Blogg

Här finns tekniska artiklar, presentationer och nyheter om arkitektur och systemutveckling. Håll dig uppdaterad, följ oss på LinkedIn

Här finns tekniska artiklar, presentationer och nyheter om arkitektur och systemutveckling. Håll dig uppdaterad, följ oss på LinkedIn

Recently, a proposal for adding low-level SIMD support to Go was “Accepted” and will be included in Go 1.26 as a GOEXPERIMENT. In the last part I took a look at “thinking in SIMD” in regard to structuring data for SIMD use. In this part, we’ll become more practical, looking at converting a scalar ray-intersection function for data parallelism.

I won’t go into any nitty-gritty details about the underlying math for performing ray/sphere intersections. Check out scratchapixel.com, it has many in-depth explanations around 3D graphics and ray tracing concepts.

The code for ray/sphere intersections is rather simple though, so given that the purpose of this blog post is to show we can SIMD-ify it using the Go SIMD experiment, converting it should be quite straightforward. Or will it?

Let’s start by looking at the non-SIMD Go code for a plain ray-sphere intersection, where ray consists of an origin and a direction expressed as 3D x,y,z coordinates in my own Vec4 type. Vec4 is just a typed [4]float32.

The sphere we want to intersect is represented by its center x,y,z coordinate and its squared radius.

func IntersectSphere(ray *Ray, center *Vec4, radiusSquared float32) (float32, bool) {

// Vector subtraction to get vector L that denotes a vector from sphere center to ray origin

var L Vec4

Sub(center, ray.Orig, &L)

// Compute dot product tCA of L and ray direction.

// If tca is negative, no intersection.

tca := L.DotProduct(ray.Dir)

if tca < 0 {

return 0.0, false

}

// Dot product of L with itself, then resolve d2 given lD minus tca squared.

lD := L.DotProduct(&L)

d2 := lD - tca*tca

// If larger than radius squared, no intersection.

// (i.e. ray passes outside the radius of the sphere)

if d2 > radiusSquared {

return 0.0, false

}

// Compute distances t0 and t1 (points where ray enters and exits sphere)

// from origin.

thc := float32(math.Sqrt(float64(radiusSquared - d2)))

t0 := tca - thc

t1 := tca + thc

// Find the lowest positive of t0, t1. If neither t0 nor t1 is positive,

// there were no intersection

// Swap if t0 is greater than t1

if t0 > t1 {

tmp := t0

t0 = t1

t1 = tmp

}

// If t0 is negative, use t1 instead.

if t0 < 0 {

t0 = t1

}

// If both t0 and t1 are negative, there was no intersection.

if t0 < 0 {

return 0.0, false

}

// t0 now holds the distance along the ray from

// ray origin to the intersection point.

return t0, true

}

This plain Go version performs a single intersection test. Next, we’ll prepare ray and sphere data to instead process 8 spheres per call.

This section is basically identical between the SIMD version of the code we’ll cover further on in this blog post, and for a for-loop based approach using plain Go.

The key characteristic we want is “vertically aligned” data. Let’s explain this using an example. In typical scalar code, we’d probably represent all spheres of a scene (let’s say 16 of them) as a []Sphere where Sphere would be a type encapsulating data for a single sphere:

type Sphere struct {

center *Vec4 // (x,y,z coords)

radiusSquared float32

}

In a “vertically aligned” set of data, we’ll instead define a Spheres type that contains x, y, z coordinates and the squared radius in discrete fields:

type Spheres struct {

CenterX []float32 // x coords for all spheres

CenterY []float32 // y coords for all spheres

CenterZ []float32 // z coords for all spheres

RadiusSquared []float32 // the squared radius for all spheres

Count int // Number of spheres in struct (e.g. same as len of the slices above)

}

In a plain go context, the pseudocode would look something like:

func IntersectSpheres(r *std.Ray, spheres *Spheres) (float32, int, bool) {

currentMinT := math.MaxFloat32

currentIndex := -1

for i := range spheres.Count {

// 1. Perform intersection test

// 2. If hit, check if closer than currentMinT. If closer, set currentMinT=t0 and currentIndex=i

// 3. Loop

}

// If currentIndex != -1, at least one sphere was intersected.

