle of a stressful incident, mitigate the risk by having meaningful SLAs for your broker cluster in place.

This scenario has considered a catastrophic failure of the broker cluster, but a more likely scenario is a catastrophic failure of your application where, for example, the content of the Producer buffer may be lost. And what about graceful shutdown? Shutting the application in mid stream shows the application thinks it is still producing whilst the logs say otherwise:

Exception in thread "pool-3-thread-393" java.lang.IllegalStateException: Cannot perform operation after producer has been closed

at org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.KafkaProducer.throwIfProducerClosed(KafkaProducer.java:893)

at org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.KafkaProducer.doSend(KafkaProducer.java:902)

at org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.KafkaProducer.send(KafkaProducer.java:886)

at org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.KafkaProducer.send(KafkaProducer.java:774)

at se.martin.endlessloop.producer.EventProducer.lambda$publish$0(EventProducer.java:63)

Be aware that non-transient failures are not always so dramatic. In these simulations I have deliberately chosen a fixed message size. If message size varies and a message is greater than the max.message.bytes size (default 1Mb) then you will need to intervene if you want to fulfill an at least once guarantee.

To handle when things go wrong you may decide to implement your own resilience. In this scenario we are going to rerun case 2 but this time the application will be really impatient and will wait only 1 second for a result from the Producer:

private RecordMetadata send(ProducerRecord<UUID, byte[]> record) throws InterruptedException, ExecutionException, TimeoutException {

var future = producer.send(record);

var recordMetadata = future.get(1l, TimeUnit.SECONDS);

return recordMetadata;

}

Let’s try to deal with potential timeouts by adding a Retry in the application logic that instructs the Producer to try again. For this we are going to use the Resilience4j Retry module and configure a maximum of 5 retries with exponential backoff.

private final RetryConfig retryConfig = RetryConfig.custom()

.retryExceptions(TimeoutException.class)

.ignoreExceptions(ExecutionException.class, InterruptedException.class)

.maxAttempts(5)

.intervalFunction(

IntervalFunction.ofExponentialBackoff(Duration.ofSeconds(1l), 2.0)

).build();

Note though that the Producer configuration is unchanged and will wait for up to 30 seconds for confirmation from the cluster.

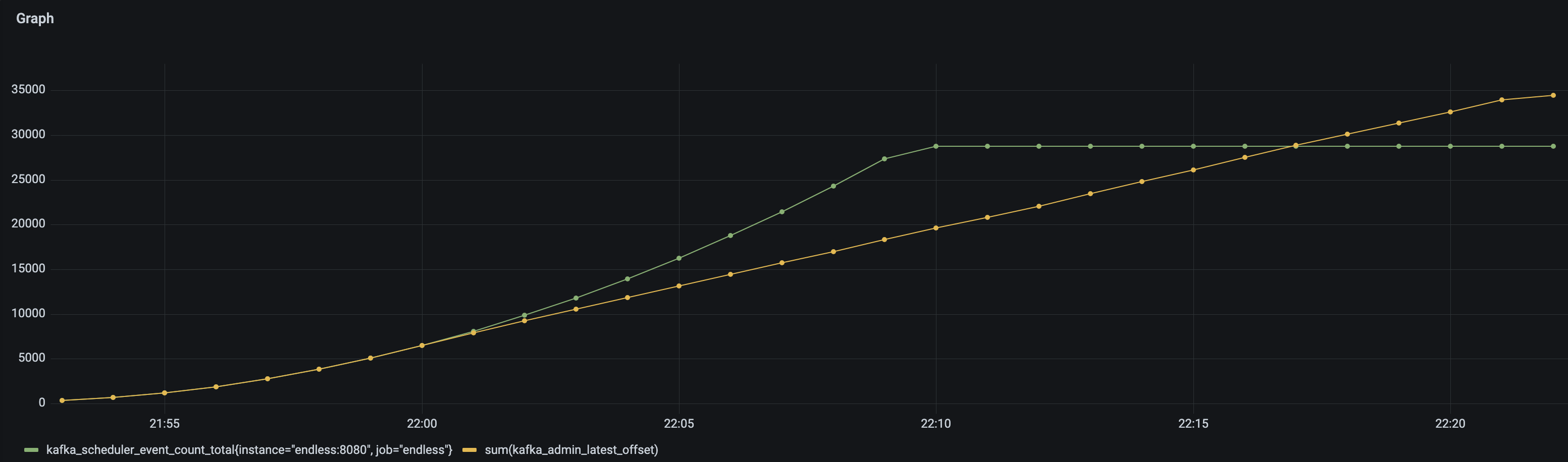

When this simulation is run the metrics show some interesting results. In the following diagram the green line represents the number of messages that the application thinks have been published and the yellow is the sum of the latest offsets in the topic (equivalent to the number that have really been published):

As the pressure builds we can see that the lines diverge - the number of published messages is lower than the application believes have been published. After 20 minutes the scheduler stops producing and gradually the number of published message starts to catch up (and at this point any outage in the application would cause message loss if these messages were not backed up in some form of data store). Finally the number of published messages starts to exceed the number of messages the application thinks it has published - 28765 messages expected to 34454 actually published - almost 20% more.

Adding our own homegrown resilience seems to extend the at least once guarantee of the Producer. This example is extreme but illustrates duplication becomes something that Consumers will have to handle. This could have negative effects if your application has promised an at most once guarantee.

I would argue that a better solution is to rely on the resilience strategies built into the Producer. By configuring retries with generous timeouts a TimeoutException should be a rare occurrence - effectively indicating a problem that requires intervention. In this case decoupling your synchronous processes from your Kafka Producer is almost essential - maximum wait times are likely to be counted in minutes.

In this blog post we have considered the Producer and discussed some scenarios that you may want to be aware of. The Producer is an industrial strength resilient client and in normal situations will run without problem. Under load cracks may show and there is always the chance of catastrophic failure. It pays to be prepared!

Note that decisions made here are likely to affect the behaviour of downstream Consumers. In certain scenarios it may be tempting to tailor the Producer to meet the needs of a specific Consumer - for example your client may demand guaranteed ordering of messages. If this is the case and the integration takes on a more point-to-point nature then maybe a Kafka pub/sub solution is not what you need and either a synchronous http based solution or an asynchronous MQ based solution is a better fit.

Part two will consider the Consumer.