Blogg

Här finns tekniska artiklar, presentationer och nyheter om arkitektur och systemutveckling. Håll dig uppdaterad, följ oss på LinkedIn

Här finns tekniska artiklar, presentationer och nyheter om arkitektur och systemutveckling. Håll dig uppdaterad, följ oss på LinkedIn

Recently, a proposal for adding low-level SIMD support to Go was “Accepted”. In the last part took a look at SIMD for dot product computations in order to speed up ray-sphere intersection testing. In this blog post, it’s time to “think in SIMD” to hopefully make better use of SIMD.

What does one mean by “Thinking in SIMD”? I didn’t coin that term myself, I’ve seen it both in this essay and in a similarly named Youtube series. That said, I’ll try to provide my own layman’s version of “thinking in SIMD”.

My take might boil down to a few principles:

Note that the latter two bullets will be revisited in more detail in follow-up blog posts.

Note: Everything in this blog post deals with data-parallelism using SIMD. It does NOT deal with thread/core concurrency, everything happens on a single CPU core, though it’s certainly possible to run SIMD code on many cores simultaneously.

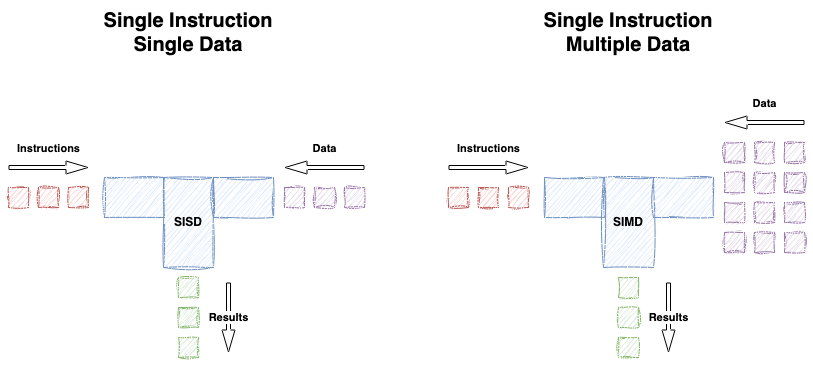

Remember, SIMD is basically about applying the same instruction to multiple data elements:

In December 2025, Go 1.26 RC1 was released including the simd experiment. An important change from previous iterations was renaming of the simd package to simd/archsimd, see github issue.

This change is reflected in the source code examples throughout this blog post.

First and foremost, one should pay particular attention to the nature of working with vectors in SIMD. A vector is typically a series of numeric values of a given type such as float32. In Go, a []float32 can be used as a variable-length vector, while a [4]float32 could represent a 4-element vector. With the simd experiment, a 4-element float32 vector is represented as the type archsimd.Float32x4.

With SIMD CPU extensions such as SSE, AVX, AVX2 and AVX512, or NEON on ARM CPUs, most vector operations work in an element-wise fashion. Here, we see a simple vec1 x vec2 multiplication of two 4-element vectors:

[2, 4, 6, 8]

[1, 3, 5, 7] x (multiply)

---------------

[2, 12, 30, 56]

E.g. given the two 4-element vectors above, a multiplication results in elements in the same column being multiplied by each other, with the result stored in the corresponding column (or index) of the result vector.

In Go simd code, this corresponds to:

v1 := archsimd.LoadFloat32x4Slice([]float32{2, 4, 6, 8})

v2 := archsimd.LoadFloat32x4Slice([]float32{1, 3, 5, 7})

result := v1.Mul(v2) // [2, 12, 30, 56]

In the example above, we multiplied two vectors with each other.

However, what if the problem we are trying to solve is dependent on data within the same vector? A really simple example could be calculating the sum of all elements. Dot products, as explored in my last blog post is another.