// if so, return currentMinT, currentIndex, true otherwise 0,-1, false

}

The neat thing is that the SIMD variant of the above pseudocode will follow the same structure, with the exception that the for-loop will increment by 8 for each iteration.

As outlined above, the basic premise is to use the vertically aligned Spheres struct, load x,y,z and radius data for 8 spheres at a time, and then use simd/archsimd code to perform the intersection testing using data parallelism.

Note: If the number of spheres isn’t a power of 8, we’ll have to pad with some fake spheres typically offset far behind the camera or similar. The benchmarking in section 5. runs with 16 spheres, which is an ideal scenario for this SIMD implementation.

We’ll break up the SIMD implementation in a number of smaller steps.

func IntersectSpheresSIMD(r *std.Ray, spheres *Spheres) (float32, int, bool) {

// Since we'll be processing 8 spheres at a time using 8 SIMD lanes,

// we need to use a SIMD broadcast with the ray origin and direction so

// we have SIMD registers with the ray's x,y,z values in all lanes.

rayOriginX := archsimd.BroadcastFloat32x8(r.Orig[0])

rayOriginY := archsimd.BroadcastFloat32x8(r.Orig[1])

rayOriginZ := archsimd.BroadcastFloat32x8(r.Orig[2])

rayDirectionX := archsimd.BroadcastFloat32x8(r.Dir[0])

rayDirectionY := archsimd.BroadcastFloat32x8(r.Dir[1])

rayDirectionZ := archsimd.BroadcastFloat32x8(r.Dir[2])

// Use a Float32x4 (to keep track of the currently lowest overall t (distance along ray)

currentMin := archsimd.BroadcastFloat32x4(math.MaxFloat32)

// Which sphere index that is the closest one.

currentIndex := -1

// Iterate in chunks of 8

for i := 0; i < spheres.Count; i += 8 {

// Load sphere x,y,z and radius data from the Spheres struct into SIMD registers

spheresCenterX := archsimd.LoadFloat32x8Slice(spheres.CenterX[i : i+8])

spheresCenterY := archsimd.LoadFloat32x8Slice(spheres.CenterY[i : i+8])

spheresCenterZ := archsimd.LoadFloat32x8Slice(spheres.CenterZ[i : i+8])

spheresRadiusSquared := archsimd.LoadFloat32x8Slice(spheres.RadiusSquared[i : i+8])

The above code should serve as a good example of loading vertically aligned data into archsimd.Float32x8 which is a typed representation of a 256-bit AVX2 register. We are now ready to start the intersection implementation.

// Compute vectors from sphere center to ray origin, component wise.

ocX := spheresCenterX.Sub(rayOriginX)

ocY := spheresCenterY.Sub(rayOriginY)

ocZ := spheresCenterZ.Sub(rayOriginZ)

// Compute dot product of center-origin vector we computed above and ray direction.

// The tcas variable now holds 8 dot products, one per sphere/ray intersection

tcas := ocX.Mul(rayDirectionX).Add(ocY.Mul(rayDirectionY)).Add(ocZ.Mul(rayDirectionZ))

This snippet shows how we compute the x,y and z dimensions for the sphere-center -> ray origin separately and then use them together with the likewise structured ray direction to compute 8 dot products at a time using simd/archsimd code.

Operator overloading isn’t a “Go thing”. Though I, for one, wouldn’t mind primitive vector types supporting operators. Writing

vecD := vecA + vecB * vecCis a lot more readable thanvecD := vecA.Add(vecB.Mul(VecC)). Oh, well. Can’t get everything you wish for.

The next snippet is extremely short:

// If all tcas are less than zero, there cannot be any hits this iteration,

// continue to next batch

if tcas.GreaterEqual(zeroes).ToInt32x8().IsZero() {

continue

}

Well - technically the if-statement above IS a branch, but as we’ll see any if-statements in the for-loop are purely for “exit early” purposes.

So, what’s going on here? If we look back at the plain Go version:

if tca < 0 {

return 0.0, false

}

it was an exit-early since a negative tca tells us that the ray cannot intersect the sphere currently being intersection tested, so we might as well exit early.

In the SIMD code, tcas.GreaterEqual(zeroes).ToInt32x8().IsZero() is our first acquaintance with a Mask. Masks are used a lot in SIMD code instead of if-statements. In this particular case, tcas.GreaterEqual(zeroes) will produce a archsimd.Mask32x8 containing non-zero values (-1) in all elements where the predicate was true. (zeroes is a archsimd.Float32x8 defined elsewhere containing 0.0 in all elements).

There are two important things to remember here:

archsimd API requires us to first convert the mask to a Int32x8 in order to access IsZero() that returns true if no elements in the mask were set. This feels a bit backwards. It would be more natural to use something like if tcsa.Less(zeroes), then exit early, but since IsZero() is the only way I’ve found to “cross into the non-SIMD barrier” of scalar code using simd/archsimd, I guess it’ll have to do for now.This section does not introduce something “new” SIMD-wise:

// Compute the squared magnitude of the element-wise sphere-center -> origin vectors.

// (This is essentially dot product on itself) lD then holds the squared magnitude per lane.

lD := ocX.Mul(ocX).Add(ocY.Mul(ocY)).Add(ocZ.Mul(ocZ))

// Then, also square tcas, tcaSquared holds the 8 dot products squared

tcaSquared := tcas.Mul(tcas)

// Element-wise subtracting of lD and tcaSquared produces

d2 := lD.Sub(tcaSquared)

// Next mask, d2 must be less than sphere radius squared to be a hit. If no d2 fulfills that criteria, exit early.

// I.e. read this if statement as: "if no d2's are less than its corresponding sphere's radius squared, then exit early."

if d2.Less(spheresRadiusSquared).ToInt32x8().IsZero() {

continue

}

// Compute distance to hit point(s).

thc := spheresRadiusSquared.Sub(d2)

thcSqrt := thc.Sqrt()

t0 := tcas.Sub(thcSqrt)

t1 := tcas.Add(thcSqrt)

Again, the if-statement with a mask test reads a bit backwards. Otherwise, this section shouldn’t cause too much trouble. At the end, t0 and t1 will contain eight distances each (one per lane), where at least one might be a real intersection.

Now we’re at the point where we have t0 and t1, each having 8 lanes (elements) with possible intersection distances. In the plain Go implementation:

// Find the lowest positive of t0, t1. If neither t0 nor t1 is positive,

// there were no intersection

In this simple ray-tracer, we only care about the intersection closest to the camera. E.g. if several of our batch of 8 spheres are intersected, we need to find the closest (positive) one. Then, we need to check the t against the closest global one, i.e. the value currently in currentMin archsimd.Float32x4 declared just outside the for-loop.

With scalar code, this was just a few simple if-statements for a single t0/t1 pair. With SIMD and 8+8 t0/t1, things become much more complicated.

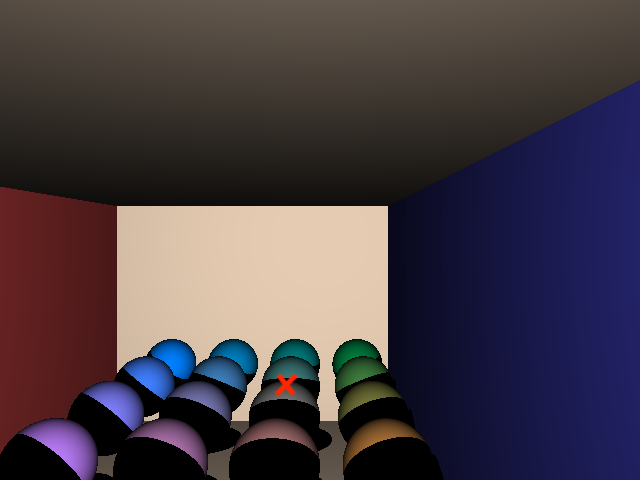

Let’s examine a ray cast at the red X in the below image:

The t0 and t1 values for the batch of 8 spheres being intersected (the two rightmost columns):

t0: [20.244858,16.751732,14.303255,NaN,NaN,NaN,NaN,NaN]

t1: [20.992985,18.744331,15.451029,NaN,NaN,NaN,NaN,NaN]

at a glance, we humans can easily see that 14.30 from t0’s third element is the closest one. However, for SIMD code, things aren’t that easy.

Also - what’s up with all those NaN (not-a-number)? Well, just before we have computed t0 and t1, our code does thcSqrt := thc.Sqrt() where we take the square root of each element in thc.thc in this case contains [0.1399231,0.99261475,0.3293457,-1.8499298,-7.3356323,-5.612915,-5.4062195,-6.715454], and as is established in mathematics, the square root of a negative number is undefined (unless bringing in imaginary numbers which is far out of scope and not necessary for this blog post). These NaNs will be masked off in our code since they indicate that no intersection takes place.

// t0: [20.244858,16.751732,14.303255,NaN,NaN,NaN,NaN,NaN]

// t1: [20.992985,18.744331,15.451029,NaN,NaN,NaN,NaN,NaN]

// t0 and t1 are the two intersection points on the sphere (typically enter and exit, but there are edge cases)

// We need to find the lowest positive t0 / t1

// Mask away negative values from both t0 and t1.

t0PosMask := zeroes.Less(t0) // [-1 -1 -1 0 0 0 0 0]

t1PosMask := zeroes.Less(t1) // [-1 -1 -1 0 0 0 0 0]

t0Pos := t0.Masked(t0PosMask) // [20.244858,16.751732,14.303255,0,0,0,0,0] (NaNs replaced by 0)

t1Pos := t1.Masked(t1PosMask) // [20.992985,18.744331,15.451029,0,0,0,0,0] (NaNs replaced by 0)

// Find min-values lane-wise for t0 and t1

minT := t0Pos.Min(t1Pos) // [20.244858,16.751732,14.303255,0,0,0,0,0]

// Create a mask we can use to only keep positive minT values

positiveTMask := minT.Greater(zeroes)

// If no element is greater than zero, we can skip since there were no intersection.

if positiveTMask.ToInt32x8().IsZero() {

continue

}

// Get rid of zeroes in minT, do a masked merge, turning elements where mask is false to float32 max value.

// maxT is a Float32x8 having had 3.4028235e38 (max float32) broadcasted to it

minT = minT.Merge(maxT, positiveTMask) // [20.244858,16.751732,14.303255,1e38,1e38,1e38,1e38,1e38]

// Now, we need to find the smallest non-zero element in minT. I.e. a "horizontal min".

// Split our 8 elements into two four-element halves and call element-wise min. This results

// in the 4 lowest of the 8 elements being retained.

hi := minT.GetHi()

lo := minT.GetLo()

tX := hi.Min(lo) // min( [20.244858,16.751732,14.303255,1e38], [1e38,1e38,1e38,1e38]) => [20.244858,16.751732,14.303255,1e38]

// Next, we need to combine shuffling with more Min-calls, i.e. "rotating" the elements sideways,

// performing a new min call per iteration so we after three "rotations" have checked all elements

// against each other and the resulting min-value is present in all 4 elements.

// min( [20.244858,16.751732,14.303255, max],

// [16.751732,14.303255,max, 20.244858])

// => [16.751732,14.303255,14.303255, 20.244858]

//

// min( [16.751732,14.303255,14.303255, 20.244858],

// [14.303255, 20.244858,16.751732,14.303255]

// => [14.303255, 14.303255,14.303255,14.303255]

//

// At this point, we see that the lowest value is present in all elements. In practice, depending on the data in

// the lanes, an additional shift could be necessary, so in practice we always perform three min/shift operations.

tX = tX.Min(tX.SelectFromPair(1, 2, 3, 0, tX)) // min( [5,1,6,3], [3,5,1,6]) => [3,1,1,3]

tX = tX.Min(tX.SelectFromPair(2, 3, 0, 1, tX)) // min( [3,1,1,3], [3,3,1,1]) => [3,1,1,1]

tX = tX.Min(tX.SelectFromPair(3, 0, 1, 2, tX)) // min( [3,1,1,1], [1,3,1,1]) => [1,1,1,1]

// Check if this iteration's min is less than the GLOBAL existing one. If not, we can skip

// running the semi-expensive code figuring out which sphere index we've

// intersected as closest. The mask below works since we always have the _same_ four values in currentMin and tX

msk := currentMin.Less(tX).ToInt32x4()

if !msk.IsZero() {

continue

}

// Current iteration has produced the lowest T (distance to intersection) yet. Assign tX to currentMin.

currentMin = tX

That was complex! Indeed, something as simple as “find the lowest value in an 8-element vector” is (as far as I’ve figured things out) actually a rather complex operation.

Of course, it’s certainly possible to Store the elements back to a regular [8]float32 and then find the lowest value using a for-loop, or the built-in min function. However, it seems as performance takes a significant hit when switching to/from SIMD and ordinary code. A very complex topic, my knowledge of CPU superscalarity, branch prediction and cache lines is limited, but my - albeit limited - empirical observations does strongly indicate that Go SIMD code performs best when full algorithms (such as a ray-sphere intersection) are implemented only using SIMD instructions. We do have a few if-statements to facilitate “exit early” scenarios, which needs to be balanced against the cost of running unnecessary code (i.e. when you already know that the ray will miss all spheres in the batch).

The final step of the intersection algorithm is to figure out which sphere that was intersected. Why do we need this information? Well, strictly speaking, we don’t always need it - but usually, intersected objects have material properties (color, reflectivity, transparency, textures etc), they could have pre-computed normals etc. which are not used in the intersection tests, but which plays an important role in the overall process of generating nice-looking ray-traced images.

The Go Gopher, created by Reneé French, ray-traced showcasing different materials, reflectivity etc.

Therefore, we need to figure out which sphere that was intersected. (Or in the case of the Gopher image above - rendered using one of my other toy ray-tracing projects - triangles loaded in groups from .OBJ files having different colors etc.

So, given an arbitrary 8-element vector such as [2,5,1,7,9,3,5,6], where we know that 1 is the lowest value (see section 4.5) - how do we know that the 1 sits at index 2? Again, using scalar code, we could use some for-loop with an if-statement, or something like slices.Index. However, since we really want to stay in the simd/archsimd domain - how do we accomplish this using SIMD code?

Again, the solution is rather complex and non-intuitive, involving masks and shuffles.

I’m quite certain one could accomplish this using other methods as well. Perhaps an AI coding agent could help out? However, since I’m writing these blog posts about Go SIMD in order to learn SIMD programming, I’d rather figure things out myself.

As stated above, we must know the value we’re after and if the vector contains the value more than once, the lowest occurring index will be returned.

We take advantage of already having the currentMin vector that has the lowest T in all 4 elements. By performing an element-wise Equal operation against the lo and hi parts containing the element-wise t values, we can produce a mask indicating which element from 0-7 that matches the computed min T.

Example: Given a known currentMin containing let’s say [2,2,2,2] and an 8-element vector [3,4,2,5,8,3,5,7], we start by splitting into the lo and hi parts.

lo: [3,4,2,5] hi: [8,3,5,7]

Next, we produce Equal masks for the lo and hi parts:

[3,4,2,5] == [2,2,2,2] => [0,0,-1,0]

[8,3,5,7] == [2,2,2,2] => [0,0,0,0]

Now we have the two masks [0,0,-1,0], [0,0,0,0]. How do we figure out that it is index 2 that’s set? Shuffling!

At the time of writing this blog post, a CL had just been submitted that added

ToBits()methods to thearchsimdAPI. For example,Mask32x8.ToBits()should return anuint8we can do normal Go bit tricks on to determine which bit that’s set. However, using the newToBitsmethods will have to wait a little bit (pun intended) more.

What do I mean by shuffling in this case? The trick here is to shift all elements left and then check if the mask equals [-1,0,0,0]. By keeping track of the number of times we’ve shifted, we know which index that was set.

The Go code below uses a normal for-loop for brevity, but is slightly faster with manual loop-unrolling:

func resolveCurrentIndex(maskLo archsimd.Int32x4, maskHi archsimd.Int32x4, offset, currentIndex int) int {

for i := range 4 {

// firstElemSetMask is declared elsewhere as [-1,0,0,0]

// If XOR produces [0,0,0,0] the masks are equal.

if maskLo.Xor(firstElemSetMask).IsZero() {

// If the lower mask is equal, return the iteration index i + the offset (e.g. which batch of 8).

return offset + i

}

if maskHi.Xor(firstElemSetMask).IsZero() {

return offset + 4 + i

}

// shift every element one step to the left, e.g. [0,0,1,0] => [0,1,0,0],

// next time [0,1,0,0] becomes [1,0,0,0] and so on.

maskLo = maskLo.PermuteScalars(1, 2, 3, 0)

maskHi = maskHi.PermuteScalars(1, 2, 3, 0)

}

// If no elem was set, return the index passed to this func

return currentIndex

}

With this piece of code, we can finally finish our IntersectSpheresSIMD for-loop and return the results:

maskLo := currentMin.Equal(lo).ToInt32x4() // Might produce [0,0,1,0]

maskHi := currentMin.Equal(hi).ToInt32x4() // [0,0,0,0]

// Finally, figure out _which_ index in the mask(s) that has value 1.

currentIndex = resolveCurrentIndex(maskLo, maskHi, i, currentIndex)

}

// Extract scalar value for the tMin.

tMin := currentMin.GetElem(0)

return tMin, currentIndex, currentIndex != -1

That was a long section! As seen, the upper part of the IntersectSpheresSIMD function dealt with loading sphere and ray data into SIMD registers, and then we more-or-less implemented the scalar version of the code using simd/archsimd but for 8 spheres at a time. Key differences were using masks where possible to avoid if-statements and finally we had to use some quite peculiar code to figure out the min value and at what index it had in the overall Spheres struct.

All this work and added complexity hopefully yields some nice performance improvement. In essence, we are getting x8 more work done per iteration, albeit using various vector instructions, than the scalar version. However, picking out the min value and its index for each iteration is much more complex than just having variables declared outside the for-loop, so we shouldn’t expect 8x the performance. Let’s dive into the numbers!

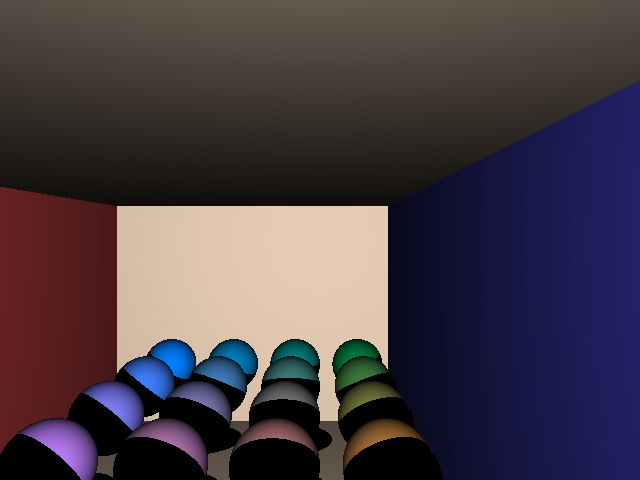

As benchmark scenario, I’m intersecting the same 16 spheres as seen in this scene.

The benchmark functions are very simple:

func Benchmark16IntersectSpheresSIMD(b *testing.B) {

ray := &std.Ray{

Orig: &std.Vec4{3, 4, 20, 0},

Dir: &std.Vec4{-0.16645914, -0.24594483, -0.95488346, 0},

}

spheres := AsStructOfArrays(std.SixteenSpheres())

for b.Loop() {

// Note that for some reason, these calls are NOT optimized away.

_, _, _ = IntersectSpheresSIMD(ray, spheres) // Just using the non-SIMD version here instead in the other benchmark.

}

}

Results!

Benchmark16IntersectSpheres-16 12671766 107.0 ns/op

Benchmark16IntersectSpheresSIMD-16 51934014 23.33 ns/op

In this particular scenario, the SIMD version is ~4.5x times faster than the scalar code! A very good improvement, indeed!

Back in part 2 of this blog post, I tried accelerating the scalar version doing ray/sphere intersections by using SIMD code for the dot products. That failed miserably, with the SIMD version needing about 3x the time of the plain Go one.

If we revisit those same benchmark, but do them using the same 16 spheres as benchmarked above, the results are as follows, with the “old” implementations marked as “Part2”:

Benchmark16Part2IntersectSpheres-16 12821304 93.85 ns/op

Benchmark16Part2IntersectSpheresSIMD-16 4369584 276.9 ns/op

Benchmark16IntersectSpheres-16 12671766 107.0 ns/op

Benchmark16IntersectSpheresSIMD-16 51934014 23.33 ns/op

The old plain Go implementation is actually a bit faster than the new plain Go one, the difference being that the old one does NOT use “vertically aligned data”, which isn’t advantageous in that context.

However, the difference between our brand new fully-SIMD optimized Benchmark16IntersectSpheresSIMD and the old “hybrid” Benchmark16Part2IntersectSpheresSIMD is massive - more than 10x in favor of the new one! Sure, the “hybrid” one only used SIMD for the dot products, which we now know introduced a severe performance regression.

While this is an anecdotal observation from my part - writing one’s SIMD code “fully” SIMD in regard to the following bullets really does seem to affect performance greatly:

As an experiment, I stripped out the complex SIMD code for finding the current “min” value and index. I won’t be posting the full code, but in essence, just Store back into a normal Go array and then use a for-loop and variables declared outside the for-loop to check if a new lowest t has been found and its index.

// Store minT into a normal Go *[8]float32 declared outside the loop

minT.Store(tStored)

// Iterate over all values from minT, find the lowest positive hit.

for idx, tt := range tStored {

if tt > 0 && tt < currentMinT {

// If a new lowest hit is found, update the min t and index declared outside the loop.

currentMinT = tt

currentIndex = i + idx

}

}

The result:

Benchmark16IntersectSpheresSIMD-16 49858376 24.42 ns/op

Benchmark16IntersectSpheresSIMDMinIndexScalar-16 42706900 25.92 ns/op

The IntersectSpheresSIMDMinIndexScalar version which is way less complex only performs a few percent (~1.5 ns) slower. Unless we’re after the absolutely max performance, one could argue that the code complexity trade-off of the “pure SIMD implementation” just isn’t worth it.

Note though that once archsimd gets support for ToBits() we might be able to do better, and it’s also quite likely there are much better ways to find min/index than the shuffle-and-mask heavy approach I’ve used.

The image we’ve seen above with 5 planes and 16 spheres can be rendered using both SIMD and non-SIMD code paths. Note that I’ve implemented pure-SIMD accelerated ray/plane intersection code as well as a special form of the ray-sphere intersection for casting shadow rays. With shadow rays, we don’t care about min t or indexes, we just need to know whether something obstructed a ray from an intersection point to a point light. The point light is in the upper right corner of the image, but isn’t rendered in any way.

Plain Go: 164.483787ms

SIMD: 38.361375ms

The scene / functionality is very simple as far as ray-tracers go, but we do see more than 4x the performance using the variant where the renderer uses the fully SIMD accelerated intersection functions.

This was a long one! I think that this wraps up the series on Go SIMD, at least until 1.26 is out. Perhaps I’ll delve into adding more features (reflection, refraction, models, SIMD-accelerated BVH trees) and/or perhaps turn it into a path-tracer with multi-core support etc. We’ll see! It’s been great fun writing these blog posts and learning Go SIMD.

Until next time!