Blogg

Här finns tekniska artiklar, presentationer och nyheter om arkitektur och systemutveckling. Håll dig uppdaterad, följ oss på LinkedIn

Här finns tekniska artiklar, presentationer och nyheter om arkitektur och systemutveckling. Håll dig uppdaterad, följ oss på LinkedIn

In part 1 of this two part blog, we developed a simple webcomponent using only plain javascript, css and html. In this second part we will explore how the stencil.js toolchain can help us author components and ease integration in some of today’s popular frameworks.

As we could see in our simple accordion example in part 1, writing components using vanilla js and native DOM APIs is not very efficient. For example, we had to manually register and de-register event handlers and make sure changes to attributes and state are reflected in the components DOM representation. We have none of the things we nowadays take for granted using a framework. I’ve chosen to take a look at stencil.js that originates from the team behind ionic. As they themselves describes it:

Stencil is a toolchain for building reusable, scalable Design Systems. Generate small, blazing fast, and 100% standards based Web Components that run in every browser.

By using popular concepts from leading frameworks and libraries they promise a much nicer developer experience with features like Virtual DOM, Reactive data-binding, Typescript, JSX (for the templating part), test support and more. They explicitly target it to be used for building entire Design Systems, but you can of course use it to build a smaller scale component library. An important feature is that the output of the stencil compiler is plain javascript with no runtime dependencies and therefore a very small footprint.

Like other popular libraries stencil has a CLI for scaffolding your projects. Simply run:

npm init stencil

and choose “component” for a simple starter project type. By default, some files for a sample component “my-component” is generated that shows the basic features. (you create additional components by running npm run generate)

You will get a number of files generated:

my-component.css

Here you define you styles. It’s very easy to add support for scss if you prefer that.

my-component.tsx

The actual component with its JSX and code.

By default you also get unit and e2e test skeletons that you can update as you progress:

For comparison I’ve chosen to implement the acme-accordion component that we developed earlier using vanilla js. Here’s how a corresponding implementation could look like using stencil.js:

import {Component, h, Host, Prop, State} from '@stencil/core'

@Component({

tag: 'acme-accordion',

styleUrl: 'acme-accordion.scss',

shadow: true,

})

export class AcmeAccordion {

@Prop() headerText: string

@State() open: boolean

render() {

return (

<Host>

<header class={this.open ? 'open' : ''} onClick={() => this.open = !this.open}>{this.headerText}</header>

<section>

<slot></slot>

</section>

</Host>

)

}

}

That’s a lot less code compared to the native version and in my opinion a lot easier to read!

Like some other frameworks, Stencil uses decorators to abstract boilerplate code and JSX to define the template. If you have some familiarity with modern js frameworks you probably already recognize and understand most of what’s going on here:

The @Component is used to define some metadata about the component, its tag name, which style file(s) to use and whether it should render using shadow DOM or not.

The AcmeAccordion class also has some helping decorators. @Prop that tells us this is an attribute that the component depends on for its logic. Any changes to the attribute (from the outside) will cause the component to re-render. It roughly corresponds to the static observedAttributes() array in the native version.

@State which simply denotes an internal state (inaccessible to the outside) that we want to use in the component - in this example we want to track if the accordion is open or not. As for props, changes to a state variable will trigger re-rendering.

The render() function itself should be very familiar to any react developer as it’s using JSX syntax.

During the build, Stencil’s compiler will transform this into plain js that has no external dependencies. The resulting component library module can be published to a repository like NPM and easily added as any other dependency in your app.

To evaluate stencil.js I wanted to create a component at bit more fun and complex than the accordion component.

The imagined scenario is that ACME Inc has an shopping site network where different parts of the sites are developed using different tech-stacks (react, vue, angular). To keep things consistent and to avoid having to create and maintain different implementations of a frequently used “product view” component, we will create a custom component for this and then use it across the sites. The data model for an ACME product is something like this:

Beside presentation, the component should also have a “Add to cart” button. Clicking it should emit a “addToCart” event with the product’s pid as payload. The react/vue/angular components using the product view component can then listen this event to update a shopping cart or similar.

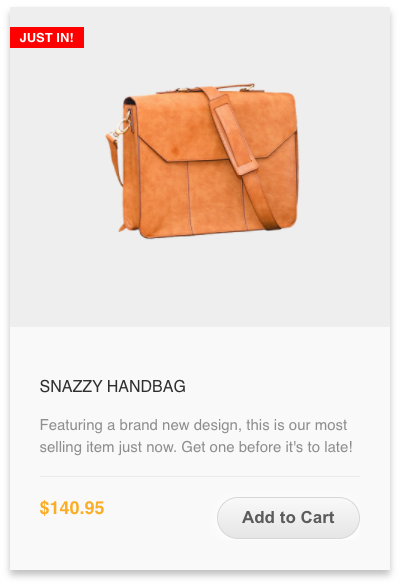

This is what the design team at ACME Inc came up with:

Using stencil’s generate command, we add the new “acme-product-card” component and implement it.

import {Component, Event, EventEmitter, h, Host, Prop} from '@stencil/core';

@Component({

tag: 'acme-product-card',

styleUrl: 'acme-product-card.scss',

shadow: true,

})

export class AcmeProductCard {

@Prop() pid: string;

@Prop() name: string;

@Prop() desc: string;

@Prop() imageSrc: string;

@Prop() price: number;

@Prop() badge: string;

@Event() addToCart: EventEmitter<string>;

render() {

const {pid, name, desc, imageSrc, price, badge, addToCart} = this;

return (

<Host>

<div class="card">

{badge && <div class="badge">{badge}</div>}

<div class="tumb">

<img src={imageSrc} alt=""></img>

</div>

<div class="details">

<h4>{name}</h4>

<p>{desc}</p>

<div class="bottom-details">

<div class="price">${price}</div>

<div class="actions">

<button onClick={() => addToCart.emit(pid)}>Add to Cart</button>

</div>

</div>

</div>

</div>

</Host>

);

}

}

It has properties matching the product data model and also uses another stencil decorator @Event() which enables us to conveniently emit events from our component.

As you can see in the example, we define a separate @Prop for each attribute we want to use as input. If we had even more input data it might be cleaner to have one custom attribute matching the actual product model, but as HTML attributes only support basic primitive types like strings and numbers, we can’t do that. (You could hack your way around this by serializing a rich object to a JSON string but that’s not recommended for several reasons.)

Instead, you could use getter/setters or the @Method decorator to allow imperative manipulation of a element’s properties and behaviour, but that somewhat complicates the usage as you would need to invoke methods on the component instance itself:

document.querySelector('some-custom-component').setProductData(productData)

Google has listed some best practices on how to deal with these considerations.

Frameworks like Vue and Angular (but currently not react) can set values by their corresponding property instead of its attribute, but for the sake of this example I’m keeping it simple and use standard primitive HTML attributes in the component.

Ok, so now we have a (very) small component library which we now publish to NPM so that we can import it into our sample projects. The following examples have all been created using each framework’s “hello-world” starter instructions and a dependency to the acme-components-sample lib has been added to package.json.

Some setup is required for our custom component library to work. A suitable place to do this in a Vue app is in main.js

First we import the bootstrapping init functions that Stencil has created for us:

import { applyPolyfills, defineCustomElements } from "acme-components-sample/loader";

Then we need to tell Vue to ignore our custom tags (otherwise we’ll get some warnings in the console).

Vue.config.ignoredElements = [/acme-\w*/];

and finally, register our components.

applyPolyfills().then(() => {

defineCustomElements();

});

The generated defineCustomElements() function will take care of registration of all included components, so there’s no more setup to to even if the library contained many components.

The applyPolyfills() call can be omitted if you don’t need to support browsers without native support for Web Components features (such as our beloved IE11)

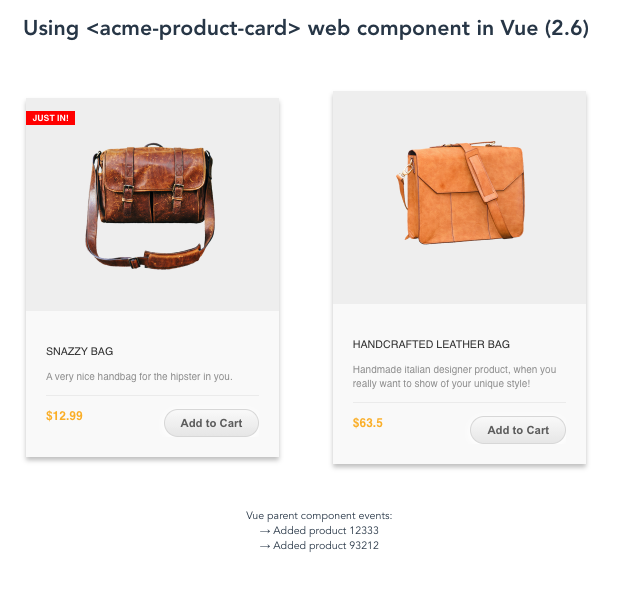

After this, the app can use the custom component like other native elements. To keep things simple, we’ll use some static mocked product data for a couple of products:

[{

"pid": "12333",

"badge": "Just in!",

"name": "Snazzy bag",

"desc": "A very nice handbag for the hipster in you.",

"imageSrc": "bag-1.png",

"price": "12.99"

}, {

"pid": "93212",

"name": "Handcrafted leather bag",

"desc": "Handmade italian designer product, when you really want to show of your unique style!",

"imageSrc": "bag-2.png",

"price": "63.50"

}]

In any Vue component in the app we can now render the products with our component using standard Vue templating and binding syntax:

...