Let’s say we want to sum all elements of the 8-element int32 vector [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8] using SIMD. This is actually somewhat tricky, involving a series of horizontal additions, archsimd.AddPairs in Go simd terms:

func SumInt32SIMD(v *[8]int32) int32 {

elems := archsimd.LoadInt32x8(v) // [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]

lo := elems.GetLo() // [1,2,3,4]

hi := elems.GetHi() // [5,6,7,8]

lo = lo.AddPairs(lo) // [3,7,3,7]

lo = lo.AddPairs(lo) // [10,10,10,10]

hi = hi.AddPairs(hi) // [11,15,11,15]

hi = hi.AddPairs(hi) // [26,26,26,26]

return lo.GetElem(0) + hi.GetElem(0) // 10 + 26 = 36

}

What if you would like to multiply all elements? Or find the min/max value? Inter-vector operations are MUCH trickier than operations across different vectors. For example, there is no multiplication variant of AddPairs.

For a summing multiplication, we must restructure our data - which will also make it much more suitable for data parallelism. But more on that later. How to multiply all elements in a vector?

func SumMul(v *[8]int32) int32 {

elems := archsimd.LoadInt32x8(v) // [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]

lo := elems.GetLo() // [1,2,3,4]

hi := elems.GetHi() // [5,6,7,8]

tmp := lo.Mul(hi) // [1*5, 2*6, 3*7, 4*8]

return tmp.GetElem(0) * tmp.GetElem(1) * tmp.GetElem(2) * tmp.GetElem(3) // 6 * 12 * 21 * 32

}

This solution is quite good and efficient. But if you’d want to do the same operation for many vectors at the same time?

Under a make-believe circumstance where we want to do this multiply operation on 8 vectors instead of one, it could be beneficial to instead represent the data in a “column-major” format where we have eight vectors each having eight elements:

[1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

[2, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

[3, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

[4, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

[5, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

[6, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

[7, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

[8, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

Code:

func SumMulVerticalSIMDArrays(e1, e2, e3, e4, e5, e6, e7, e8 *[8]int32) int32 {

v1 := archsimd.LoadInt32x8(e1)

v2 := archsimd.LoadInt32x8(e2)

v3 := archsimd.LoadInt32x8(e3)

v4 := archsimd.LoadInt32x8(e4)

v5 := archsimd.LoadInt32x8(e5)

v6 := archsimd.LoadInt32x8(e6)

v7 := archsimd.LoadInt32x8(e7)

v8 := archsimd.LoadInt32x8(e8)

return v1.Mul(v2).Mul(v3).Mul(v4).

Mul(v5).Mul(v6).Mul(v7).Mul(v8).

GetLo().

GetElem(0)

}

Benchmarking these two multiply-sum methods produces the following numbers:

BenchmarkSumMul-16 617426278 1.988 ns/op 0 B/op 0 allocs/op

BenchmarkSumMulVerticalArrays-16 333935000 3.618 ns/op 0 B/op 0 allocs/op

The first option which used a combination of GetLo, GetHi, Mul and GetElem is almost twice as fast as the latter option using “vertical” data, probably due to having to do eight archsimd.LoadInt32x8 per iteration.

Here’s the “eureka!” moment! We are only using one of the SIMD lanes in the “vertical” option! For basically no extra cost, if we have structured our data properly, we can do eight of these multiplications for the price of one.

Given these two benchmark functions, where the first performs 8 separate SumMul and the latter uses SumMulVerticalSIMDArrays which can do all of them in one go:

func BenchmarkSumMul8(b *testing.B) {

v := &[8]int32{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8}

for b.Loop() {

S = SumMul(v)

S = SumMul(v)

S = SumMul(v)

S = SumMul(v)

S = SumMul(v)

S = SumMul(v)

S = SumMul(v)

S = SumMul(v)

}

}

func BenchmarkSumMulVerticalArrays8(b *testing.B) {

// Using the same data everywhere since I'm feeling lazy.

e1 := &[8]int32{1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1}

e2 := &[8]int32{2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2}

e3 := &[8]int32{3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3}

e4 := &[8]int32{4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4}

e5 := &[8]int32{5, 5, 5, 5, 5, 5, 5, 5}

e6 := &[8]int32{6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6}

e7 := &[8]int32{7, 7, 7, 7, 7, 7, 7, 7}

e8 := &[8]int32{8, 8, 8, 8, 8, 8, 8, 8}

for b.Loop() {

S = SumMulVerticalSIMDArrays(e1, e2, e3, e4, e5, e6, e7, e8)

}

}

The results:

BenchmarkSumMul8-16 84558235 14.27 ns/op

BenchmarkSumMulVerticalArrays8-16 327685940 3.680 ns/op

Performance wise, the numbers are now very much in favor of the “vertical” solution. (Note though that the results may sit in a archsimd.Int32x8 which we either need to Store back into memory or use GetElem to get to the actual values which may incur a slight performance penalty).

What I’ve been trying to showcase here is that data structuring matters and different use-cases requires different strategies.

When doing ray-tracing, there are definitely some low-hanging fruits to pick when it comes to speeding up rendering using SIMD techniques.

When we’re dealing with 3D graphics and ray-tracing, a lot of vectors and points in three-dimensional space are represented using their x,y and z axis coordinates. [0,0,0] is the origin, [2,1,0] is a point two units (right) along the X-axis, and one unit (up) along the Y-axis and so on. In many (note - not all!) cases we have no need for a fourth element. Even if we could stuff a 0 (for a Vector) or 1 (for a Point) into the fourth element (typically called w), it’s essentially 25% extra baggage.

However, we can also structure this data differently to allow for better data parallelism and possibly SIMD lane utilization.

With AVX2 we can handle 4 64-bit elements or 8 32-bit elements per vector register. A beneficial side effect of “vertical” data structuring is that if we only have three elements per vector, processing them using a “vertical” paradigm means that instead of wasting data lanes, we can fully saturate the lanes as long as we have 8 different vectors available to process. E.g:

3-element vectors (the vectors are [1,1,1], [2,2,2] and so on)

represented vertically

x: [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]

y: [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]

z: [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]

vs

Eight horizontal 3-element vectors using just the first three columns.

x,y,z

[1,1,1,0,0,0,0,0]

[2,2,2,0,0,0,0,0]

... omitted ...

[8,8,8,0,0,0,0,0]

As clearly seen, in the case of [x,y,z] 3-element vectors, using a 256-bit wide SIMD register per vector wastes 5 of out 8 lanes!

If we consider dot products, things starts to become interesting. Remember, a dot product for a 4-element vector is x1*x2 + y1*y2 + z1*z2 + w1*w2.

In the last part, we tried to use SIMD for single dot products, which yielded very good results in isolated dot product benchmarks, but actually worsened performance when applied in the context of dot products in ray/sphere intersection tests. The underlying reason proved elusive, though subsequent work strongly indicates that sequential instructions using SIMD works MUCH better than mixing pure scalar code with SIMD on line-to-line basis. More on that later.

As a recap, the code for a single SIMD dot product of 4-element vectors, is actually quite similar to the same-vector multiplications from section 2:

func DotProductSIMDSlice(v1, v2 []float32) float32 {

r1 := archsimd.LoadFloat32x4Slice(v1) // [2, 3, 4, 5]

r2 := archsimd.LoadFloat32x4Slice(v2) // [3, 4, 5, 6]

sumdst := archsimd.Float32x4{}

sumdst = r1.MulAdd(r2, sumdst) // => [6,12,20,30]

sumdst = sumdst.AddPairs(sumdst) // => [18,50,18,50]

sumdst = sumdst.AddPairs(sumdst) // => [68,68,68,68]

return sumdst.GetElem(zero)

}

However, given 8 lanes with AVX2 for float32s, if we structure 16 vectors (remember, two vectors per dot product) vertically, we can perform 8 dot products using data-parallelism!

Note that the dot products below are computed per corresponding column, e.g. x[n]*x2[n] + y[n]*y2[n] + z[n]*z2[n] + w[n]*w2[n]

// 8 logical 4-element vectors represented column-wise

x := archsimd.LoadFloat32x8Slice([]float32{1,2,11,12,22,44,66,88})

y := archsimd.LoadFloat32x8Slice([]float32{3,4,13,14,22,44,66,88})

z := archsimd.LoadFloat32x8Slice([]float32{5,6,15,16,22,44,66,88})

w := archsimd.LoadFloat32x8Slice([]float32{7,8,17,18, 22,44,66,88})

// 8 other logical 4-element vectors represented column-wise

x2 := archsimd.LoadFloat32x8Slice([]float32{11,12,111,112,122,144,166,188})

y2 := archsimd.LoadFloat32x8Slice([]float32{13,14,113,114,122,144,166,188})

z2 := archsimd.LoadFloat32x8Slice([]float32{15,16,115,116,122,144,166,188})

w2 := archsimd.LoadFloat32x8Slice([]float32{17,18,117,118,122,144,166,188})

dotProducts := x.Mul(x2). // All eight x*x2 in one go

Add(y.Mul(y2)).

Add(z.Mul(z2)).

Add(w.Mul(w2))

The dotProducts variable now contains element-wise dot products for each “lane”: [244,320,6404,6920,10736,25344,43824,66176].

(One can also use

MulAddfor a fused multiply-add using fewer instructions, though the Go compiler may very well detect sequential multiply and adds and generate the FMA instructions on its own. The benchmark difference between the two variants are negligible).

The same code written using plain Go. Note that conceptually, index n in the loop could be thought of as the SIMD lane. Only that with SIMD code, we don’t need an index since all lanes are processed in parallel. This is a good example of “standard programming” vs “SIMD thinking”.

x := []float32{1, 2, 11, 12, 22, 44, 66, 88}

y := []float32{3, 4, 13, 14, 22, 44, 66, 88}

z := []float32{5, 6, 15, 16, 22, 44, 66, 88}

w := []float32{7, 8, 17, 18, 22, 44, 66, 88}

x2 := []float32{11, 12, 111, 112, 122, 144, 166, 188}

y2 := []float32{13, 14, 113, 114, 122, 144, 166, 188}

z2 := []float32{15, 16, 115, 116, 122, 144, 166, 188}

w2 := []float32{17, 18, 117, 118, 122, 144, 166, 188}

dotProducts := make([]float32, 8)

for n := range 8 {

dotProducts[n] = x[n]*x2[n] + y[n]*y2[n] + z[n]*z2[n] + w[n]*w2[n]

}

Yes, in all essence - what we’re doing is basically replacing the sequential for-statement with SIMD able to perform the same work in one go.

Note that using this SIMD solution, all results goes directly into the archsimd.Float32x8 results variable. No need to use the horizontally adding AddPairs etc. to obtain the result.

Time for some benchmarking!

Note: Something has happened with Go 1.26RC1 that causes the Go compiler to (at least sometimes) optimize away calls inside

for b.Loop()whose results are assigned to_. I have had to rely on assigning to exported package-scoped variables in order to get sensible results, which clutters the benchmark code somewhat.

This time we’ll focus on data parallelism for dot products, 8 at a time to reflect a “best-case” scenario för AVX2.

Four scenarios:

By “horizontal”, I refer to two 4-element logical vectors organized row-wise into a single physical vector as [8]float32 or archsimd.Float32x8.

By “vertical”, I refer to 8-element logical vectors organized column-wise, e.g. all X-coords goes into a single [8]float32 or archsimd.Float32x8 and so on.

Each iteration of b.Loop() will perform eight dot products.

The benchmark code for the SIMD benchmarks:

func BenchmarkDotSIMDHorizontal(b *testing.B) {

// Provides 8 slices of test vectors.

v1, v2, v3, v4, v5, v6, v7, v8 := testVectorsHorizontal()

// Load vectors into SIMD registers

v1Simd := archsimd.LoadFloat32x8Slice(v1)

v2Simd := archsimd.LoadFloat32x8Slice(v2)

v3Simd := archsimd.LoadFloat32x8Slice(v3)

v4Simd := archsimd.LoadFloat32x8Slice(v4)

v5Simd := archsimd.LoadFloat32x8Slice(v5)

v6Simd := archsimd.LoadFloat32x8Slice(v6)

v7Simd := archsimd.LoadFloat32x8Slice(v7)

v8Simd := archsimd.LoadFloat32x8Slice(v8)

// tot variable needed to avoid compiler optimizing away work inside benchmark loop

tot := float32(0.0)

for b.Loop() {

// Each call to DotProductSIMD2x4FromFloat32x8 performs 2 dot products from the

// [1,2,3,4, 5,6,7,8] dot [1,2,3,4, 5,6,7,8] four 4-element vectors stuffed

// inside the two Float32x8's.

a, b := std.DotProductSIMD2x4FromFloat32x8(v1Simd, v2Simd)

c, d := std.DotProductSIMD2x4FromFloat32x8(v3Simd, v4Simd)

e, f := std.DotProductSIMD2x4FromFloat32x8(v5Simd, v6Simd)

g, h := std.DotProductSIMD2x4FromFloat32x8(v7Simd, v8Simd)

tot += a + b + c + d + e + f + g + h // arbitrary work to avoid compiler optimizing away the calls above.

}

}

The vertical one:

func BenchmarkDotSIMDVertical(b *testing.B) {

// convenience, returns ready-to-use Float32x8 vertical vectors.

x1, y1, z1, w1, x2, y2, z2, w2 := testSIMDVectors()

sums := [8]float32{}

// tot variable needed to avoid compiler optimizing away work inside benchmark loop

tot := float32(0)

for b.Loop() {

// DotProductSIMD8 performs 8 dot products (one per lane) given the 16 input vectors

dots := DotProductSIMD8(x1, y1, z1, w1, x2, y2, z2, w2)

dots.Store(&sums)

// arbitrary work to avoid compiler optimizing away the calls above.

tot += sums[0] + sums[1] + sums[2] + sums[3] + sums[4] + sums[5] + sums[6] + sums[7]

}

}

Produced using $ GOEXPERIMENT=simd go1.26rc1 test -bench BenchmarkDot

BenchmarkDotPlainGoHorizontal-16 97503447 34.09 ns/op

BenchmarkDotPlainGoVertical-16 33211179 34.49 ns/op

BenchmarkDotSIMDHorizontal-16 212989243 5.578 ns/op

BenchmarkDotSIMDVertical-16 429010626 2.767 ns/op

That’s interesting! First off, we see that the for-loop based benchmarks perform almost identically, requiring ~34 ns to perform 8 dot products. I.e. restructuring the data here basically just adds complexity for no measurable gain.

Next, BenchmarkDotSIMDHorizontal which does 2 dot products per iteration (four calls per b.Loop()) performs MUCH better at ~5.5ns/op. Even so, switching to vertically aligned data for 8 dot products doubles the performance, allowing a whopping 8 dot products to be performed in just ~2.7 ns.

Note that part of the advantage of BenchmarkDotSIMDVertical may be due to less function-call overhead.

What we saw above with the vertically aligned dot products is a prime example of “sequential instructions for data-parallelism”.

Instead of the slightly contrived MulAdd + AddPairs dot product over two horizontal vectors, we could use the exact same x*x2 + y*y2 + z*z2 + w*w2 used in plain Go, represented as chained x.Mul(x2).Add(y.Mul(y2)..., for the SIMD vertical solution - the key difference being that the SIMD variant can do 8 dot products (given AVX2) at the same time.

This is a prime example of applying an ordinary algorithm across many data lanes, yielding sometimes huge performance improvements.

In the next blog post, we’ll return to our ray/sphere intersection code, and will try to transform it from intersecting one ray with one sphere, into intersecting one ray with eight spheres, given the data parallelization techniques touched upon in this blog post.

Until next time!