Blogg

Här finns tekniska artiklar, presentationer och nyheter om arkitektur och systemutveckling. Håll dig uppdaterad, följ oss på LinkedIn

Här finns tekniska artiklar, presentationer och nyheter om arkitektur och systemutveckling. Håll dig uppdaterad, följ oss på LinkedIn

Recently, a proposal for adding low-level SIMD support to Go was “Accepted”. In a previous blog post I covered the basics. In this blog post, it’s time to become more practical, looking at possibly accelerating ray-sphere intersections in a toy ray-tracer I’ve written by leveraging SIMD-acceleration of dot product computations abundant in ray tracing.

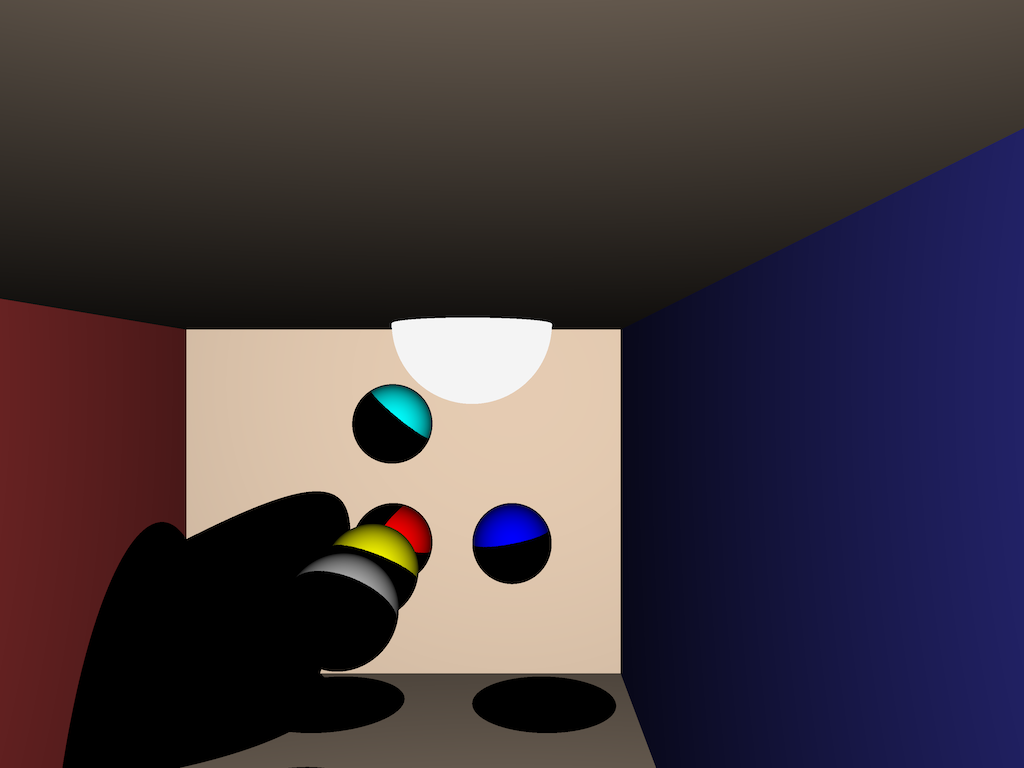

To see whether the new experimental SIMD package could offer performance improvements in hot code-paths, I decided to write a minimal ray-tracer supporting only spheres and planes, loosely based on code from scratchapixel.com. It’s not written to produce particularly good-looking results, it’s just a test-bed for trying out the SIMD optimizations we’re looking at:

I’ve done a bit of hobby ray- and path tracing in the past. While not the focus of this blog post, feel free to read some of my blogs on those topics. It’s great fun!

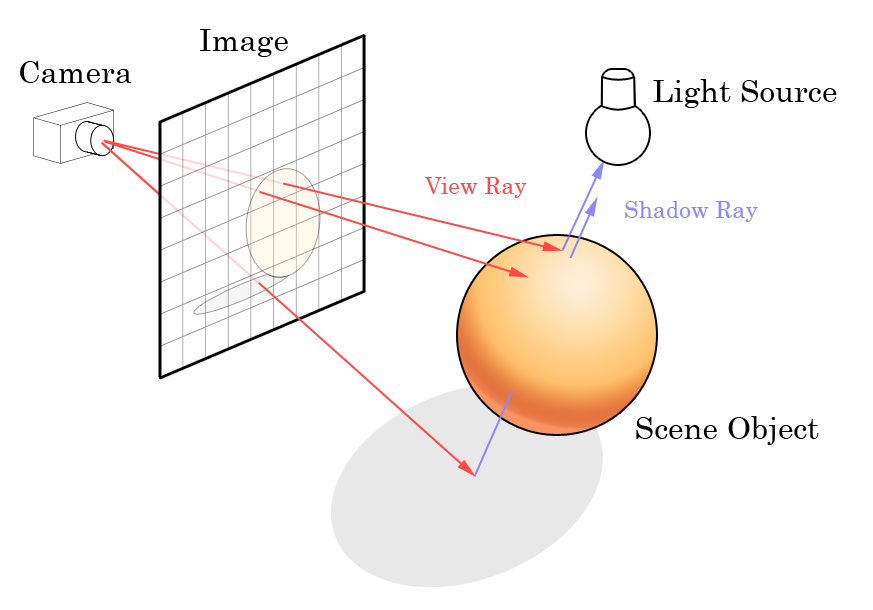

The most performance-critical parts of the ray tracer is performing intersection testing. For each pixel on an imaginary camera-plane, a ray is cast into the scene, and all intersections with spheres or planes are recorded, and the color of the closest intersected object is written (after some adjustments in regard to camera/object normal angles) to the output screen buffer.

Source: Wikipedia commons

The source code used in this blog post is available at https://github.com/eriklupander/simd-tracer.

Don’t take the code too seriously, it’s very much an ongoing experiment to figure out the Go SIMD package in the context of some really simple ray-tracing.

Remember - at the time of writing this blog post, the Go SIMD experiment needs

gotipinstalled with thedev.simdbranch downloaded. See this post from the SIMD proposal for installation details.

For a simple scene containing 5 planes and 7 spheres in 640x480 resolution, a total of almost four million ray-sphere intersection tests (including shadow rays) takes place. Baseline performance is ~38 ms for a full render (which includes writing the final pixel color’s RGBA components to an output bytes.Buffer).

The ray-sphere intersection code is not that complex. I based it on the geometric C++ solution from scratchapixel.

The full Go code:

func IntersectSphere(ray *Ray, center *Vec4, radiusSquared float32) (float32, bool) {

// Vector subtraction to get new vector from sphere center to ray origin

var L Vec4

sub2(center, ray.Orig, &L)

// Compute dot product of L and ray direction. If tca is negative, no intersection.

tca := L.dotProduct(ray.Dir)

if tca < 0 {

return 0.0, false

}

// Dot product of L with itself

lD := L.dotProduct(&L)

d2 := lD - tca*tca

// If larger than radius squared, no intersection

if d2 > radiusSquared {

return 0.0, false

}

// Compute distance to hit point.

thc := float32(math.Sqrt(float64(radiusSquared - d2)))

t0 := tca - thc

t1 := tca + thc

// Swap if t0 is greater than t1

if t0 > t1 {

tmp := t0

t0 = t1

t1 = tmp

}

// If t0 is negative, let's use t1 instead.

if t0 < 0 {

t0 = t1

}

// Both t0 and t1 are negative. No intersection.

if t0 < 0 {

return 0.0, false

}

return t0, true

}

The Vec4 type is just a type [4]float32 we can attach methods to:

type Vec4 [4]float32

While the code for a ray-sphere intersection isn’t that complex, it includes one vector subtraction and the computation of two dot products. Dot product is widely used in 3D graphics and machine learning. An imperative dot product in Go can be implemented as:

func DotProduct(v1, v2 []float32) float32 {

return v1[0]*v2[0] + v1[1]*v2[1] + v1[2]*v2[2] + v1[3]*v2[3]

}

From a code perspective, rather simple code. However, if we look at the compiled x86 assembly, we see that it does produce 11 assembly instructions:

Using objdump -d main > disassembly.txt and then finding the code (inlined inside std.IntersectSphere):

movss (%rdx), %xmm5

mulss %xmm1, %xmm5

movss 0x4(%rdx), %xmm6

mulss %xmm2, %xmm6

addss %xmm5, %xmm6

movss 0x8(%rdx), %xmm5

mulss %xmm3, %xmm5

addss %xmm6, %xmm5

movss 0xc(%rdx), %xmm6

mulss %xmm4, %xmm6

addss %xmm5, %xmm6

Pro-tip: On MacOS, the best way to see actual x86 assembly for a Go binary is to use

objdump -d <binary> > output-assembly.txt. Using-gcflags '-S'with the SIMD experiment does not produce the expected output for some of the SSE/AVX/AVX2 instructions.go tool pprof -S <binary>can also be useful as it outputs the Go source code along with the Go assembly, but note that Go assembly is not always 1:1 with the underlying x86 (or ARM) assembly instructions that will be executed by the CPU. Also, it is sometimes a good idea to tell the Go compiler to disable inlining and optimizations usinggo build -gcflags '-N -l'. This makes it somewhat easier to find assembly for a particular piece of code otherwise inlined by the compiler.

Dot product is a typical candidate for SIMD acceleration since one effectively wants to perform the same multiply operation element-wise and then add the results together, One can replace v1[0]*v2[0] + v1[1]*v2[1] + v1[2]*v2[2] + v1[3]*v2[3] with a fused multiply-add + two horizontal adds that operates on the two vectors element-wise. In theory, this should provide a performance boost since the CPU can do all 4 multiplications in a single instruction.

The code for a Go SIMD-acccelerated Dot Product can be varied somewhat depending on how the two input vectors are represented (slices, arrays, pointer to arrays etc.) but for the plain array example, it’s quite straightforward:

func DotProductSIMDArray(v1, v2 [4]float32) float32 {

r1 := simd.LoadFloat32x4(&v1) // [2,3,4,5]

r2 := simd.LoadFloat32x4(&v2) // [3,4,5,6]

sumdst := simd.Float32x4{} // Used to store intermediate results

sumdst = r1.MulAdd(r2, sumdst) // => [6,12,20,30]

sumdst = sumdst.AddPairs(sumdst) // => [18,50,18,50]

sumdst = sumdst.AddPairs(sumdst) // => [68,68,68,68]

return sumdst.GetElem(zero) // scalar 68

}

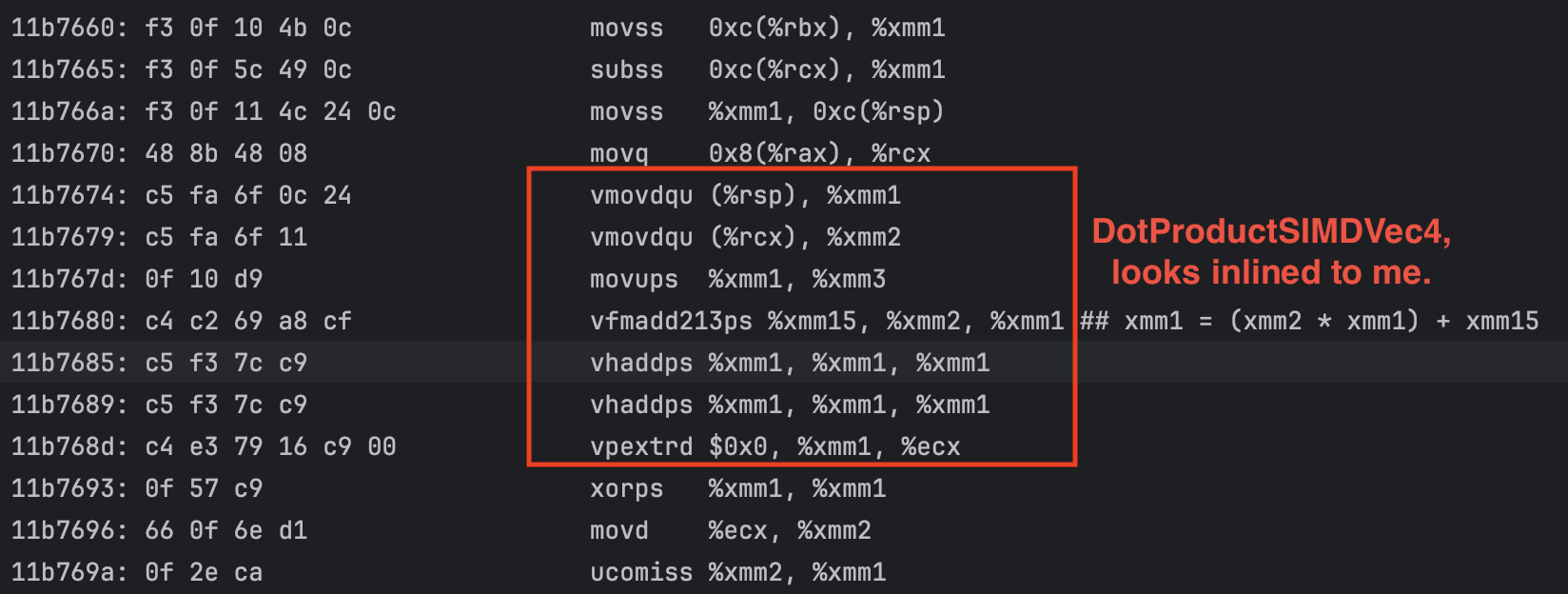

Example input vectors and intermediate results are written as comments. The MulAdd call (VFMADD213PS) effectively performs all four element-wise multiplications in one Go and stores the result in a 128-bit XMM register represented by the name sumdst. The two horizontal adds (VHADDPS) are performed which puts the final result in all four elements, where GetElem(0) (VPEXTRD) extracts and return the result.

The x86 assembly for the above:

movq 0x8(%rax), %rcx

vmovdqu (%rsp), %xmm1

vmovdqu (%rcx), %xmm2

movups %xmm1, %xmm3

vfmadd213ps %xmm15, %xmm2, %xmm1 ## xmm1 = (xmm2 * xmm1) + xmm15

vhaddps %xmm1, %xmm1, %xmm1

vhaddps %xmm1, %xmm1, %xmm1

vpextrd $0x0, %xmm1, %ecx

This results in 8 instructions at the cost of a lot more code complexity. So, which is faster? This is where it gets tricky.

We’ll benchmark this is in two ways:

go bench with the new for range b.Loop() on the dot product implementations.I have benchmarked no less than six different variants. BenchmarkDotSIMDSlice, BenchmarkDotSIMDArrayPtr and BenchmarkDotSIMDArray executes our own Go SIMD-based code, only varying how the input vectors are passed to the functions under test. BenchmarkDot is the plain-Go imperative version, while BenchmarkDotGoSIMD and BenchmarkDotAVX256a are more general purpose / varying length implementations linked from the Go SIMD proposal.

An example benchmark function:

func BenchmarkDotSIMDSlice(b *testing.B) {

v1 := []float32{2, 3, 4, 5}

v2 := []float32{3, 4, 5, 6}

for b.Loop() {

_ = DotProductSIMDSlice(v1, v2)

}

}

Some results from my 2019 MacBook Pro, sorted from fastest to slowest:

$ gotip test . -bench=BenchmarkDot -benchmem

cpu: Intel(R) Core(TM) i9-9880H CPU @ 2.30GHz

BenchmarkDotSIMDSlice-16 555698928 2.166 ns/op 0 B/op 0 allocs/op

BenchmarkDotSIMDArrayPtr-16 511945254 2.181 ns/op 0 B/op 0 allocs/op

BenchmarkDot-16 307990974 4.105 ns/op 0 B/op 0 allocs/op

BenchmarkDotGoSIMD-16 215681636 5.608 ns/op 0 B/op 0 allocs/op

BenchmarkDotAVX256a-16 189354781 6.244 ns/op 0 B/op 0 allocs/op

BenchmarkDotSIMDArray-16 145779706 8.251 ns/op 0 B/op 0 allocs/op

Both my SIMD variants passing the data to the DotProduct-functions using either slices or array pointers are almost twice as fast as the plain scalar Go version. The variant passing [4]float32 is very slow, probably due to copy-by-value for each iteration.

As a sidenote, processing 4 float32’s at a time actually only uses 128-bit wide registers. If we pack 8 float32’s into 256-bit wide registers, we can effectively perform two full 4x float32 dot products in a single call:

func DotProductSIMD2x4(v1, v2 []float32) (float32, float32) {

r1 := simd.LoadFloat32x8((*[8]float32)(v1)) // [2,3,4,5, 2,3,4,5]

r2 := simd.LoadFloat32x8((*[8]float32)(v2)) // [3,4,5,6, 3,4,5,7] <-- note final 7

sumdst := simd.Float32x8{}

sumdst = r1.MulAdd(r2, sumdst) // => [6,12,20,30, 6,12,20,35]

sumdst = sumdst.AddPairs(sumdst) // => [18,50,18,50, 18,55,18,55]

sumdst = sumdst.AddPairs(sumdst) // => [68,68,68,68, 73,73,73,73]

// GetElem cannot operate directly on 256-bit wide registers, in this case we instead

// store the results back to main memory and access them using plain Go code.

// It's significantly faster than using sumdst.GetLo().GetElem(0) and sumdst.GetHi().GetElem(0).

out := [8]float32{}

sumdst.Store(&out)

return out[0], out[4]

}

Results:

BenchmarkDotSIMD2x4-16 531969500 2.214 ns/op 0 B/op 0 allocs/op

BenchmarkDot2x4_2-16 177491343 6.829 ns/op 0 B/op 0 allocs/op

BenchmarkDot2x-16 155153811 7.802 ns/op 0 B/op 0 allocs/op

As seen, there is hardly any performance penalty for performing 2x4 element dot products using SIMD by stuffing four 4-element vectors into two [8]float32. There is a slight overhead writing the result back to main memory (probably CPU L1 cache) using sumdst.Store(&out) instead of calling GetElem, but since the declared out array doesn’t escape to the heap, it does not incur much of a performance penalty.

BenchmarkDot2x4_2-16 which uses the same 8-element float32 inputs with standard imperative scalar code is about 3x slower, while BenchmarkDot2x-16 which performs two separate calls to DotProduct(v1, v2 []float32) is another ns/op slower. Note that go test -bench with for range b.Loop() explicitly disables function inlining for contents in the for loop, BenchmarkDot2x-16 might be a tad bit faster with one less function call overhead.

No question about it, for a synthetic benchmark scenario, we see a substantial ~1.9x improvement for 4-element float32 dot products, and more than ~3x if taking advantage of 256-bit wide registers to perform two 4-element float32 dot products in a single call.

Let’s set the performance baseline again by benchmarking the IntersectSphere function in isolation. Internally, it will perform one or two dot products, as well as a vector subtraction and some rather ordinary if-statements and math operations.

The baseline benchmark declares a static ray (with origin and direction) and 6 spheres, where we know that at least one sphere will be intersected.

func BenchmarkIntersectSpheres(b *testing.B) {

spheres := StandardSpheres() // 6 spheres

ray := &Ray{

Orig: &Vec4{3.1, 4.1, 20.1, 0},

Dir: &Vec4{-0.47163668, 0.25912055, -0.8428614, 0},

}

for b.Loop() {

for _, s := range spheres {

_, _ = IntersectSphere(ray, s.Center, s.RadiusSquared)

}

}

}

The above call calls the ordinary IntersectSphere, the benchmark using SIMD is identical, except that it calls IntersectSphereSIMD instead.

$ gotip test . -bench=BenchmarkIntersect -test.benchtime=1s -benchmem

cpu: Intel(R) Core(TM) i9-9880H CPU @ 2.30GHz

BenchmarkIntersectSpheres-16 37628973 35.05 ns/op 0 B/op 0 allocs/op

BenchmarkIntersectSpheresSIMD-16 12480872 99.57 ns/op 0 B/op 0 allocs/op

What is going on? The SIMD version is almost three times slower!! The ray-sphere intersection code is identical except that the dot product calls go to their corresponding SIMD / non-SIMD implementations, which we in the previous section saw a 1.9x difference in favor of the SIMD given that we currently operate on 4-element vectors.

Is it inlining? By annotating both dot product functions with //go:noinline the plain solution clearly performs worse, while the SIMD one is basically unchanged:

BenchmarkIntersectSpheres-16 25536750 47.96 ns/op 0 B/op 0 allocs/op

BenchmarkIntersectSpheresSIMD-16 12693940 96.86 ns/op 0 B/op 0 allocs/op

This indicates that the Go compiler might not be inlining the calls to DotProductSIMDVec4 while the plain DotProduct version definitely is being inlined.

Taking a look at the generated assembly for the SIMD-enabled code path requires a few steps:

gotip test . -o testbinaryobjdump -d testbinary > disassembly-testbinary.txtdisassembly-testbinary.txt file for “simd-tracer/internal/app/std.IntersectSphereSIMD”As seen in the screenshot below where I’ve highlighted the SIMD-accelerated dot product, it does indeed seem to have been inlined.

So while the plain dot product suffers a severe performance penalty with inlining disabled, the SIMD one doesn’t seem to be affected at all by go:noline. However, the SIMD version is still about half as fast as the non-SIMD one.

A full render of the reference scene (seen in section 1, the Cornell box with 7 spheres with a lot of hard shadows) takes approx 76 ms using the SIMD code path, so the performance degradation is definitely not isolated to go test -bench runs.

In all honesty, I’ve spent perhaps an unreasonable amount of time trying to figure out why the SIMD-enabled ray-sphere intersection code is about 3x slower than the non-SIMD one, when plain benchmarking of the dot product functions in isolation clearly shows the SIMD-enabled code to be about twice as fast!

The natural first step is to use pprof to capture a CPU profile during a benchmark run in order to see where time is actually being spent.

Conveniently enough, one can capture a pprof CPU profile directly when running go test -bench by adding -cpuprofile <outfile>, such as:

$ gotip test . -bench=BenchmarkIntersectSpheresSIMD -test.benchtime=10s -o testbinary -cpuprofile simd1.pprof

$ gotip tool pprof simd1.pprof

(pprof)

Typing disasm std.* into the pprof console gives us source-code annotated timings on assembly-code level:

30ms 30ms 11b7674: VMOVDQU 0(SP), X1 ;simd-tracer/internal/app/std.IntersectSphereSIMD dot.go:103

2.47s 2.50s 11b7679: VMOVDQU 0(CX), X2 ;simd-tracer/internal/app/std.IntersectSphereSIMD dot.go:104

. . 11b767d: MOVUPS X1, X3 ;dot.go:106

400ms 400ms 11b7680: TESTL $0xcf, AL ;simd-tracer/internal/app/std.IntersectSphereSIMD dot.go:106

720ms 750ms 11b7685: JL 0x11b7652 ;simd-tracer/internal/app/std.IntersectSphereSIMD dot.go:107

790ms 820ms 11b7689: JL 0x11b7656 ;simd-tracer/internal/app/std.IntersectSphereSIMD dot.go:108

990ms 1s 11b768d: ? ;simd-tracer/internal/app/std.IntersectSphereSIMD dot.go:109

. . 11b768e: JRCXZ 0x11b7709 ;dot.go:109

. . 11b7690: ?

. . 11b7691: LEAVE

630ms 640ms 11b7692: ADDB CL, 0(DI) ;simd-tracer/internal/app/std.IntersectSphereSIMD dot.go:109

I must admit - I do not trust the output of disasm at this point. As previously stated, the Go assembly seems rather strange for the vectorized fused multiply add and horizontal add operations on lines 106-108 of the dot.go file above.

I was expecting VFMADD213PS and VHADDPS, but are seeing TESTL and JL (in x86 conditional jumps). Also, it seems quite strange that the first call to load our first four float32s into a SIMD register has taken 30ms, while the second one has a cumulative 2.5 seconds.

While we’re not seeing any heap allocations, my best guess is that something in my Go code or the generated assembly is resulting in some kind of CPU cache miss when IntersectSphereSIMD is being called. If data needs to be read from main memory instead of the CPU caches, the overhead can be as much as 100ns depending on CPU frequency and DRAM type. See latency numbers every programmer should know.

I believe that the next step may be to use a more low-level profiling tool.

I have yet to figure out how to perform profiling on x86 assembly code level on MacOS, or for that matter access hard CPU cache hit/miss metrics as possibly provided by the CPU’s hardware performance counters. I tried Instruments but were not able (possibly by my own fault) get any useful information out of it. I also took a look at dtrace, but was not able to figure out how to do the kind of low-level instrumentation I think is necessary.

I think my best bet may be to try my code on a Linux computer with perf.

Not happy to admit it, but I’m currently at a kind-of dead end here. The final x86 assembly obtained by objdump shows the expected SIMD assembly instructions, but for some reason, the performance when using SIMD for dot products in the ray-sphere intersection code is really bad.

I also tried running the code in this project on a Windows computer equipped with an AMD Ryzen 2600X CPU coupled with fast DRAM. However, while benchmark numbers differed somewhat, the SIMD code was still much slower than expected and did not deviate in any significant way from the figures seen on my Intel Mac.

That said, I’ve tried to modify my code in a number of different ways in order to possibly eliminate whatever bottleneck is causing the SIMD-enabled ray-sphere intersection to perform so miserably.

I have also spent a bit of time rewriting IntersectSphereSIMD to use SIMD code throughout rather than just for the dot products - for example loading input vectors into simd.Float32x4, computing the ray-origin to sphere center vector using vectorized subtraction and then reusing already declared simd.Float32x4 with manually inlined SIMD dot product code. Nevertheless, it still performs slightly worse than the plain Go code dot product. I’m aware that SIMD isn’t a silver bullet and that “data level parallelism” often requires the programmer to structure both code and data to properly take advantage of SIMD features. Perhaps my usage of SIMD for dot products results in an instruction level parallelism bottleneck to occur?

The article The Ubiquitous SSE vector class: Debunking a common myth is quite old, but does shed some possible light on the complexity of actually getting performance gains out of seemingly “simple” SIMD optimizations due to memory access, cache optimization and the overhead of loading/storing data to and from registers.

Well, this has been fun! Even though I’m just as stalled as I suspect my CPU is, I’ve learnt a good deal about low-level profiling, usage of the experimental Go SIMD API, a bit more about SIMD and assembly in general, and I also got to stretch some of my old ray-tracing legs.

I have not given up though - the truth and reason behind the surprisingly bad SIMD performance is out there, and I intend to pursue at least some kind of answer.

Also, it’d be really nice if the developers working on the Go SIMD API spends some time writing useful examples and guidelines on how to best use the new API, especially in regard to things I’ve encountered regarding unexpected performance and nitty-gritty details. And while not Go SIMD specific, some guide on “how to think in SIMD” might popularize the new API for Go developers (such as myself) not previously experienced in SIMD and/or low-level assembly.

In the next part of this series, I’ll try to implement ray-sphere intersections with a “SIMD mindset” from the get-go, rather than trying to utilize it for only certain parts such as dot products.

Until next time!