<h1>Using <acme-product-card> web component in Vue (2.6)</h1>

<div class="products">

<acme-product-card v-for="product in products"

:key="product.pid"

:pid="product.pid"

:price="product.price"

:badge="product.badge"

:name="product.name"

:desc="product.desc"

:image-src="product.imageSrc"

v-on:addToCart="addedToCart">

</acme-product-card>

...

To verify that the event handling works as intended - all sample applications stores and renders a message for each addToCart event received.

Rendered output after clicking each of the “Add to Cart” buttons. View full source.

The setup in Angular is very similar, the first requirement is that we need to inform angular that we’re using custom tag names (CUSTOM_ELEMENTS_SCHEMA) in our angular templates in app.module.ts

@NgModule({

declarations: [

AppComponent

],

imports: [

BrowserModule

],

providers: [],

bootstrap: [AppComponent],

schemas: [

CUSTOM_ELEMENTS_SCHEMA // Tells Angular we will have custom tags in our templates

]

})

Then in the apps main.ts we register the components:

import { defineCustomElements } from 'acme-components-sample/loader';

...

defineCustomElements();

Then we’re free to start using it in our angular component. (app.component.html)

<h1>Using <acme-product-card> web component in Angular (10.2)</h1>

<div class="product-list">

<acme-product-card *ngFor="let product of products"

[attr.pid]="product.pid"

[attr.badge]="product.badge"

[attr.name]="product.name"

[attr.desc]="product.desc"

[attr.image-src]="product.imageSrc"

[attr.price]="product.price"

(addToCart)="onAddToCart($event)">

</acme-product-card>

The template binding syntax in angular is not that intuitive in my opinion, and I also had to use the attr-prefix so that protractor locators could find the non-standard attributes when writing tests.

Again, very similar setup as for the other frameworks - we register the custom components in the apps index.js:

import { applyPolyfills, defineCustomElements } from 'acme-components-sample/loader';

...

applyPolyfills().then(() => {

defineCustomElements();

});

Because React implements its own synthetic event system, it (currently) cannot listen for DOM events coming from custom elements without the use of a workaround. One such workaround is to manually add/remove an event listener for the custom event:

import {PRODUCTS} from "./mock-products";

const App = () => {

const [events, setEvents] = useState([]);

const productCardListRef = useRef(null);

//Hook up event handling for the addToCart event dispatched by acme-product-card element

useEffect(() => {

const onAddToCard = event => setEvents(e => [...e, `Added product ${event.detail}`]);

const targetRef = productCardListRef.current;

targetRef.addEventListener('addToCart', onAddToCard);

return () => targetRef.removeEventListener('addToCart', onAddToCard)

}, []);

return (

<div className="App">

<h1>Using <acme-product-card> web component in React (17).</h1>

<div className="products" ref={productCardListRef}>

{PRODUCTS.map(p => <acme-product-card key={p.pid}

pid={p.pid}

badge={p.badge}

name={p.name}

desc={p.desc}

image-src={p.imageSrc}

price={p.price}

data-testid={`card-${p.pid}`}>

</acme-product-card>)}

</div>

<ul id="events">React parent component events:

{events.map((eventMsg, index) => <li key={index}> → {eventMsg} </li>)}

</ul>

</div>

);

};

If you made it this far you should have a better understanding of what Web Components are, and what you can do with them. To finish off this post, let’s revisit our initial questions.

Given today’s fragmented frontend landscape, who would not like to have a standard compliant, future-proof, well tested and dependency free library of custom elements that you can simply reuse when switching between frameworks and projects?

With major browser adoption finally a reality - I would say they are more relevant than ever!

Hopefully this post has given you some insights into how you can create and use them, either by using native DOM APIs or by leveraging the benefits of a tool like Stencil. There are of course several other alternatives, like Polymer’s LitElement and Slim.js.

Even Vue, Angular and React themselves have plugins that enables you to wrap their own component implementations and expose them as standard web components - kind of the inverse of what we did here. A big drawback with that approach is that you then have a dependency to that framework’s runtime when you use the components in another context.

Web Components won’t replace other frameworks, but rather complement them. As I’ve demonstrated here, the integration into various frameworks still have some quirks but is pretty straight forward. Developing a high-quality component library or perhaps even a full design system (like Material UI) certainly is a complex and expensive task and it’s not for everyone.

Investing in Web Components would likely pay off if you have a heterogeneous tech stack and need an efficient way to achieve more consistency and reuse in your frontend apps. It might be a good idea to start small, implementing some simple, but highly reusable “dumb” components to encapsulate branding, style or layouts to evaluate it before going all in. It’s also highly recommended that you use a tool like Stencil to develop components even though it’s always good to have a grasp of the underlying platform first.

All source code in this post can be found in the stencil-blog-demo github repository.

Some recommended resources I found useful when writing this post: